Coffee with the Bartenura

☕ R. Ovadia di Bertinoro, better known as "the Bartenura," wrote a much-loved commentary on the Mishnah as well as three amazing letters about his aliyah to Eretz Yisrael.

New (!) audio version of newsletter:

Welcome back to the cusp of modernity! You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring famous and lesser-known Jewish figures, events, and artifacts. We’re nearing the end of our first series on the great Rishonim, which has brought us right up to the (imaginary) borderline that separates the medieval world from that which we recognize as the beginning of our own time. Up next: a series on famous Hebrew manuscripts, then another set of Rishonim (because there are too many amazing medieval thinkers whose stories need telling).

Last time, we talked a bit about the end of the middle ages and the murkiness of defining that. (If you’re curious to know more, I wrote more about periodization and why it matters here.) Today, we’re back in late fifteenth-century Italy—though not for long—with R. Ovadia di Bertinoro, better known as “the Bartenura.” (Yep, another brand of kosher wine named after a great rabbi. They’ve clearly got my ticket.) Like Abravanel, Bartenura is a liminal figure, rooted in the medieval world yet anticipating, in his interests and writings, the world-coming-into-being.

In this issue:

An Italian Beginning

For all the copious detail we know of Bartenura’s journey to Eretz Yisrael, we know far less about his life in Italy. He mentions his father, Avraham, as a rabbi; his education and professional activities point to him having come from an elite family. Born in Bertinoro c. 1450, he was active in a different northern Italian town, Città di Castello, in finance and probably teaching and other communal activities. (In a municipal document related to his financial activities, he’s called Maestro Servadio di Habramo da Bertinoro—“Servadio” being a vernacular translation of “Ovadia,” a commonly-seen convention in medieval Christian Europe.) He is also known in Hebrew by the epithet “Yare” (יר”א), probably an acronym, possibly from Devarim 33:24, יְהִי רְצוּי אֶחָיו.

It is unclear what Bartenura’s personal fortunes were like in Italy; he does not mention a wife or children in his letters. However, in his unusual chronicle of his experiences with the papal Inquisition, Binyamin Nechemia Elnatan mentions “the sons of R. Ovadia Yare.”1 Certainly, Bartenura traveled to Eretz Yisrael alone, since he at once point in the first letter explicitly mentions ten other Jews on a boat with him, eleven Jews in all. It may be that his wife had died by the time that he left. We do know that Bartenura’s father and brothers remained in Italy, since he addressed them in his letters sent to there. Another factor that emerges is that Bartenura was determined to settle in the Land of Israel. Though invited warmly to stay in the communities along the way in which he taught, Bartenura refused all appointments until he had made his way to Yerushalayim. He was determined.

Rejuvenating Mishnah Study

While still in Italy, Bartenura began working on a full commentary on the Mishnah. (He would finish it in Eretz Yisrael.) There had been a few other commentaries written on the Mishnah by Rishonim, most famously, by Rambam (Maimonides). Most were specifically written on those sections of Mishnah on which there is no Gemara (Amoraic commentary), such as (most of) Zeraim and Tohorot. Rambam’s far-reaching Mishnah commentary was centered around a larger project of uncovering the roots of the Oral Law, an ambition which Bartinura’s more straightforward commentary did not share. However, Rambam had written his commentary in Judeo-Arabic (Middle Arabic written in Hebrew characters). Though Hebrew translations had been made, they were not readily available to most of the non-Arabophone Jewish world, and Rambam’s work remained secreted away. Into this space, Bartenura stepped.

Mishnah study on its own, apart from Talmud study, had waned for centuries. Though there was a scant but recognizable tradition of Mishnah study in Italy, it seems to have been centered in the Byzantine south, not in the northern provinces from which Bartenura hailed. Why Bartenura was moved to comment on the entirety of the Mishnah is unclear: perhaps he saw an opportunity to be of service to his community. Indeed Bartenura’s commentary is derivative, relying heavily, often verbatim, on Rashi’s notes on the Mishnah contained in the Talmud. Where he didn’t have Rashi, Bartenura turned to the (partial) commentary of Tosafist R. Shmuel of Sens, occasionally also to Tosafot ha-Rosh.

Bartenura’s humble-in-scope project turned out to do two prescient things. First, because he did have access to Rambam’s Perush ha-Mishnayot, Bartenura integrated Rambam’s positions with Rashi’s. This melding of Ashkenazi and Sefardi halacha, though continuing a trend, was salient, foreshadowing the greater integration of the two cultural spheres in early modernity. Second, Bartenura’s Mishnah commentary paved the the way for dedicated Mishnah study, which took off in the later sixteenth century, after his death (he died sometime before 1516). This movement was propelled by two disparate concerns: the Kabbalistic (specifically, Zoharic) emphasis on Mishnah learning, and the pedagogic concern in Ashkenaz surrounding pilpul (casuistic Talmud learning) and the too-early introduction of Gemara to young students.

Bartenura’s Aliyah to Eretz Yisrael

In late 1486, when he was in his thirties, Bartenura set out from his home in Castello, bound for the Land of Israel. He made his way to Rome, Naples, Salerno, and Palermo, then sailed from Messina, via Rhodes, for Alexandria, arriving in early 1488. Staying for a time in Cairo, he approached Israel overland, entering at Gaza, lodging at Chevron (Hebron), and finally entering Yerushalayim (Jerusalem).

Bartenura wrote three extraordinary letters about his journey to Eretz Yisrael, which took him close to a year and half due to the stops he made along the way. What makes the letters extraordinary, in particular the lengthy first one, is the lively detail of the eyewitness account. Unlike many premodern letter-writers, who filled their prose with dense allusion to verses from the Tanach, Bartenura’s account is written in natural language, anticipating the historiographical writing to come in the following century.

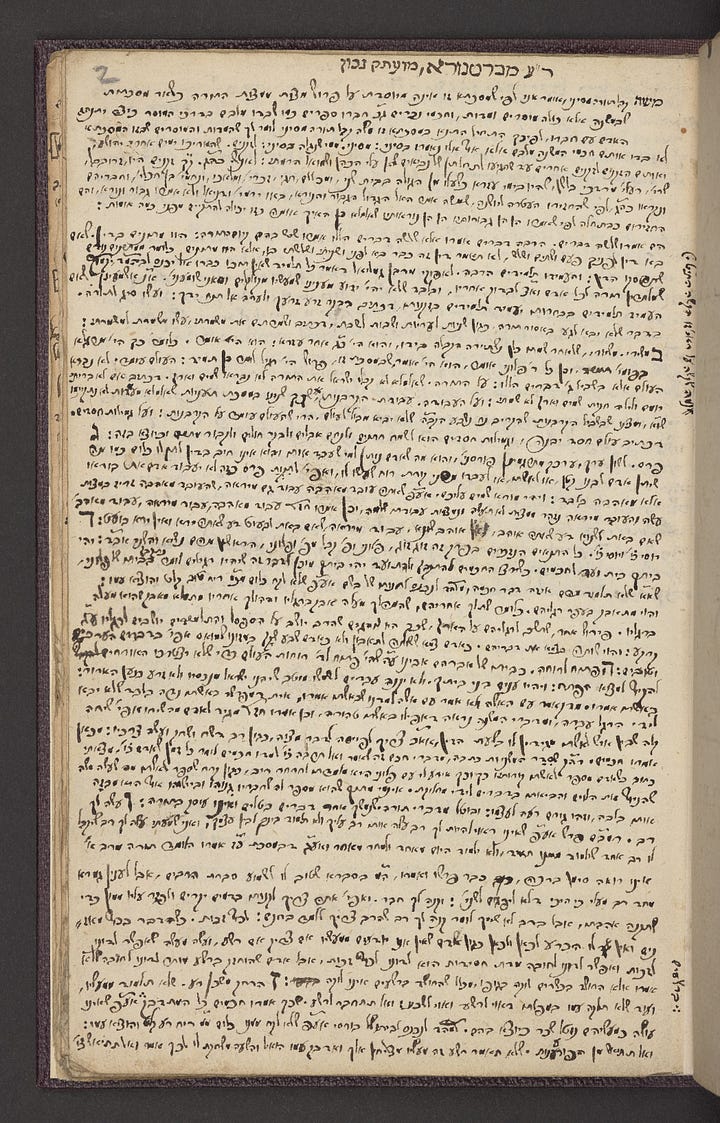

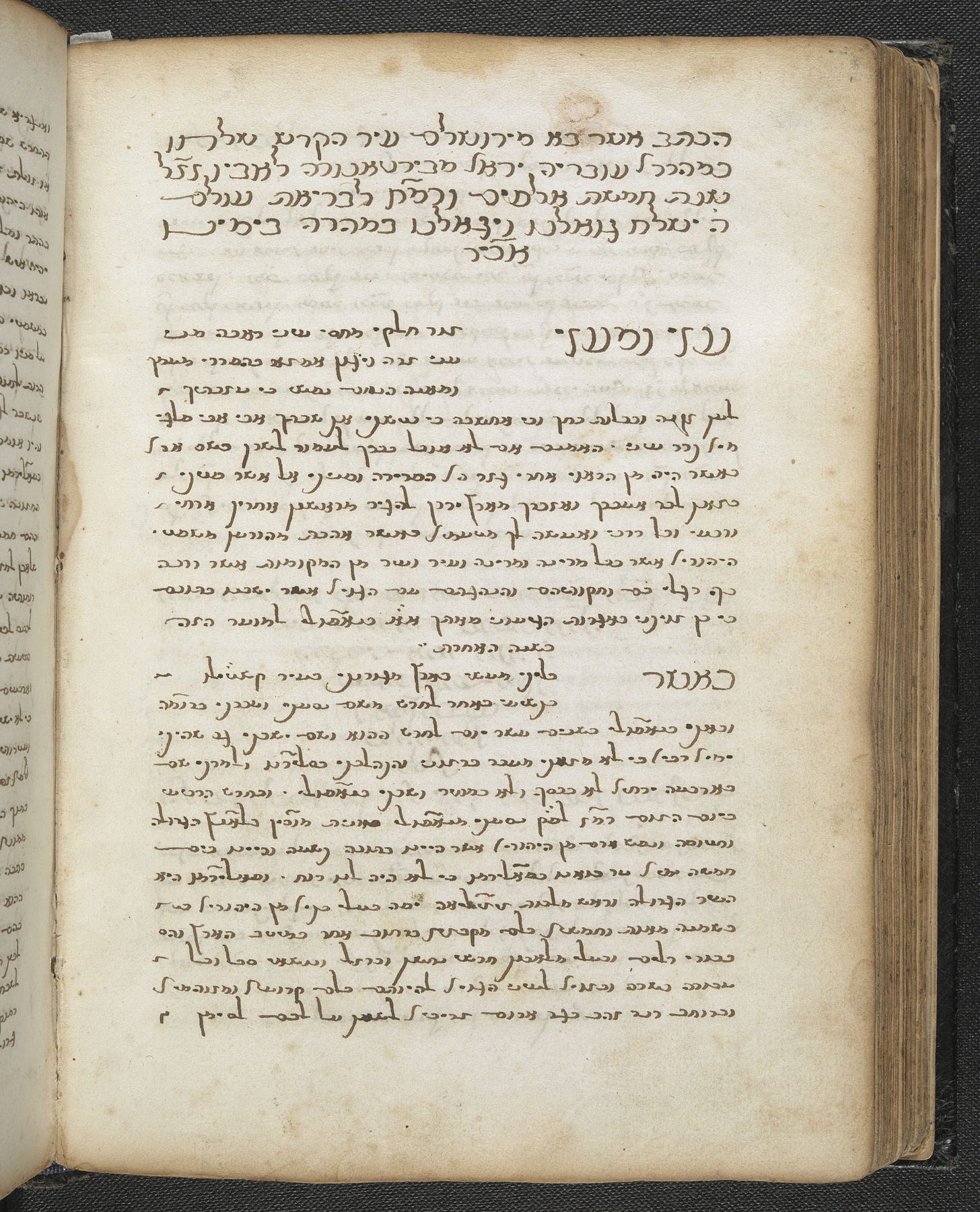

Though there are a handful of manuscripts containing all or parts of the letters, only one, pictured above, is complete and, according to the authors of the critical edition of the letters, almost certainly the source for the rest. Like most codices (manuscripts bound like our modern books), the one containing the letters includes a miscellany of other texts. In this case, they seem to betray the interests of their owner: along with Bartenura’s letters are, among other texts, a Kabbalistic work by the Shelah (the author of Shnei Luchot ha-Brit), “Elef Alefin,” an ornate belletristic poem in which every word begins with the letter alef, and a prayer composed by Bachye Ibn Pakuda, an 11th-12th century figure famous for his works of musar (spiritual ethics). In other words, the codex, produced c. 1600 in Italy, displays the interests of its time and place: lots of Kabbalah, though with a noted rationalist (or, perhaps in its owner’s eyes, humanist) slant. Including Bartenura’s reportage.

In the letters, Bartenura describes his route through southern Italy, then via Rhodes to Egypt, and finally to the Land of Israel, where he settled. In Cairo, he took a curious interest in the Karaite and Samaritan communities he found there, describing what he observed and heard. Here is his stirring description of entering Yerushalayim:

ומרחוק מירושלים כשלשת רבעי מיל, במקום שיש שם כעין מעלות ומתחילים לרדת משם, נגלתה העיר המהוללה, קרית משושנו, ושם קרענו את בגדינו כחובה, וכאשר עברנו עוד מעט נגלה אלינו בית קדשנו ותפארתנו ההרוס, וקרענו קריעה שניה על המקדש.

ובאנו עד שערי ירושלים ונכנסנו בה בשלשה עשר לחודש ניסן רמ״ח בצהרים. בעצם היום ההוא עומדות היו רגלינו בשעריך ירושלים. ושם בא לקראתנו רב אשכנזי אחד, אשר נתגדל באיטאליאה, שמו ר׳ יעקב די קולומבאנו והביאני אל ביתו, ונתאכסנתי עמו כל ימי הפסח.

At a distance of three-fourths of a mil from Jerusalem, at the point where there is a sort of slope and from which one begins to descend, the praised city was revealed to to us, the city of our rejoicing, and there we tore our garments as required. After we proceeded a little bit, we could see our holy Temple and our ruined glory, and we tore a second tearing for the Mikdash.

Then we came up to the gate of Jerusalem and entered into the city, on the 13th of the month of Nisan in the year 248 [AM, = 1488 CE] in the afternoon. On that very day our feet stood in your gates, O Jerusalem. There came to greet us one Ashkenazi rabbi who had been raised in Italy, by the name of Rabbi Yaakov di Colombano, who took us into his home, where I stayed all the days of Pesach (Passover).

R. Ovadia Bartenura, Igrot Eretz Yisrael, Letter 1

Several of Bartenura’s works remain in manuscript, including responsa, chiddushim (novellae or “insights”) on R. Moshe of Coucy’s Sefer Mitzvot Gadol (Semag) and on Rambam’s Mishneh Torah, as well as other letters and piyutim (liturgical poetry). Attributed to him is the supercommentary on Rashi on the Torah called Amar Neke (עמר נקא), although the attribution is a later printer’s and does not appear in manuscripts, and has been called into doubt by scholars on this and other bases.

Bartenura Reads

Bartenura’s helpful Mishnah commentary is printed in many standard editions and is available online on Sefaria (which includes an English translation) and Al-HaTorah.

An excellent critical edition of Bartenura’s Igrot Eretz Yisrael (the three letter about his aliyah) is available here. The introduction, by Prof. Abraham David, is great. There are partial English translations available, most notably in Franz Kobler’s Letters of Jews Through the Ages, Volume One: From Biblical Times to the Renaissance. (Incidentally, the two volumes of this work are excellent sourcebooks.) I’m working on a full translation of the letters, which I’m hoping to have available on my website by the end of summer.

You can hear a lecture on Bartenura’s travel letters by Prof. Elliott Horowitz, from Fordham’s Early Modern Workshop, here. (The workshop votes to place Bartenura over the line of early modernity!)

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

We’re living in a golden age of access to manuscripts, and I’m on a mission to make sure everyone (very much including non-experts!) gets to enjoy them. My post How to Access Jewish Manuscripts demystifies the process and explains what kinds of things you can do with manuscripts and their library records.

Bartenura on Twitter

ICYMI!

https://twitter.com/tamar_marvin/status/1647791078756474881

Next Time

Next coffee date is with another Great Ovadia: R. Ovadia Sforno, the Tanach commentator.

Elnatan’s account of the papal Inquisition was first published by I. Sonne in Tarbiz 2 (1930/31) and later in his 1954 book, מפאוולו הרביעי עד פיוס החמישי.

I really like your work. Started following you on Twitter and I love your threads. I will figure out how to support your work.