Coffee with Abravanel

☕ Abravanel reached the glittering heights of Iberian society and lost it all—twice—and rebuilt in Italy, all while writing paradigm-shifting works of Tanach commentary and humanist philosophy.

Happy late medieval Tuesday! Or is it early modernity? Abravanel’s eventful life spans several key features that we, in our comfortable retrospective view, can identify as modern. We’ll see that humanistic currents reached him already in his hometown of Lisbon, Portugal, and came to fruition in Italy, where he settled after the traumatic Spanish Expulsion of 1492.

The Iberian expulsions—the united kingdom of Aragon-Castile was the first in a series of expulsions that left Iberia bereft of official Jews from 1497 on—are events of such magnitude that they are often suggested as a dividing line between the medieval and early modern worlds. Other date candidates for the “end of the Jewish Middle Ages” include the publication of the Shulchan Aruch (Venice, 1565/6; I like 1571, the first printing with Rema’s glosses) or even as late as political emancipation of Jews (1781 or 1791, depending on how you define it). I like to quip that no one got up one morning and said, “Oh great, it’s modernity now,” but the first of May 1492 is pretty close, tbh. On that day, the Order of Expulsion was promulgated publicly, officially ending the Jewish communities of Castile and Aragon, the largest in Europe and dating back to antiquity.

For all the persecution that Jews had suffered on the peninsula, it had offered them, under Romans and then Visigoths and then Muslims and finally Christians, more integration than anywhere else in Europe. For Iberian Jews, and for statesmen like Abravanel in particular, it was a lot like present-day America expelling all its Jewish citizens. It must have seemed like the slamming down of the gates of history. This is the story of how one extraordinary person lived through it and, against all odds, thrived.

In this issue:

From Portugal with Love, then Intrigue

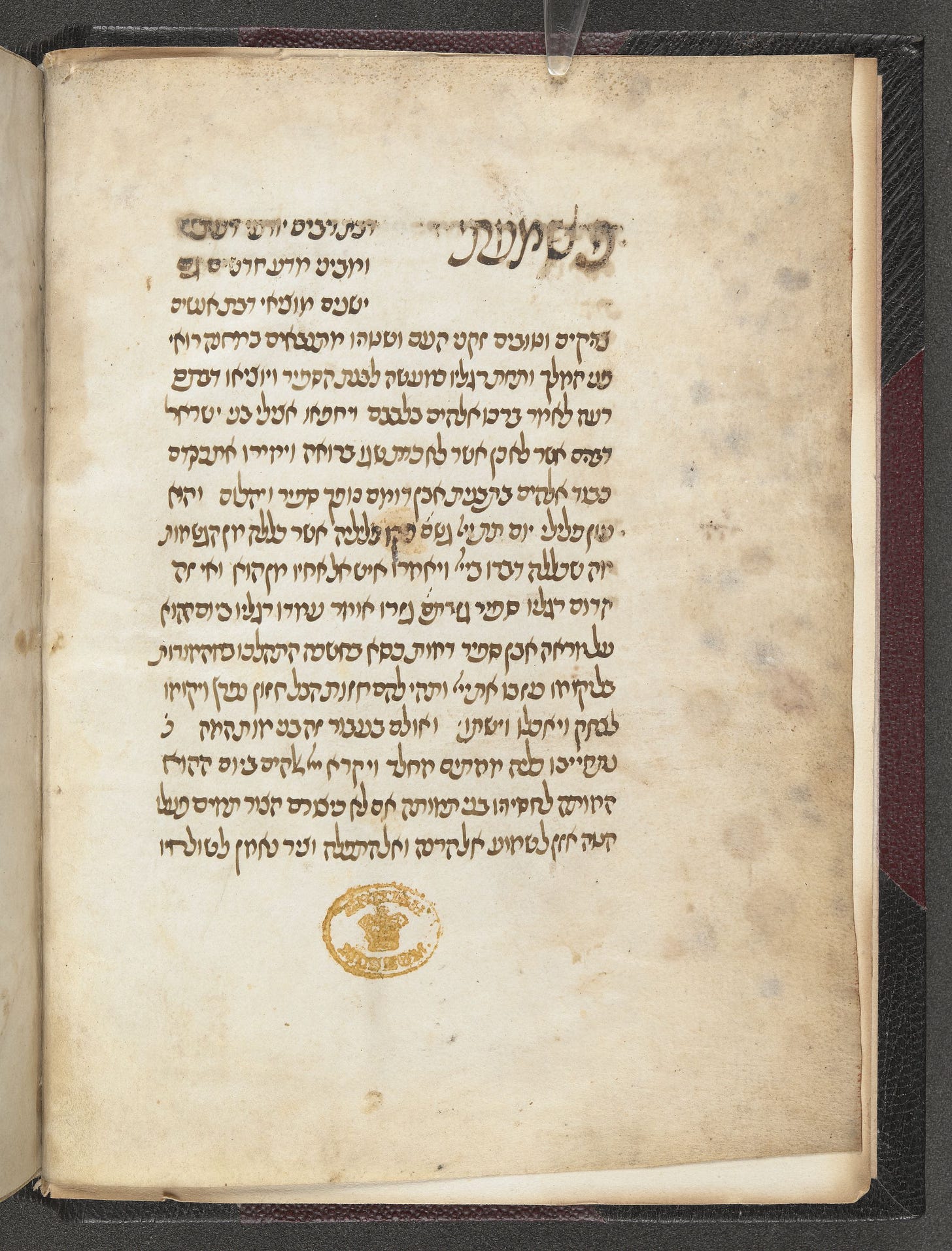

Don Isaac Abravanel, or Dom Yitzchak Abarbanel, or at any rate a man by the name of some combination thereof, was born in 1437 to one of Jewish Iberia’s first families. A quick excursus about names and standardization: one of the many ways we’re captives of our times is the degree of standardization we expect. At the turn of the fifteenth century, vernacular languages were wildly diverse and still at the beginning of being textualized—captured in written form. In the courts of Portugal, our Rabbi Yitzchak garnered the honorific dom; when he fled to Castile, he became don, and had he traveled to King Ferdinand II’s Aragonese domain,1 he would have been en. He would have had to strain to understand Castilian2 (too bad it wasn’t Galego), but gotten by. And then we have the matter of Abarbanel/אברבנאל. “Abravanel” is the prevalent transliteration in academic literature. However, to me the א-ל at the end is a telltale theophoric compound and points to a Hebrew as opposed to vernacular origin. There’s the idea out there that the name is an acronym of av bei rabban bnei Kel (or similar variations), but this could be a post-hoc rationalization.3 We have early evidence for both pronunciations: the explicit vocalizationאַבַּרְבִּינֵאל4 in support of the traditional Abarbanel, as well as an earlyאבראבניל5, in support of Abravanel. I give a slight edge to the former because it comes from a nearby, Italian contemporary of Don Isaac/R. Yitzchak’s, but both are contemporary. Here, I’ll go with Abravanel.

According to family tradition, noted by R. Yitzchak in his works, the Abrabanels were descendants of the Davidic dynasty, who had made their way to Spain already in antiquity. The Abravanels crop up in our historical records only around 1300 in Castile. During the mass anti-Jewish riots of 1391-2, Shmuel, Yitzchak’s grandfather, was forcibly converted to Christianity. Though he attained high office as a Converso, Shmuel eventually fled to Portugal where he was able to return to Judaism. Shmuel’s son Yehuda Abravanel, Yitchak’s father, rose to prominence as a financier to Portuguese royalty, a role inherited by Yitzchak upon his father’s death in 1471. Yitchak was not only an extraordinarily wealthy moneylender but a power broker, merchant, and communal leader who raised large ransoms on behalf of the Jewish community.

The incipient humanism abuzz among the Christian intellectuals with whom he brushed shoulders influenced Abravanel’s early works. These included essays in philosophy and theology as well as the first of the Tanach commentaries for which he would become famous.

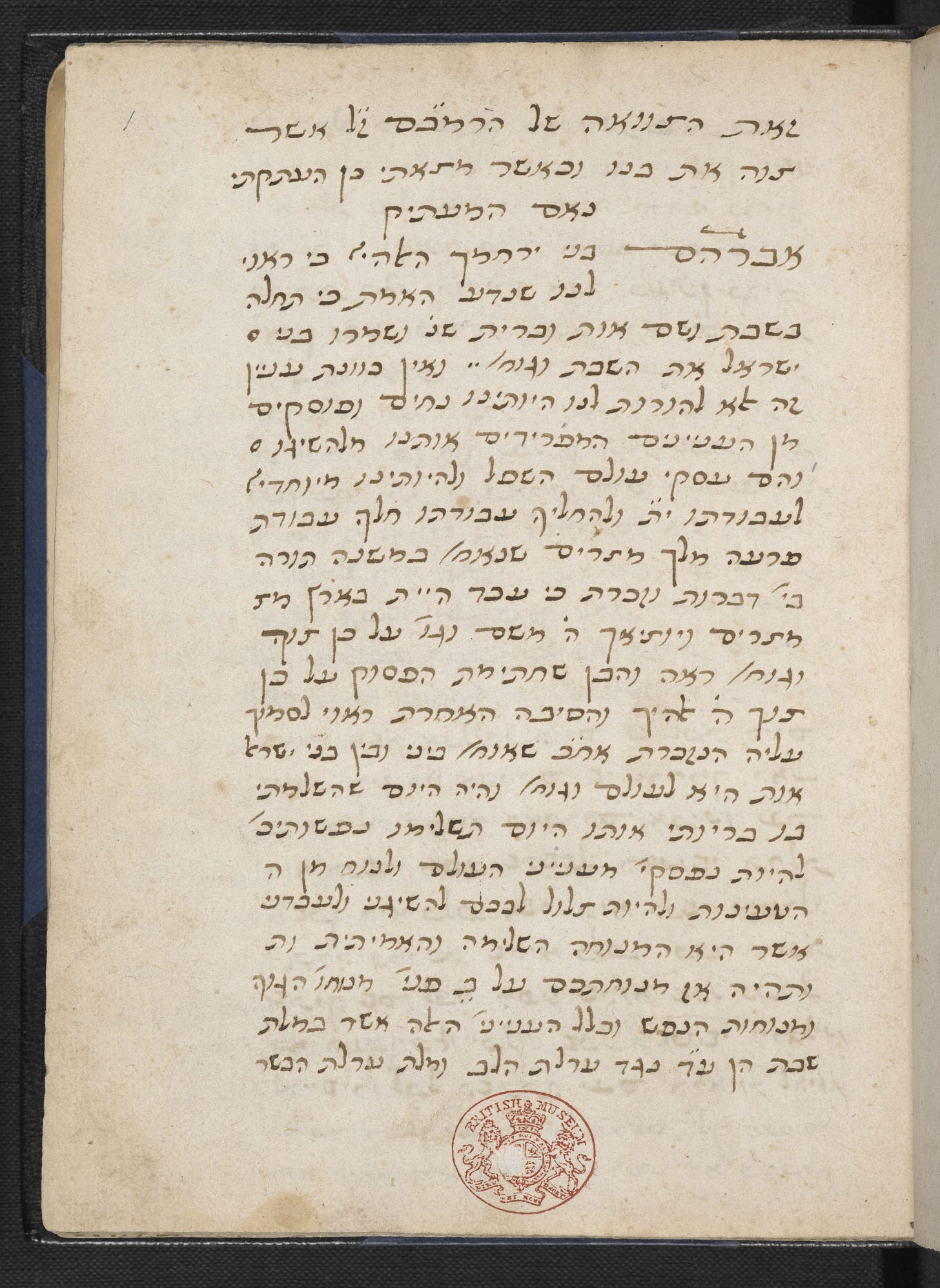

Then, in 1481, King Alfonso V of Portugal died, leading to a bitter political struggle by his heir to wrest power from the Portuguese nobility. Implicated in the nobles’ rebellion, Abravanel was compelled to flee Portugal and was sentenced to death in absentia. He arrived in a Castilian border town under cover of night (according to his telling in the introduction to to Neviim Rishonim)—the same kingdom from which his grandfather, only a generation earlier, had himself fled.

Rebuilding in Iberia, then Italy

At the time he arrived in Castile, Abravanel was about 46 years old. Nevertheless, he started all over again and reestablished his wealth, power, and prestige in short order. He became a tax farmer (an administrator of tax revenues) and backed loans financing Ferdinand and Isabella’s successful campaign against Granada, the last bastion of Islamic Spain. He also continued his commentarial work. In Portugal, he’d written on difficult sections of Shemot and started his commentary on Sefer Devarim; now he turned to Yehoshua, Shoftim (Judges), and Shmuel.

In the employ of Castile’s most powerful cardinal, holding debts owed by the Crown, Abravanel never saw it coming: the decree—convert or leave Spain. He summoned his financial prowess and personal fortune in attempt to reverse the Crown’s decision. He was unsuccessful.

And so, Abravanel, now in his mid-fifties, followed a path trod by many Iberian exiles alongside him: to Naples, Italy. There he started over, yet again. His rise to power and royal employ was, again, meteoric, by his own account. (Abravanel was not much for tropes of humility, another nascent modernism.) He built up his library and picked up with his writing, working on the commentary to Melachim (Kings) and the important theological work Rosh Amana. And then? The French sacked Naples just two years after his arrival, in 1494. His library destroyed, he fled along with the royal family to Messina. The period that followed saw Abravanel moving from place to place in Italy, finally settling in Venice, where he negotiated commercial treaties on behalf of the Venetian senate with various entities, including, wait for it, Portgual.

However, this late Italian period, in the soft glow of the “Renaissance,” was a productive literary period for Abravanel, in which he completed his commentary on Devarim (Deuteronomy)—begun all the way back in Lisbon—as well as a number of other Tanach commentaries, works on messianism and what might be called a proto-philosophy of history, his commentaries on the Passover Haggadah and on Pirkei Avot, philosophical-scientific works, and a commentary on Rambam’s Moreh ha-Nevuchim (Guide of the Perplexed). His son, Yehuda, also known as Leone Ebreo/Leo Hebraeus, who would exemplify Jewish achievement in early modern Italy.

Abravanel’s Paradigm-Shifting Works

Like his life, Abravanel’s works are influenced by the currents of change in the world around him. His philosophical works take up distinctly fifteenth and sixteenth century fascinations, including dogmatics, which inspired renewed engagement with Rambam’s Thirteen Principles, and historiographical thinking, as well as a unique amalgam of Judeo-Arabic and humanist philosophical traditions.

Abravanel’s Tanach commentaries build upon the classical commentaries, but especially Ramban’s and Ralbag’s. (We haven’t had a chance to talk about Ralbag yet, but don’t worry, he’s coming in Rishonim Series 2!) Ralbag’s Tanach commentary in particular foreshadows some of the features of Abravanel: he breaks up the text into sections (the fancy word for this is pericopes) and writes mini-essays of two types on the text. Abravanel takes these forms and develops them further, with the greater prolixity that characterizes later writing. He, uniquely, begins each of his pericopes, which he marks methodically and distinctly from Ralbag’s, with a series of questions. He reviews, he considers, he opines. Abravanel’s commentary was influential upon modern Tanach commentaries, particularly Malbim’s.

Abravanel Reads

On Sefaria, you’ll find a number of Abravanel’s works, including the (timely for now) commentary on the haggadah. If you’re looking for a print copy, Mosad ha-Rav Kook has a nice one and Artscroll has an English translation.

A recent and solid intellectual biography of Abravanel is Cedric Cohen-Skalli’s Don Isaac Abravanel: An Intellectual Biography. (If you’re a Scribd subscriber, which I can recommend for their excellent selection of Jewish Studies books, it’s available there.)

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

As we enter into modernity, it seems fitting to drop in the YIVO Encyclopedia today. One of the regions which would attract many of the Jews fleeing the expulsions and violence of Western Europe was, of course, Eastern Europe, including a few members of the Abravanel clan. Written by scholars, illustrated with photographs and many material objects, it’s a great resource for the early modern and modern periods in Europe.

Abravanel on Twitter

Next Coffee Date

Next time we’re hanging out with R. Ovadia Bartenura, another Italian on the cusp of modernity and eminent commentator on the Mishnah.

Speaking of vernaculars and standardization: monarch’s names present a particular difficulty, in that they have multiple variants, usually including a Latinate version, a local vernacular, a modern vernacular, and for us Anglophones, an Anglicized version. As much as possible, I like to transliterate names to reflect the way they would have been said by the people to whom they refer. But we don’t always know and it can be challenging with, say, Ferdinand II, who’s instantly recognizable in that Anglicized version. Hence, my usage of it here.

Or, to us, “Spanish,” Castilian being the dialect with an army among the manifold Iberian dialects.

The midcentury historian Cecil Roth considered it to be a diminutive vernacular form of Avraham.

In Elias Levitas’ Sefer ha-Tishbi; see Shnayer Leiman, “Abarbanel and the Censor,” Journal of Jewish Studies 19 (1968), p. 49 n. 1 [link to pdf].

In Ibn Verga, Shevet Yehuda; see again Leiman, p. 53 n. 17.