Coffee with the Rosh

☕R. Asher ben Yechiel carried with him the Chasidut of his father and the Tosafot of his teacher, Maharam of Rothenburg, and transplanted it to faraway Sefarad, integrating power traditions.

Happy Purim! I may be only one-eighth Litvak but let me tell you, those genes are strong. Look under “dour” in the dictionary and there’s a picture of me. So no parody newsletter today, we’re here on serious Rosh business.

A major theme of the past several figures has been synthesis and integration. In Rosh, however, we have a direct tradent: a major rabbi who personally moves from Ashkenaz to Sefarad.

In this issue:

Into the Limelight

Rosh (c. 1250–1327) was born into an Ashkenazi world in full bloom. Having recovered somewhat from violent outbreaks during the First and Second Crusades, Franco-Germany had produced two robust spiritual-intellectual movements, the pietistic movement of Chasidei Ashkenaz, alongside the fertile Tosafist enterprise that produced reams of scholarship on the Talmud, as well as stand-alone halachic books and codes of law. The young Rosh was exposed to both of these intellectual modes. His father and first teacher was a student of R. Yehuda he-Chasid, among the most famed of Chasidei Ashkenaz. He then seems to have spent some time learning in Tzarfat (northern France) before settling in Cologne (Köln), with which he is often associated. However, Rosh made his way to Worms, becoming a leading student of the great Maharam of Rothenburg. Maharam, one of the last great Tosafists, passed to Rosh the wealth of his scholarship.

Sadly, the situation in Germany began to deteriorate not long after Rosh’s birth, compounded by the interregnum, when authority over German lands was in contest. (Periods of transition of power, and especially political uncertainty, generally spelled trouble for premodern people, and especially minorities such as Jews.) When Maharam attempted to flee to safety, he was arrested. Into the fray, Rosh was ineluctably thrust. His attempts to secure the release of his teacher, including a substantial pledge of his own money, show Rosh to be a wealthy and influential member of the elite by the time the limelight shone on him.

From Germany to Spain

Rosh learned well the lessons of Maharam’s political entanglements. Concomitant with that were a series of blood libels in Germany in the 1280s, including at Mainz, Munich, and Oberwesel, and then the outbreak of the Rindfleisch Massacres in 1298. Rindfleisch is a personal name—that of the instigator of a wave of violent popular backlash against resident Jews in central and south Germany. The perpetrators operated in the wake of royal distraction—in other words, without the consent, and largely against the interests of, the ruling powers—with strong representation of the rising middle class of burghers and knights. By the time the series of massacres was over, in the early years of the fourteenth century, close to a hundred and fifty Jewish communities were affected and many, many Jews had been murdered, brutalized, or forcibly converted to Christianity. Some of Rosh’s over a thousand surviving teshuvot reveal that he was one of the communal leaders tasked with dealing with the sensitive situations created by the mass violence.

Rosh subsequently made the very understandable decision to get out of Dodge. It seems, based on a fresh reading of the evidence, that he did not initially plan to immigrate to Spain. He first made his way, c. 1303, to French Crown lands, the Jewish communities of which he extolled, only to be stymied by the French general order of expulsion which came down in the summer of 1306. This impelled Rosh to immigrate further afield. Though fêted by the Rashba in Barcelona, he made his way to Toledo, where at least one of his sons had already settled. There, in Castile, fumbling in Arabic and ostensibly the local vernacular, Rosh rebuilt his life. And when I say rebuilt, I mean, became nothing less than a living legend.

A Pillar of Israel

In Toledo, Rosh became a dayan and the head of a flourishing yeshiva. His acculturation was bidirectional: even as he accustomed himself to local cultural conditions, he was an active force transplanting his Ashkenazi heritage to Sefardi soil. Thus, for example, he displayed typical Ashkenazi disinterest in philosophy and summarily rallied to the cause of the ban against its study—while also encouraging one R. Yitzchak Israeli to write his scientific work, Yesod Olam.1

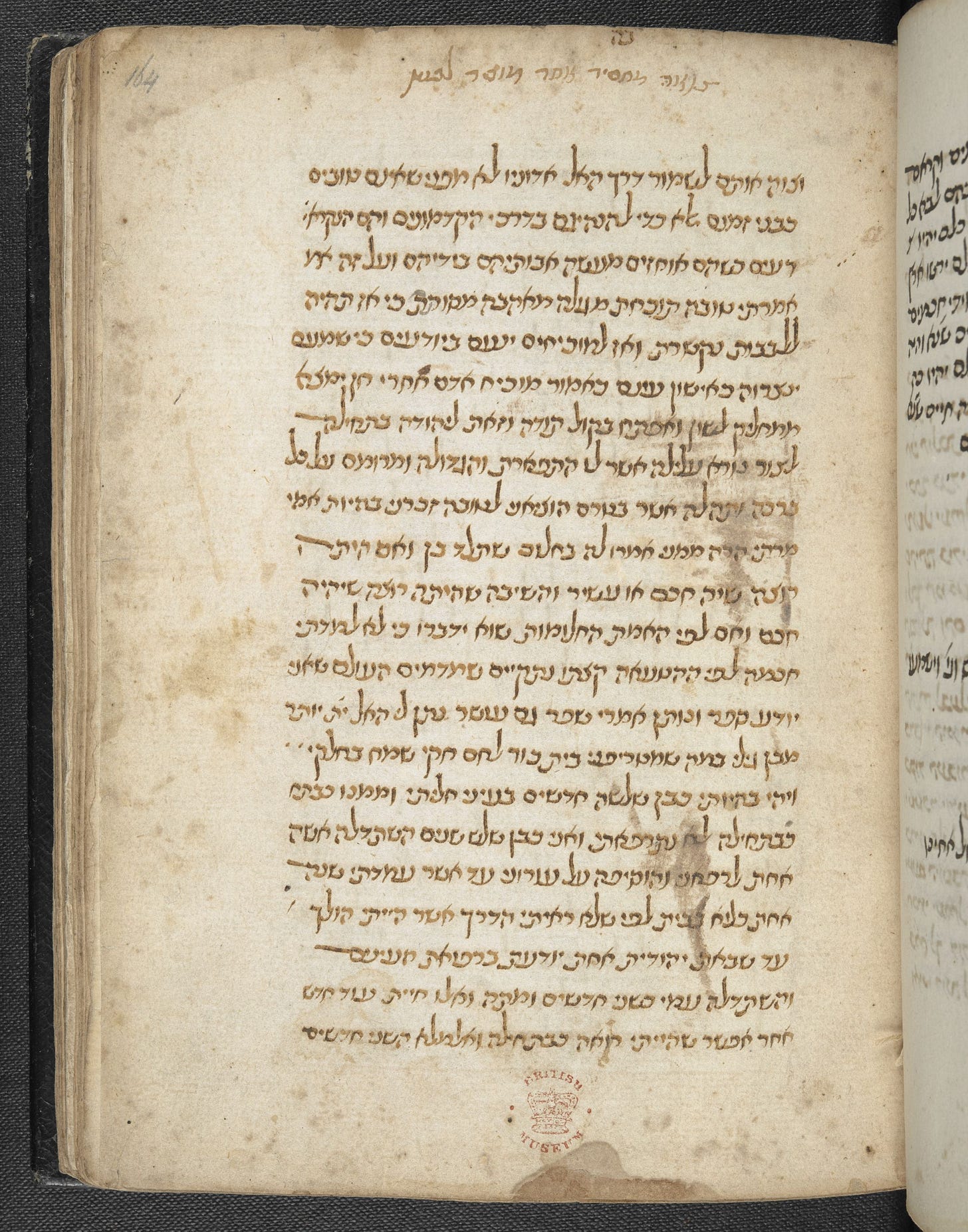

Today, the version of Tosafot to the Talmud known as Tosafot ha-Rosh preserve a recension redacted in the French city of Sens (שנץ) and used in the beit midrash of the Maharam of Rothenburg. These became the predominant form in which Tosafot were directly studied in Sefarad. In addition to this bequest, Rosh produced a comprehensive commentary of his own on the Talmud, known as Piskei ha-Rosh (“Decisions of the Rosh”), Hilchot ha-Rosh, and, less commonly, Sefer Asheri.2

Perhaps because of the scope of this work and its integratory nature, R. Yosef Karo (the Mechaber) named Rosh, alongside Rif and Rambam, one of the “three pillars of halachic decision on which the house of Israel rests.” Another factor was that one of Rosh’s sons, R. Yaakov ben Asher, would go on to cite him extensively in his celebrated code, the Arbaa Turim (better known as just the Tur). It was the Arbaa Turim which was destined to structure the study of halacha henceforth.

Finally, Rosh is known for his musar (ethical) work, Hanhagot ha-Rosh or Orchot Chaim. His personality shines through in this short work, arranged with teachings for each of the six weekdays and Shabbat. I’ll close with a picture of Rosh painted by two complementary impulses expressed in the section for Shabbat, a balance of sternness and humility:

שֶּׁיַּזְהִיר אֶת בְּנֵי בֵּיתוֹ עַל הַתְּפִלָּה וְעַל נְטִילַת יָדַיִם וְעַל בִּרְכַּת הַנֶּהֱנִין:

[The wise man] should warn the members of his household to take care with regards to prayer, the washing of hands [for a meal], and on making blessings of gratitude.

שֶּׁיִּמְחוֹל בְּכָל לַיְלָה קוֹדֶם שֶּׁיָּלִין לְכָל מִי שֶּׁחָטָא לוֹ בִּדְבָרִים:

[The wise man] should forgive, each night before he goes to sleep, all those who have wronged him with words.

Rosh, Hanhagot ha-Rosh

Rosh Reads

Piskei ha-Rosh are printed in the back of standard editions of the Talmud, and are on Sefaria. His responsa are there as well, as are Hanhagot ha-Rosh, though I prefer this edition.

Two great articles about the Rosh, one by Israel Ta-Shma and one by Marc Saperstein, are available in English, but both are secreted away in scholarly essay collections. Both would make all-around excellent reads about medieval Jewish stuff, though, if you’re in the market.

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

Many of you will be familiar with Morfix, probably the best free online Hebrew-English dictionary (its apps are also indispensable, although in my experience, the Android version is a lot better than the iOS version). If not, well, now you know! Morfix also offers Hebrew-to-Hebrew definitions.

Morfix is a actually a lite build of Rav Milim, which is an exceptional, scholarly Hebrew dictionary. Rav Milim requires a subscription, so it won’t be for everyone (and for everyday use, Morfix will take you far). However, for advanced morphological search (meaning you can enter any form of the word) and specialized information like etymology, grammar analysis, and phrases in which the word occurs, Rav Milim is a powerful tool.

Just a heads up, Morfix offers a premium tier (aimed at English language learners) that is different from Rav Milim, so make sure you’re on the Rav Milim site to try it out or purchase.

Rosh on Twitter

ICYMI…

Next Week

Next time we’re hanging out with R. Yaakov ben Asher, son of the Rosh and author of the epoch-making law code, Arbaa Turim.

As Israeli writes in the introduction to Yesod Olam: in the Berlin 1848 edition, Part 1, see the page numbered 1 (following page א; or, page 74 in the pdf); Part 2 is here.

Not to be confused with Haggahot Asheri, a commentary written on Piskei ha-Rosh by (most likely) R. Yisrael of Krems, great-grandfather of the Terumat ha-Deshen, who is himself sometimes known as “the Asheri.”