Coffee with Menachem ha-Meiri

☕ His prolix work languished in manuscript for centuries, but today, happily, we have Meiri's unique contributions to guide us ably through the Talmud.

It’s another medieval Tuesday, friends! This week we’re in Perpignan, the jewel of the French Pyrenees and an important medieval Jewish community, getting to know R. Menachem ha-Meiri. His story is tinged with sadness but don’t worry, there’s a happy ending. And the middle? It’s just so good.

In this issue:

A Provençal Life

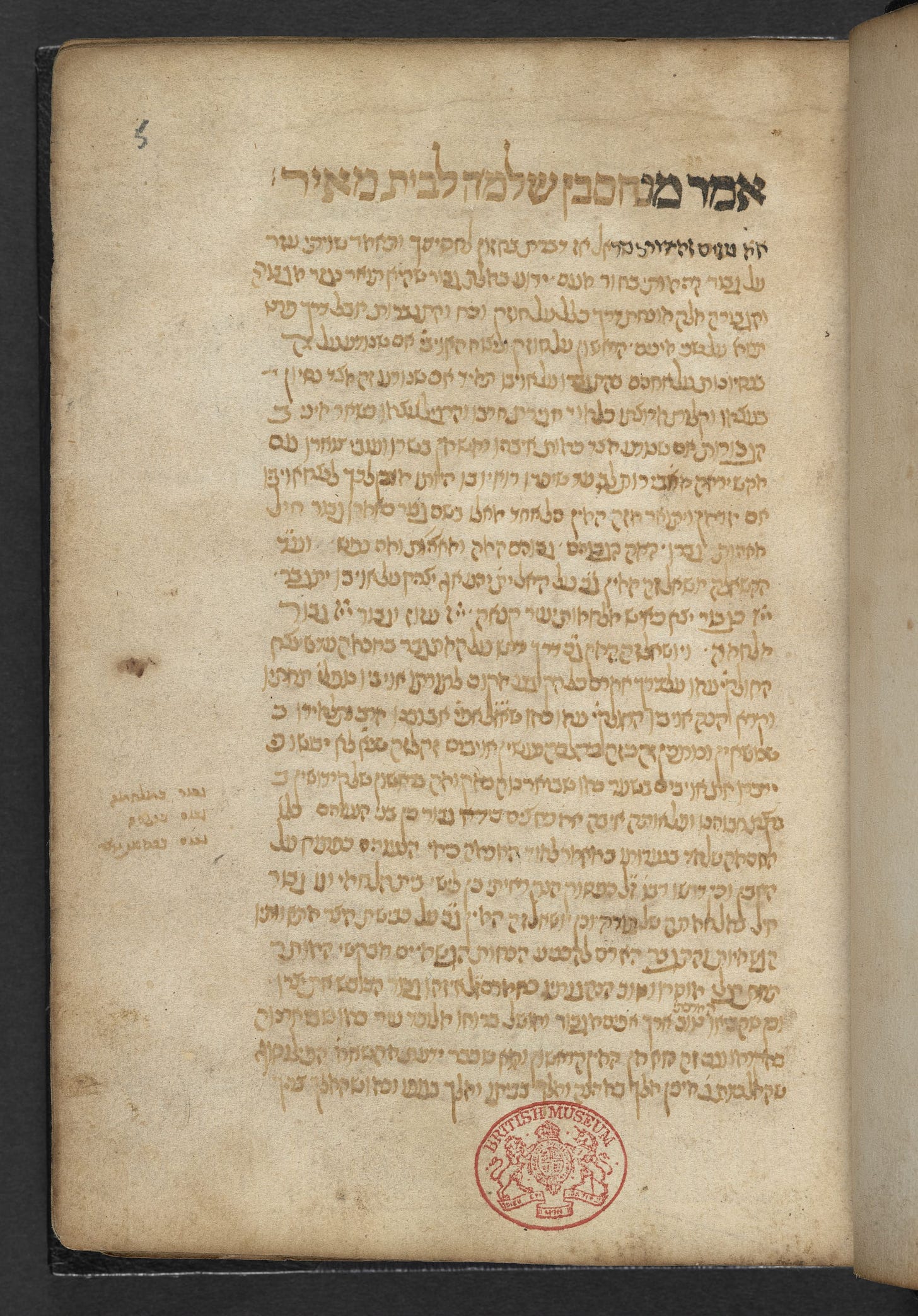

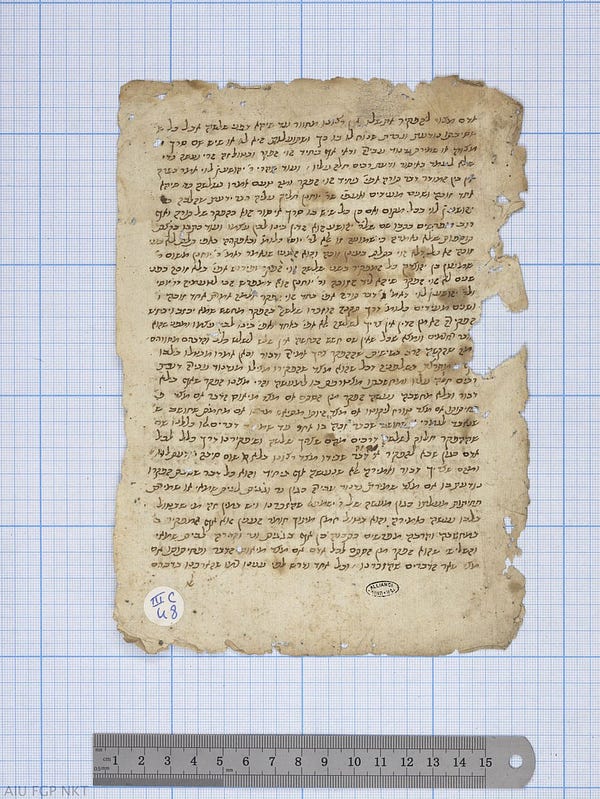

In the introduction to Kiryat Sefer, his book on the laws of writing a Torah scroll, R. Menachem ben Shlomo ha-Meiri records a series of travails that afflicted him and his fellow Provençal Jews. These have sometimes been taken literally, though the belletristic melitza style he employs, de rigueur for educated men of the region, elides the nature of the personal tragedy. What else we do know of his personal life paints a picture of privilege.

Known as Don Vidal Solomon (“don” is an honorific title) in archival documents, these show him to have been a wealthy moneylender. His family was from Carcassonne and Narbonne, centers of Provençal Jewish life. From there they migrated to Perpignan, a thriving city on the French side of the Pyrenees, Meiri’s hometown. Not directly subject to the French Crown, Perpignan became a haven for Provençal Jews fleeing the 1306 general order of expulsion, which devastated Provençal Jewish culture. This meant that ha-Meiri was spared from that upheaval, though perhaps not the general instability of the period.

In his introduction Pirkei Avot, known as Seder ha-Kabbalah, Meiri gives a detailed account of Torah scholarship down to his own day. From there we know a few salient facts about ha-Meiri’s life. We know he completed Seder ha-Kabbalah in the year 1300, when he was fifty-one years old. This gives us a birthdate of 1249; his year of death is surmised to be c. 1315. He gives as his primary teacher R. Reuven ben Chaim, a student of a student of Raavad’s—quite a prestigious scholarly lineage.

A Centrist Radical?

Despite his entirely aristocratic and conventional-for-Provence upbringing, Meiri has something of the air of a radical. This is due to several factors. One is his involvement in the Maimonidean controversies of the early fourteenth century, in which he took a public stance in favor of philosophical study, contra the Rashba. Another is his unusual, “progressive” halachic positions that presage issues we’re grappling with many centuries later. And finally, we have the fact that most of his works were not printed until late in history, many only in the 20th century, meaning that his halacha “fell out” of the chain of tradition. We’ll unpack these factors one at a time.

During the latest iteration of the controversies in response to Rambam’s works, debate occurred literally, in synagogues on Shabbat afternoons, as well as in personal and public letters.1 Meiri put his views to writing in a series of letters later publicized under the title Choshen ha-Mishpat. Since he opposes the lobbying efforts of Rashba to pass a ban of excommunication against the underage study of philosophy, Meiri is often classed on the “rationalist” side of the debate. But Maimonideanism—the integration of science and human reason with traditional thought—was an accepted tradition in Provence in particular. Meiri is consistently a proponent of the integrity of Provençal custom; he wrote a book, Magen Avot, defending Provençal halachic tradition.

Ha-Meiri does espouse notably idiosyncratic halachic opinions among his fellow RIshonim. One is his view that Christians should not be accounted idolators. This idea occurs in many places in his Talmud commentary. For example, he describes temples of idolatry as:

בתי עובדי האלילים ושאר בעלי האמונות הקדומות שלא היו גדורות בדרכי הדתות והם הנזכרים בתלמוד תמיד בלשון אומות העולם.

“The buildings of idol worshippers and other types of ancient beliefs of those who were not constrained by the ways of religion (gedurot be-darchei ha-datot), and which are always mentioned in the Talmud in the language of ‘nations of the world’”

In other words, the common language of idolatry in the Talmud should not be seen as applying to contemporaries who are constrained by a form of religion.

Another notable position Meiri takes is his positive view of women. For instance, in discussing the third and fourth blessings of the Sheva Brachot said at a wedding feast, which refer to adam, a word that can be understood as Adam, a specific, first man, or generically as “man” or “human.” On this Meiri writes:

ובאו אחר כך שתי יצירות אחת לעיקר בריאת אדם ואחת כנגד חוה והוא האחרון ואדם שבחתימתה ר"ל אשה כאמרו כתפארת אדם כל נפש אדם

“Following this [the second blessing] there are two creations, one about the essence of the creation of Adam and the other relating to the creation of Chava (Eve), which is at the end, and the adam that is at its conclusion, what I mean to say is, this [relates to] Woman, as it is said, ‘the beauty of man,’2 [meaning] any human soul.

There are some precedents for such views in the thought of other Rishonim, notably in the Tosafot’s discussion of shituf (combining worship of G-d with that of lesser powers or intermediaries, such as saints). In addition, these and other views likely reflect lost Provençal traditions. If nothing else, they function like other instances of da’at yachid (an individual opinion) among Rishonim and are immensely valuable coming from a Torah scholar of the stature of Meiri.

Finally, we have the charge against Meiri of having fallen out of the chain of Masora. According to this argument, since Meiri wasn’t available to the Mechaber (author) of Shulchan Aruch, the legal code accepted by Klal Yisrael (the Jewish community as a whole) in the sixteenth century, his halachic views cannot now be relied upon. This is of course a much larger, completely fascinating issue. For now, I’ll refer to Shnayer Leiman’s point that the Chazon Ish, usually (and with good reason) credited with this view, himself uses equivocal language on the matter.3

Remember how I promised you a happy ending? Most of ha-Meiri's works, after laying in wait for centuries, have now seen the light of day, and are widely available. And they are amazing.

Welcome to Beit ha-Bechira

I think Meiri’s moderate Maimonidean nature is expressed in his masterpiece, the Beit ha-Bechira. The title alludes immediately to the Beit ha-Mikdash (Beit ha-Bechira is a term for the Jerusalem Temple), reflecting Meiri’s concern for the centrality of Talmud study and masora. The Talmud is the closest thing we’ve got to a Mikdash now, he says in effect. In his general introduction to the work, he lays out his case against “the opposition” (ha-mitnagdim), rationalists who would lay such learning aside for what they view as more relevant subjects. At the same time, the choice of title harkens to Rambam’s own choice to term the Temple laws Hilchot Beit ha-Bechira: Meiri places himself firmly in the proud Maimonidean tradition of Provence.

But most of all, Meiri’s orientation is captured in the actual technique of his commentary. This is yet another facet expressed by its title, bechira also meaning, simply, “selection.” As Meiri explains: “Herein are matters that have been selected without the admixture of difficulties, resolutions, and dialectics” (זה כולל דברים נבררים באין תערובת קושיא ותירוץ ומשא ומתן). His aim is to clarify, and he does so in clear, sparkling (if often lengthy) language.

What sets Meiri’s commentary apart is not only its clarity but its overviews and summaries. First, Meiri gives a thematic overview of each section of text, with attention to key concepts as well as meaning—the significance and purpose of the area of law. He also gives attention to the aggadata, the non-legal sections of Talmud. Second, he gives a chronological summary of discussions on the topic at hand, carefully parsing the Mishnah and comparing the Bavli to the Yerushalmi in many places. He then proceeds up to current discussions, ending with his own view. He is comprehensive and sophisticated without being labyrinthine and confusing.

Interestingly, ha-Meiri also wrote more conventional Chiddushim (“Insights”) on several tractates of the Talmud. These show him to be working both in an established tradition as well as developing his own, unique style.

Meiri Reads

Meiri has not been much translated into English, but most of the Hebrew is available on Sefaria or else on HebrewBooks.org. Ofeq, a scholarly imprint of Koren, has published beautiful editions of Seder ha-Kabbalah (sadly, it looks to be out of print) and the Commentary on Pirkei Avot. Feldheim has an English translation of the Commentary on Pirkei Avot.

Much of the scholarship on Meiri is also in Hebrew. The book on Meiri is Moshe Halbertal’s (Hebrew) בין תורה לחכמה.

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

The National Library of Israel’s piyut (liturgical poetry) website is a total treat. Available in English as well as Hebrew, it features the words, melodies, and histories of familiar and rare piyutim from all corners of the Jewish world. Not only is it great for research and real-life use, it features a customizable piyut radio that plays timely or randomized sung poems.

Meiri on Twitter

Next Coffee Date

Next week we’re meeting up with the Rosh, R. Asher ben Yechiel.

It’s often the letters that record these rancorous afternoons! I wrote about that here (fair warning, it’s an academic journal piece).

Kovetz Iggerot (Bnei Brak, 1956), vol. 2, p. 37 (no. 23).