The Geonic Yeshivot and the Exilarchate

🕍 Today we explore the functioning of the great academies of Bavel and of the office of the Reish Galuta (Exilarch), principally based on the account of R. Natan ha-Bavli.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. After a short summer break, we’re back to exploring to world of the Geonim, who presided over central Jewish institutions of the early medieval period in the Islamicate world.

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here (and an archive of all audio editions here.)

In this Issue:

More on Natan ha-Bavli’s Account

In introducing the Geonic period, I wrote a bit about the account of one R. Natan ben Yitzchak ha-Kohen ha-Bavli. Since we’re digging deeper into it today, I’ll add a number of details. Natan ha-Bavli’s account is an important primary source about the yeshivot of Bavel as he witnessed them, probably around 930. The account comes to about ten printed pages, so it’s substantial, though much shorter than the letter of Rav Sherira Gaon, which is really a short book. A lot of what we know and imagine about these great academies comes from the imagery and sense of venerability conveyed by R. Natan.

However, it’s important to note two critical limitations to the account. First, R. Natan, as we’ve noted, was almost certainly not a true insider to the yeshivot, but a layperson. (Robert Brody suggests that the “rabbi” attached to his name is an honorific, rather than an indicator of his communal role as a posek (halachic decisor), as is the case with many premodern learned Jews to whom the title has been respectfully appended.) From other sources, we know that he occasionally makes mistakes in the details he reports. In addition, he emphasizes the higher standing of the yeshiva of Sura in comparison to Pumbedita, while we know that in his period, Sura was in dire straits and at times shuttered. More importantly, Natan ha-Bavli often speaks in general terms when we should understand him as speaking to a particular time and place. We need to be careful about retrojecting a tenth-century reality onto earlier Geonic times. In general, however, R. Natan’s account remains a vital source for the functioning of the great yeshivot in their heyday in Baghdad.

R. Natan’s moniker “ha-Bavli” (“the Babylonian”) already tells us that he is located outside of Babylonia (a.k.a. Muslim Iraq) at the time he is writing. Back in Bavel, everyone is “Bavli” and thus not distinguished by this characteristic. It seems that, being from the East, R. Natan was tasked with addressing a curious situation: an erstwhile exilarch (Reish Galuta), Mar Ukva (or Uqba), had been deposed and forced into exile due to a dispute that arose between him and the Gaon of Pumbedita in the years 909-916. The controversy involved, interestingly, the rights to the monies from the reshut (financial district) of Khorasan, a region of Persia. Not long after this, the decline in revenues from reshuyot due to upstart communities would create dire situations for both Babylonian academies. Mar Ukva found a new home in Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia), arousing questions in his new community, which, despite his checkered past, welcomed him with the dignity befitting his former office. Having found his way to Ifriqiya, R. Natan, being from back East, was the perfect informant about Mar Ukva’s backstory.

The account produced by R. Natan was almost certainly written originally in Judeo-Arabic, the lingua franca of the Jewish community though not the scholarly language of Geonic insiders. Fragments of the lost original have turned up in the Cairo geniza. The more complete Hebrew version we have is thus a translation, of unknown provenance. The Hebrew version survived into modernity in one known copy, now lost. Fortunately, it was twice published before disappearing, including, most recently, in 1895. As we have it, the first section deals with controversies between the exilarch and the Geonim, first Mar Ukva’s and then the famously thorny affair that embroiled R. Saadia Gaon and the Reish Galuta David ben Zakkai. (Of course we’ll get into that in an upcoming newsletter.) The second section covers the functioning of the exilarchate and the yeshivot, which is of tremendous interest, in spite of the limitations we noted above. It’s this second section that we’ll unpack here.

The Functioning of the Exilarchate

The larger portion of the second section of R. Natan’s account is devoted not to the academies but to the exilarch’s role, especially the manner in which he is selected and installed. The institution of official representation of a minority religious community was a feature of Persian government continued by Muslim rulers. We also know of, for example, the Catholicos, who was the official representative of the Nestorian Christian community to the caliphate. Extant Nestorian documentation corroborates the sense in R. Natan’s account that there was an internal, communal process for selecting this representative. In the case of the Reish Galuta or Jewish exilarch, candidates were chosen from an elite cadre of families who claimed Davidic descent through King Yehoyachin, who had been exiled to Babylonia in Biblical times. As we’ll see with the leading positions in the academy, this made the succession largely, though not simply, hereditary, a feature of Babylonian Jewish society.

In R. Natan’s telling, the installation of the chosen exilarch takes place over several days, beginning with the gathering of prominent community members in the home of a leading family, to whom the honor of hosting is conferred. The Thursday prior, the community gathers at the synagogue where a shofar is sounded and the candidate is blessed, given a ceremonial form of semicha (laying-on of hands), and showered with expensive gifts, including regalia to wear on Shabbat. The incoming exilarch is tasked with hosting a lavish banquet following the gathering: “He toils in putting on a feast on that day…including many types of food and drink and delicacies, such as variety of sweets.” The ceremony culminates during a heightened Shabbat service in which the exilarch is presented, honored, and delivers a special sermon.

Next, the procedure for the exilarch’s audience with the “king,” meaning the ruler, in this case caliph, is described. Here too formality rules the day: in a scripted exchange, the exilarch requests an audience from the caliph’s ministers, who formally grant it, upon which the exilarch presents them with gifts. The exilarch shows great deference to the caliph, waiting to be indirectly signaled to arise and then to sit, but R. Natan also emphasizes the mutual cordiality between the two officials. He also mentions that the caliph would issue in writing the negotiated agreement for the exilarch to take.

The Functioning of the Academies

Of great interest to anyone who’s participated in the long tradition of yeshiva learning, the last part of R. Natan’s account describes how the great yeshivot functioned in his day. R. Natan apparently attended a Kallah month, and his description of what he saw, though including some outsider’s misunderstandings, can be taken as an eyewitness account of the first half of the tenth century. Twice a year, once in the winter, in the month of Adar, and once in the summer, during the month of Elul, yeshiva students would travel from their hometowns to their yeshiva for a convocation. There were two types of students, in R. Natan’s telling: a group to whom a given tractate was assigned at the end of one convocation to be learned for the next one, and another group who had the prerogative to select their own material for study. Either one or both groups received stipends (it’s not entirely clear from the account or the other source material).

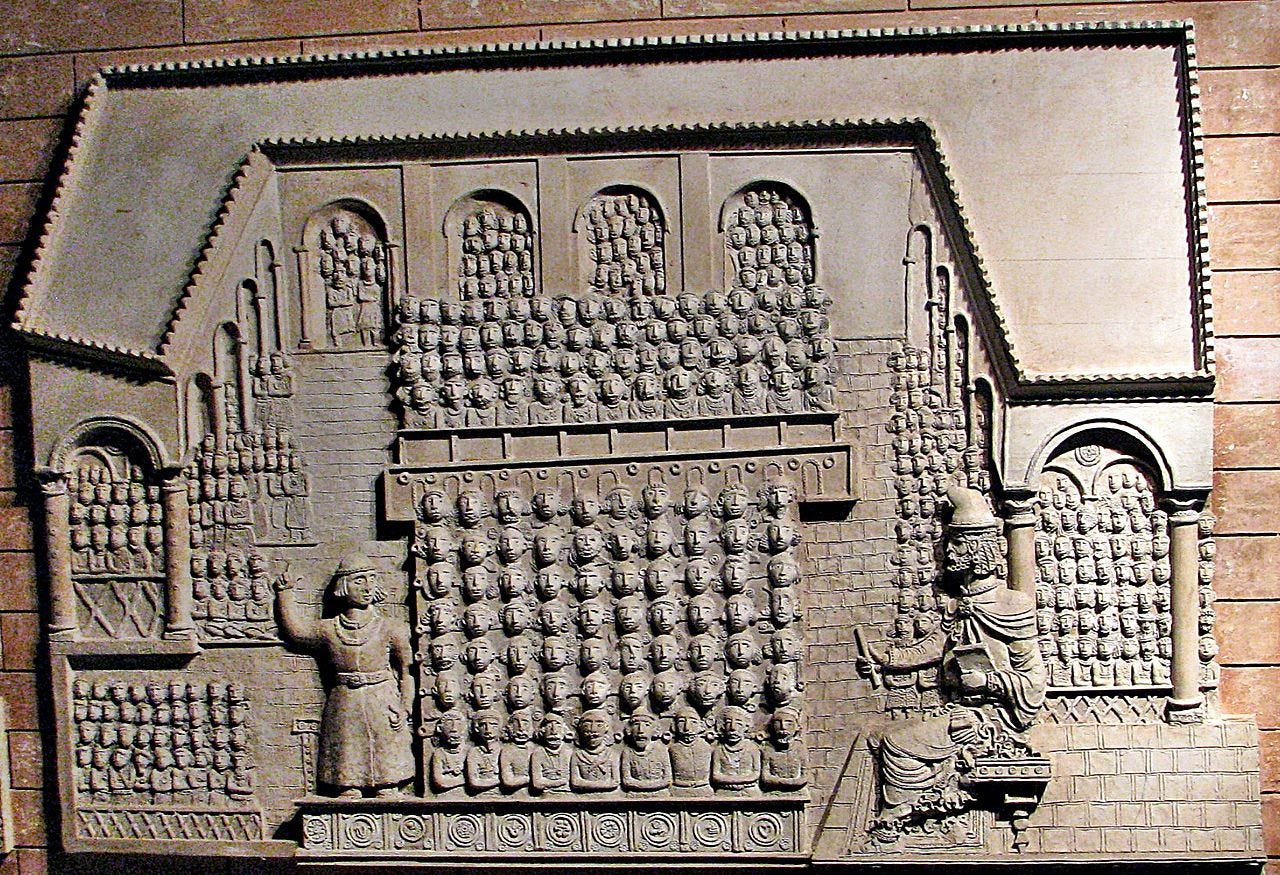

The structure of the yeshiva was rigidly hierarchical, with the Gaon presiding as head and beneath him, ten heads of rows, seven of whom were Rashei Kallah (“head of convocation”) and three of whom were known as Chaverim. Each of the seven Rashei Kallah presided over a row of ten Alufim, which constituted a Sanhedrin of seventy. Behind them, in open seating, were the four hundred students.

The daily activities of the Kallah term involved clarifying the material learned in advance and responding to queries received from far and wide, in which all members of the yeshiva were involved. Students would discuss their questions and disagreements, which would be explained and resolved by the Gaon. After his explanation, a member of the first row would stand up and repeat the answer. The procedure for answering queries (she’elot) is described by R. Natan as follows:

וכך היה מנהגם בתשובת השאלות בכל יום מהחודש אדר מוציא אליהם כל השאלות שהגיעו אליו ונותןלהם רשות שישיבו תשובה עליהם והם מכבדין אותו ואומרין לו לא נשיב בפניך עד שהוא תוקף בהם ואז מדברים כל אחד ואחד לפי דעתו לפי חכמתו ומקשין ומפרקין ונושאין ונותנין בכח דבר ודבר ומעיינין יפה יפה. וראש ישיבה שומע את דבריהם ומבין כל מה שאומרין ומקשין זה לזה ועומד ומעיין בדבריהם עד שיתברר לו האמת ומיד יצוה לסופר להשיב ולכתוב. וכך היה מנהגם לעשות בכל יום ויום עד שמשיבין תשובת כל השאלות שבאו להם השנה מקהלות ישראל ובתכלית החודש יקראו התשובות והשאלות במעמד כל החבורה כלה וחותם עליהם ראש ישיבה ואחר כך שולחין אותם לבעליהן ואז מחלק הממון עליהם.

This was their practice with regards to responding to the queries: on each day of the month of Adar, he [the Gaon] would bring out all the queries that had arrived addressed to him and would grant them [the assembled members of the yeshiva] permission to render responses to them. They would show respect to him, saying, “We shall not reply before you,” until he firmly enjoins them. Then, each and every one speaks according to his opinion and his knowledge, raising difficulties and taking them apart, discussing each topic and investigating deeply. The Rosh Yeshiva hears all they are saying and understands their discourse with all the difficulties raised. He stands and examines their words until he discerns the truth, upon which he immediately instructs the scribe to reply in writing. Thus was their practice to do on each day until they responded to all the queries that came to them that year from the Jewish communities. At the end of the month, they would read out all the answers and their respective queries at an assembly of all the members, after which the Rosh Yeshiva would sign them and afterwards send them to the questioners, and then distribute the monies.

Neubauer, ed., Mediaeval Jewish Chronicles, vol. 2, p. 88.

During each of the four Shabbatot of the Kallah month, the students would be examined by the Gaon for evidence of their mastery of the material: knowing it correctly, understanding it aptly, and being able to draw halachic conclusions. The verb R. Natan continually uses for this activity is garas, which seems to reflect an oral learning culture. The student’s stipend depended upon his performance in these examinations, and R. Natan is explicit in citing the harsh admonitions received by those who proved not up to snuff. The stuff of student nightmares!

Reads & Resources

You can find Chibur Natan ha-Bavli in Adolphe Neubauer’s Mediaeval Jewish Chronicles, vol. 2, pp. 77-88, available here (it’s under the heading “Seder Olam Zuta”).

There is much scholarly literature on R. Natan’s account and period, much of it in Hebrew, hard-to-find periodicals, or specialty volumes. A masterful synthetic and analytical treatment is in Robert Brody’s The Geonim of Babylonia and the Making of Medieval Jewish Culture, which is difficult to track down, alas. There is not enough accessible writing on this period! I hope the first chapter of my book will help.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective. If you’d prefer to make a one-time donation in any amount, you can do that easily through my page at Ko-fi. Thank you so much.