Coffee with Rashbam

☕ Time for an anachronistic coffee with the unfailingly bold, self-assured champion of peshat (contextual Torah commentary).

Wow, you guys. Thank you so much for the enthusiastic response, and welcome new subscribers! Shout out to Mosaic Magazine for featuring this newsletter. I’m just so happy you like hanging out with my best medieval friends as much as I do. Today we’re on the ground in Ramerupt (where? yeah, exactly; more below) for a one-on-one with Rashbam.

Questions? Thoughts? Feedback? HMU in the comments below. ⬇️

Getting to Know Rashbam

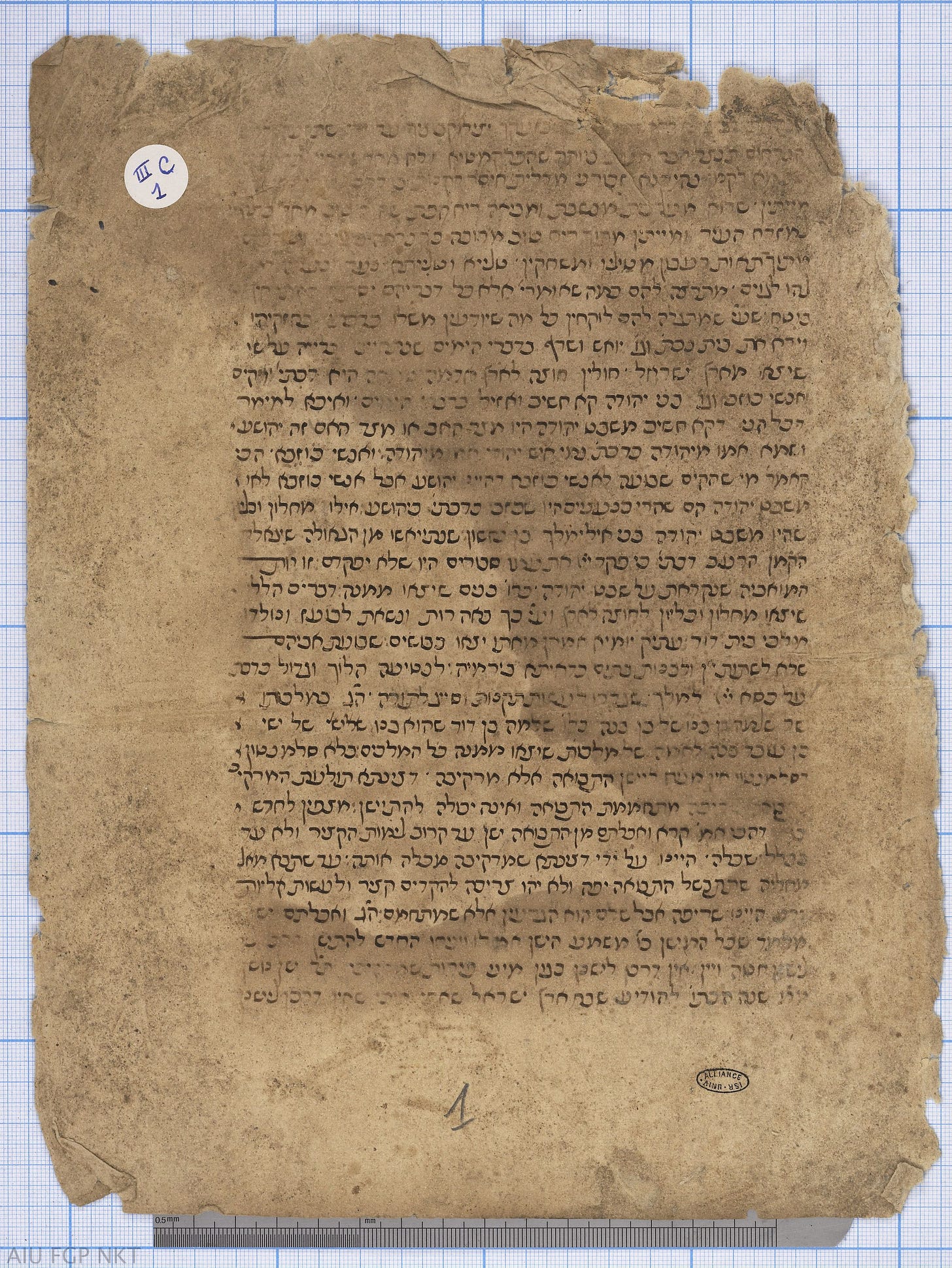

Rabbi Shmuel ben Meir, Rashbam to us, c. 1080/85-c. 1174, was one of Rashi’s famous grandsons as well as one of his illustrious pupils, known for his brazenly independent interpretation of Scripture. He’s less known, though unjustifiably so, for his prolix Talmud commentaries, which filled in lacunae left behind by Rashi. Rashbam’s commentary is printed as a supplement to Rashi’s unusually concise glosses on Chapter 10 of Pesachim (ערבי פסחים, the blockbuster perek that deals with the Passover Seder); also Rashbam’s is the commentary on Bava Batra from our page 29a until the end of the tractate.

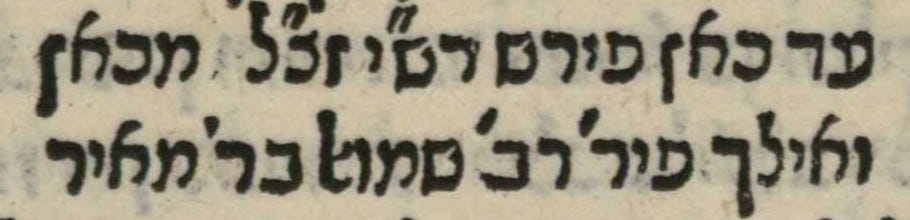

Here’s the note on Bava Batra 29a in the Bomberg Talmud, the first complete printing of the Bavli, printed in Venice between 1520-23: “Up to here explained Rashi, the righteous of blessed memory; from here onwards explained Rabbi Shmuel ben Meir [Rashbam].”

You can compare this to the version that ended up in the Vilna Shas, which reproduces the note in the Bomberg edition and also references the Pesaro edition of Gershom Soncino (which slightly predates the Bomberg), reading, “Here died Rashi of blessed memory.”

Okay, someday we’ll have a nice chat with Gershom Soncino about his press and why he self-censored the Pesaro tractates and what Daniel Bomberg totally ripped off from him, but now back to our regularly-scheduled Rashbam.

It’s been argued that living in the shadow of Rashi, not to mention that of his less-prickly, overachiever younger brother Rabbenu Tam, laid upon Rashbam a burdensome anxiety of influence: that it’s this that impelled him towards staking a claim of his own, or what we moderns would term originality. It couldn't have been otherwise, but I don't see Rashbam's personality as dominated by his grandfather’s legacy; he’s nothing if not self-possessed. And he’s got good reason to be. Unlike his contemporary Ibn Ezra, with his shifty secrecy and precarious lifestyle, Rashbam felt himself, rightly, at the very center of Ashkenazi high culture, his piety unimpeachable, his yichus (lineage) sterling, his beit midrash bustling.

Rashbam lived his whole life in the dusty Champagne town of Ramerupt. (If you thought Rashi’s Troyes had a small-town vibe, well, have you tried Ramerupt?) He was apparently there, as recent research indicates, because of exclusive rights granted to his brother by local officials. This meant that Rashbam had a potential vector of close interaction with local Christians, which is evidenced in his writings. Some scholars have argued that this is how Rashbam caught wind of the so-called Twelfth Century Renaissance, the outburst of knowledge production centered in the burgeoning church schools of Paris. Others have emphasized that it gave Rashbam familiarity with Christian readings of the Bible, which he answered explicitly with anti-Christological readings of his own. These Rashbam introduces with the phrase teshuvat ha-minim (תשובת המינים), “in response to the sectarians,” minim being a common medieval epithet for Christians.

On Rashbam’s “Why”

Among the landmark characteristics of medieval Ashkenazi intellectual culture is its messiness. It is very unlike the Western, post-Romantic (big-“R” Romantic) sense we have of closed authorship and bounded books with beginnings, middles, and ends. It is, however, quite a lot like that chaotic, postmodern place where we all spend so much of our time these days: the internet (with more piety and less irony, though; for irony you have to go to Sefarad). Just like we dip in and out, cut and paste, mash up authors in whatever way serves us, scroll endlessly and often randomly, so too did Ashkenazi Rishonim. This makes their works notoriously difficult to pin down, and their methods even harder.

Both of these difficulties are manifest in Rashbam’s legacy. Meaning, we don’t always know what of the stuff we have is really his work. For example, while we (probably) have most of Rashbam’s Torah commentary, it is known that he wrote commentaries on most of Nach (the Prophets and Writings) as well. There is fierce scholarly debate about whether and which rediscovered commentaries, for instance on Iyov (Job), are to be attributed to Rashbam. There is also the messy legacy of the Tosafot, our printed versions of which preserve relatively little of what Rashbam probably contributed.

But in a few rare moments, Rashbam reveals to us a bit of himself and his “why”:

והראשונים מתוך חסידותם נתעסקו לנטות אחרי הדרשות שהן עיקר ומתוך כך לא הורגלו בעומק פשוטו של מקרא. ...וגם רבינו שלמה אבי אמי מאיר עיני גולה שפירש תורה נביאים וכתובים, נתן לב לפרש פשוטו של מקרא. ואף אני שמואל ב"ר מאיר חתנו זצ"ל נתווכחתי עמו ולפניו והודה לי שאילו היה לו פנאי, היה צריך לעשות פירושים אחרים לפי הפשטות המתחדשים בכל יום. ועתה יראו המשכילים מה שפירשו הראשונים.

The early commentators, on account of their great piety, were occupied with leaning towards the expansive interpretations (derashot) that are the essence, and because of this they were not accustomed to the depths of the peshat of Scripture…Even our teacher Shlomo [Rashi], the father of my mother, illuminator of the eyes of the exiled—I argued with him and before him and he admitted to me that if he had the time, he would need to make different explanations according to the peshat approaches that are being innovated every day.

Rashbam declares his commitment to a new, deep way of understanding Torah, a way that he believed wholeheartedly would lead to greater wisdom and a closer relationship with the Source of all wisdom.

But what, exactly, did Rashbam mean by peshat? And why would it make Rashi want to rewrite his commentaries, had he but world enough and time?

Give It To Me Straight

Peshat is such a tricky word. The judicious, if none too brave, policy is to leave it untranslated. The word pashut in both rabbinic and modern Hebrew means “simple.” The Aramaic cognate, used as a favorite throw-down in Talmudic lingo, means “It’s obvious [eye roll].” But the root פ-ש-ט has a wider semantic range than that, meaning primarily “to spread out, to extend” (hence the modern Hebrew pashat, “take off,” as in clothing, and mitpashet, “to spread",” as in rumors), from which the meaning of “flat, plain, simple” arises secondarily. It wouldn’t be fair to describe peshat as merely the plain or simple meaning of the text, which readers, even those from the same time and place, will not naturally agree upon. Nor does it work to call it “literal,” given that metaphor is sometimes quite a lot “simpler” than literalism.

I prefer the admittedly cumbersome phrase “contextual reading” to stand in for peshat in English. The idea is that a peshat reading considers a verse as part of a text that is both local (you pay attention to the exact words in front of you) and synthetic (you pay attention to the narrative structure in which it appears). It is the New Criticism of the Middle Ages, a form of interpretation that eschews outside information in favor of looking closely and rationalistically at the specifics of words before you. (So no gematria, no aural wordplay, no reading-between-the-lines.) Here we can see what Rashi started—insisting on careful attention to the local verse and its positioning in the narrative—but didn’t finish. That job was to be his grandson’s.

And yet, it wasn’t just lip service that Rashbam paid to the primacy of Midrash and Gemara. He meant it, as his voluminous halachic work amply demonstrates. Rashbam deferred to rabbinic tradition even as he confidently declared that his peshat was the correct reading. This is an unresolved tension for us, but it wasn’t to Rashbam. He felt that the peshat was the deepest, most integral understanding of the text, and that the imprimatur for such a reading came from Chazal themselves, who emphasized that “a verse never departs from its peshat” (אין מקרא יוצא מידי פשוטו).

The Controversial Comment to Bereshit 1:5 (and its Afterlives)

To get a sense of how peshat works for Rashbam, as well as the complicated textual history involved, his controversial comment on Bereshit 1:5 offers a prime example:

ויהי ערב ויהי בקר - אין כתיב כאן ויהי לילה ויהי יום, אלא ויהי ערב, שהעריב יום ראשון ושיקע האור, ויהי בוקר, בוקרו של לילה, שעלה עמוד השחר, הרי הושלם יום א' מן השישה ימים שאמר הקב"ה בעשרת הדברות, ואח"כ התחיל יום שני, ויאמר אלקים יהי רקיע. ולא בא הכתוב לומר שהערב והבקר יום אחד הם, כי לא הוצרכנו לפרש אלא היאך היו ששה ימים, שהבקיר יום ונגמרה הלילה, הרי נגמר יום אחד והתחיל יום שני.

It is not written here “there was night and there was morning,” but rather “there was evening,” because the first day turned to evening and the light faded, and then it was morning, the morning of that night. When the first rays of light came up, it was then that the first day was completed of the six days [of creation] which the Holy One, blessed be He, mentioned in the Ten Commandments. After this began the second day, upon which G-d said, “Let there be a firmament.” The Torah doesn’t mean to say that the evening followed by the morning were one day, but rather comes to explain how there were six days: the the day dawned and ended at the completion of the night, and it was then [the next morning] that one day ended and the other began.

Rashbam on Bereshit 1:5

No, you’re not imagining things. Rashbam really just said that the source for the halachic beginning of day is not the way the very first day of creation is described in the Torah. Rather, the peshat of Bereshit 1:5 describes the day as starting in the morning with the rising of the sun and stretching on through the night until the following morning. To be sure, Rashbam did not in any way contest the halachic definition of a day as beginning at nightfall. He went on marking the start of Shabbat at sunset on Friday, no doubt. But he did insist that this was not the meaning of this particular verse of the Torah.

If this seems radical, well, it’s been subject to debate, complaint, and censorship throughout the ages. Recently, a major Jewish publisher omitted the comment based on the rationale that the beginning of Rashbam’s Torah commentary is only attested in a single manuscript copy which didn’t surface until the 19th century. (Rabbis and scholars objected.) This in itself raises several important points: first, how powerful Rashbam’s read was; second, how tenuous the survival of his work was; and also how common this fate was for Rishonim—their genius remembered on the basis of a single, hand-written book, or maybe a handful. Five to seven is a “robust” number of manuscripts for a work from the Jewish Middle Ages.

Rashbam reminds us, finally, for all that we value originality, we haven't cornered the market on it: in fact, we are sometimes bested by the boldness of our forefathers. We need not shy away from what Rashbam called “the peshat approaches that are being innovated every day.”

Rashbam Reads

Someone actually did write the book on Rashbam: Elazar Touitou, Exegesis in Perpetual Motion: Studies in the Pentateuchal Commentary of Rabbi Samuel ben Meir [הפשטות המתחדשים בכל יום: עיונים בפירושו של רשב”ם לתורה] (Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press, 2003). Well, it’s about Rashbam as a Torah commentator, but it’s still the one. Highly recommended if you read Hebrew; you can buy a copy or the digital version at the link from BIU Press. If you’re not a Hebrew reader, the next one is for you:

I realize my normal meter on what constitutes a fun read is, um, not well calibrated, but I think this is an approachable (if, yeah, still academic) piece that lays out the basic problems and approaches to understanding Rashbam’s work (and it’s freely available on Academia.edu): Jason Kalman, “When What You See Is Not What You Get: Rashbam’s Commentary on Job and the Methodological Challenges of Studying Northern French Jewish Biblical Exegesis,” Religion Compass 2, no. 5 (September 2008): 844–61 [DOI | Academia.edu].

Quicker read: Rabbi Alex Israel explores how the two contemporaries, Rashbam and Ibn Ezra, differed in their take on tefillin—and what it means for their understanding of the Oral Torah. I think this is a great test case because they’re both devoted to peshat, but one from an Ashkenazi perspective and the other from a Sefardi approach.

Question for you: Would you like footnotes to the newsletter? I put them in experimentally but then decided that they kill the vibe and took them out. Lmk!

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

If you’re the kind of person who delights in Jewish calendar math (represent), this one’s for you. Forgot how much a hin of oil is? Need to sort out Gematria possibilities? (I won’t tell Rashbam, don’t worry.) TorahCalc is here for you.

Rashbam on Twitter

ICYMI - the Rashbam thread:

Next Time

Okay, you might have seen this coming, but we’re gonna be in Ramerupt for a while. Next up: Rabbenu Tam.

This is a fine introduction. An excellent translation and commentary of Rashbam on Torah is by Martin Lockshin.

https://www.amazon.com/Books-Martin-I-Lockshin/s?rh=n%3A283155%2Cp_27%3AMartin+I.+Lockshin