Coffee with the Tur

☕ R. Yaakov ben Asher, son of the Rosh, sought to make Jewish law widely understandable so that more could walk in its ways. In the process, he structured the study of halacha forever after. NBD.

Welcome back to the Middle Ages—but not for long! We’re starting to get at the cusp of modernity. Today we’re hanging out with the Tur, next week with the Ran—and after that, well, we start to get into the earliest possible boundary of the modern era. You have to be a special kind of nerd (hi) to be scintillated by periodization debates, but hear me out: they’re actually intensely meaningful. Do you think the roots of the modern world we recognize around us go back as far as Humanist (“Renaissance”) Italy? Does that even apply to Jewish (or Islamic, or Japanese) culture? Do we draw the line of Jewish modernity at the Spanish Expulsion(s), or the Shulchan Aruch (spoiler alert: my favorite position), or maybe political emancipation (France, 1789)?

Each of these positions contains within it ideas about what makes our world different from the foreign country that is the past. The Humanist explanation highlights habits of mind (the historiographical term for this is mentalité) while emancipation emphasizes the emergence of the nation-state. Some markers are external to the Jewish community, others internal; this too is an idea about the locus of power in Jewish history. The Tur, who died c. 1340 (making him a contemporary of Dante), is still, by all accounts, within the precincts of the medieval world. But he sowed seeds that would flower into early modernity.

In this issue:

Preparations for the Task of a Lifetime

R. Yaakov ben Asher, better known as Baal ha-Turim or simply Tur, was one of several scholarly sons of the Rosh, including his brothers Yechiel (named for their grandfather) and Yehuda. It was Yehuda who inherited their father’s plumb position in Toledo after his death, and by most accounts Yaakov lived a quiet life of modest, even bare, means. Yet it was Yaakov who would profoundly shape Jewish history forever after.

With his downcast gaze and melancholy look, he seems like a fellow introvert in a common, adorable depiction that you’ll find on Wikipedia and many other sites. As best I can tell, this is a colorized version of an illustration from a set of postcard images of many famous rabbis drawn by the Viennese Jewish artist Meir Kunstadt around the turn of the twentieth century. (Please, if there are any art historians or enterprising sleuths among us who can confirm, let me know!) Kunstadt is known for his haggadah illustration depicting the four rabbis of Bnei Barak as members of the noted Sofer family: R. Akiva Eiger, The Chatam Sofer (R. Moshe Sofer), R. Avraham Sofer and R. Simha Bunim Sofer. It seems that many of the other images of Rishonim out there derive from this set of postcards, including Rashi, Ramban, and R. Yosef Karo. You can see a colorized postcard of Tur here and compare the lithograph to the color version of Ramban here, both held by a library in South Carolina. Despite the modernity of these depictions, I find that I relish the opportunity to picture Tur and friends.

Yaakov was already in his thirties when he fled the rising political and popular anti-Jewish violence in Germany along with his father. He, too, was a cultural transplant who united Ashkenazi learning with Sefardi approaches to halacha. But for all his father’s remarkable adaptations and sense of mission around intensifying local knowledge of the Talmud, it was left to Yaakov to operationalize this lofty goal. Yaakov decided to write a law code, a risky move in a land enamored of Rif and Rambam. But Yaakov made a wager, that a new code, replete with sources and organized practically, was sorely needed to educate a generation of rabbis and judges.

In preparation for the task, the Tur first studied Rambam’s Mishneh Torah intensively and prepared a condensed summary of his father’s Talmud Commentary called Piskei ha-Rosh. He also reviewed the practical rulings of the Rosh’s responsa. While back home in Ashkenaz, responsa were considered individual, Tur realized that in Sefarad they could be applied more broadly. He ended up educating many, many generations, right up to our own day.

The Arbaa Turim

R. Yaakov ben Asher’s masterpiece was the Arbaa Turim, “The Four Rows,” a title that alludes to the quadripartite superstructure of the code as well as the four rows on the breastplate (choshen) of the Kohen Gadol (High Priest). This storied part of the Kohen Gadol’s wardrobe, described in detail in Sefer Shemot (Exodus), was adorned with four rows of precious stones signifying the Twelve Tribes and also held the Umim and Tumim, instruments uniquely capable of rendering judgements.

The code was designed with utility in mind: the first two Turim were addressed to future rabbis. Volume one, called Orach Chaim (“The Way of Life”), was innovatively designed to follow a Jewish man through a typical weekday, then Shabbat, followed by the annual cycle of holidays. The second Tur, Yoreh Deah (“Instruct in Knowledge”), included everyday areas of the law needed by rabbis, such as kashrut, niddah, and brit mila. The second set of Turim were intended for those training to become dayanim, rabbinical court judges. Even ha-Ezer (“The Rock of the Helpmate”) deals with family law and Chosen Mishpat (“The Breastplate of Judgement”) with civil law.

Note Tur’s careful description of the organization of the first Tur and its purpose:

ואין רצוני להאריך בראיות אלא להביא דברים פסוקים ובמקום שיש דעות שונות אכתבם ואכתוב אחרי כן מסקנת אדוני אבי הרא"ש ז"ל…החלק הראשון סדרתי בו סדר היום איך יתנהג האדם מעת קומו עד שכבו…החלק השני סדר יום השבת איך יתנהג בכבודו…החלק השלישי סדר מועדות והלכותיהם ומגילה וחנוכה ור"ח והתעניות…וראיתי עוד לעשות סימנים לכלול כל ענין וענין במלות קצרות ולכתבם בתחלת הספר במספר במנין למען היות נקל לבקש כל ענין וענין.

It is not my intention to be lengthy, bringing proofs, but rather bringing decided matters; and where there are differing opinions I will record them, writing afterwards the conclusion of my father and master, the Rosh, of blessed memory… In the first part, I ordered it according to the order of the day, of how a man behaves from the time he awakens until he lies down to sleep… The second section is the order of the day for Shabbat, how he should behave in its honor… The third part is the order of the holidays and their laws, including Megilla [Purim] and Chanukah, Rosh Chodesh and the fasts… I also saw fit to make section headings containing each matter with brief words and to write them at the beginning of the book, with numbers accounting each, such that it will be easy to seek each matter.

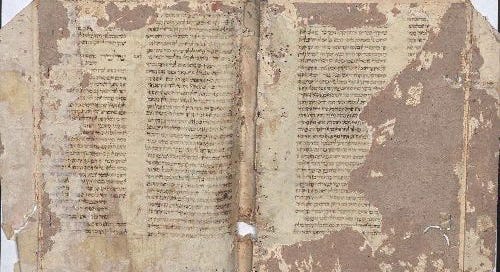

The Tur was, against the odds in Rambam country, quickly adopted for its comprehensive nature, inclusion of a wide array of approaches, fidelity to the shape of the discussions in the Talmud, fantastic organization, and general helpfulness. It was one of the first Hebrew books to be printed and was subsequently published and disseminated in great numbers. When, in the early sixteenth century, R. Yosef Karo (the Mechaber, “the Author”) sat down to write a definitive law code for the new age, he chose to build it according to the blueprint of the Arbaa Turim. This code would become the Shulchan Aruch, which continues to define halachic discourse and lived Jewish practice here in the twenty-first century. Many of the words familiar to us from the patois of the Mechaber are R. Yaakov ben Asher’s. (Copying was a sign of respect before Romanticism.) The Tur is alive on our lips.

Another Lens on the Tur: The Torah Commentary

The Tur also wrote a commentary on Chumash (the five books of the Torah) that remains popular. In it, Tur favors peshat (contextual or “plain”) readings over allegorical or Kabbalistic ones. He reviews the views of major commentators, including Rashi, Ibn Ezra, and Ramban—although he intentionally leaves out Ramban’s sod (mystical) explanations, as he did not consider himself an initiate into Kabbalistic matters. However, Tur begins his comments with brief notes on remez, hinted aspects of the text, and gematriot, letter-number symbolism.

Interestingly, it was these brief notes that were first printed alone, in Constantinople in 1500 and 1514. It was some three hundred years later, in 1806, that the full (or “long”) commentary was printed. Each part displays different aspects of the Tur: his piety and mythical imagination in the “short” commentary and his thoroughness and search for clarity in the “long” commentary.

Readings on the Tur

I love Al HaTorah’s online edition of Arbaa Turim, the Tur-Shulchan Aruch, and full Torah commentary (“short” one here). These are also available on Sefaria with some English translations (see here for the “long” Torah commentary).

Take a deep dive into the Tur’s methodology and the influence of his father in Dr. Judah Galinsky’s “Ashkenazim in Sefarad: The Rosh and the Tur on the Codification of Jewish Law,” Jewish Law Annual 16 (2006): 3-23.

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

Okay, today I’m giving away a real trade secret. This gets a bit into the weeds but it’s so good, so don’t go running away just yet because German. Back in 1916, a fellow by the name of Eduard Mahler (he was an astronomer-turned-historian) published a book of date tables for the Hebrew years 4000-6000 called Handbuch der jüdischen Chronologie. If you want to confirm the day of the week of the first night of Sukkot in the year 1305 CE (say, because it’s a significant date for your dissertation topic), Mahler’s your guy.

Now yes, we have algorithms for that sort of thing nowadays, but dates are tricky. There’s the whole Julian-Gregorian shift, different ways of reckoning civil leap years, and all the quirks of our lovely lunisolar calendar. So when it’s important to be exact, I always check computerized conversions of pre-Gregorian dates against Mahler.

To check out the tables, you’ll want to click on the link called Anhang. Tabellen. You can download a PDF or browse it online. The key is on the first page and you know enough Germanic (English!) to decode it, promise. If all else fails, try saying the word out loud! Old grad school trick. Spoken German sounds more like spoken English than written German looks like written English.

Tur on Twitter

Next Coffee Date

As promised above, next week we’re going to spending time with the Ran, the late, great commentator of the school of Ramban and Rashba.