Major Manuscripts of the Talmud Bavli and Yerushalmi

📜 The Talmuds have a complex transmission history, but we now have excellent tools for exploring their textual variants. We have just one complete manuscript version of each Talmud.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. We’ve looked at Masoretic codices and important manuscripts of the Mishnah, and today we turn to major manuscripts of the Talmud, both the Bavli and the Yerushalmi. We’ll begin by examining some early statements about the transmission of the Gemara.

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here (and an archive of all audio editions here.)

A quick note: Rather than embed the audio version of the newsletter (a paid feature) at the end of the post, I’m now publishing it separately as a “podcast.” I’ll include a direct link to the audio at the top of each newsletter so it’ll be right there for you, and you can also add it as a private feed to your favorite podcast player (except for Spotify, which apparently doesn’t allow private feeds). You can also find the latest audio at the top of the main page and all audio organized in the Podcast tab, accessible from the top nav bar on the main page.

Also: I fixed the problem with commenting, which is again open to all. Sorry about that!

In this issue:

Transmission of the Talmud

Before looking more closely at the individual manuscripts, a little bit about how the Talmud came to be written down and how it was transmitted. Both the Mishnah and the Gemara, along with the voluminous literature of Chazal (sages of the Tannaitic and Amoraic periods), were “born oral” and remained so for centuries, even after they began to be written down. Though initially forbidden to be recorded in writing, the Oral Law was eventually formulated as text due to the exigencies of the hour. Its textualization process was long and halting, however; students continued to learn Gemara orally from their teachers even after written versions began to circulate. The prevalence of citations from the “Talmud Katan” of the Rif (Halachot ha-Rif) in north Africa and Spain as a means of accessing the Gemara, albeit in abridged form, testify to the difficulty medieval students had in getting hold of the Bavli iteself. In early Ashkenaz, it seems that students had kuntresim, notebooks, of single chapters of the Bavli from which to learn.

We have a few early statements offering clues as to the transmission of the Talmud text out of Bavel (Mesopotamia). A letter found in the Cairo Geniza dated Nisan 953, dispatched from Bavel, probably Pumbedita, records that the the Rav Paltoi, gaon from 842 to 857, had sent a corrected copy of the Talmud to Spain along with commentary explaining the text:

ולא עוד כי מימות עולם ועד עכשיו החכמה מצויה באספמיא…בכמה עתים היו שולחים אל אספמיא בשאלותיהם בימי חכמי הוראה אנשי משנה והיו משיבים אותן וגם הם היו שואלים וסוף בימי אדוננו מרנא ורבנא פלטוי ראש הישיבה ז”ל שלחו לכתוב להם תלמוד ופתרונו וצוה וכתבו להם.

It ever was and still is today, that wisdom is to be found in Spain [Aspamia, i.e. Hispania/España]…over several periods they would dispatch to Spain their questions, in the days of the sages of the Oral Tradition (Hora’ah), masters of the Mishnah, who would respond to them and they too would ask, until, in the time of our master, our teacher and rabbi Paltoi, the head of the yeshiva, of blessed memory, they [the Spanish Jewish community] requested that a Talmud be written for them along with its explanations and he called for it to be written for them.

Ed. A. Cowley, “Bodleian Geniza Fragments,” Jewish Quarterly Review 18, 3 (1906), 401.

R. Shmuel ha-Nagid (993–1055/6) records, slightly later, an earlier tradent of the Talmud text into Spain. He is cited at length by R. Yehuda ben Barzilai ha-Nasi of Barcelona in the latter’s Sefer ha-Itim:

וחששו זקנים שקבלו מנטרונאי נשיא [בר] חכינאי והוא שכתב לבני ספרד את התלמוד מפיו שלא מן הכתב

…And the elders were concerned [the subject at hand is reciting the Targum on Shabbat], who had received from Natronai Nasi the son of Rav Chakinai, the one who wrote the Talmud for the people of Spain from his mouth and not from a written text…[emphasis added].

Sefer ha-Itim 175 [also in B. M. Lewin, ed., Otzar ha-Geonim (Haifa, 1928), vol. 1, 20]

This Natronai is not the better-known gaon of Sura who served as rosh yeshiva in the mid-800s, but Natronai bar Chakinai (or Chaninai), an exilarch who was apparently exiled from Bavel in 773. This is an explicit claim that the Gemara was written down from oral teachings in the mid-eighth century (perhaps not globally or uniquely, but for the benefit of the Jews of Spain). However, writing in the late 1100s, Rambam states that he consulted versions of the Gemara that were 500 years old and which had reached Egypt, meaning c. 600!

וְטָעוּת סְפָרִים הוּא וּלְפִיכָךְ טָעוּ הַמּוֹרִים עַל פִּי אוֹתָן הַסְּפָרִים וּכְבָר חָקַרְתִּי עַל הַנֻּסְחָאוֹת הַיְשָׁנוֹת…וְהִגִּיעַ לְיָדִי בְּמִצְרַיִם מִקְצָת גְּמָרָא יְשָׁנָה כָּתוּב עַל הַגְּוִילִים כְּמוֹ שֶׁהָיוּ כּוֹתְבִין קֹדֶם לַזְּמַן הַזֶּה בְּקָרוֹב חֲמֵשׁ מֵאוֹת שָׁנָה

This is a scribal error. For this reason, the halachic authorities erred because of those texts. I have researched ancient versions of the text… In Egypt, a portion of an ancient text of the Talmud written on parchment, as was the custom in the era approximately 500 years before the present era, came to my possession.

Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Malveh ve-Loveh 15:2, trans. Eliyahu Touger (unless otherwise stated, translations are my own)

Ramban, too, speaks of superior, early copies of the Talmud circulating in Spain, as well as those from the school of Rabbenu Chananel:

וכן בספרים המוגהים הבאים מספרד. ומישיבתו של ר״ח ורבינו חושיאל אביו ז״ל מצאתי דלא גרסינן ליה. וכן בנוסחאות ישנות שבספרד ראיתי דלא כתיב בהו הכי

It is also thus in the corrected books that have come to Spain. In addition, [in those] from the academy of Rabbenu Chananel and Rabbenu Chushiel, his father of blessed memory, I found that they don’t have this version [of the text variant he is contesting]. So too in the old versions in Spain, I saw that it is not written this way.

Ramban, Milchamot Hashem to Bava Kama 85b

Ramban’s comment shows that already among the Rishonim, there was vigorous debates and scholarly attempts to establish correct readings of the Talmud text. It also points to multiple early manuscripts available in medieval Iberia for scholars to consult. These manuscripts have not come down to us, even as their echoes remain in these statements of the the Rishonim.

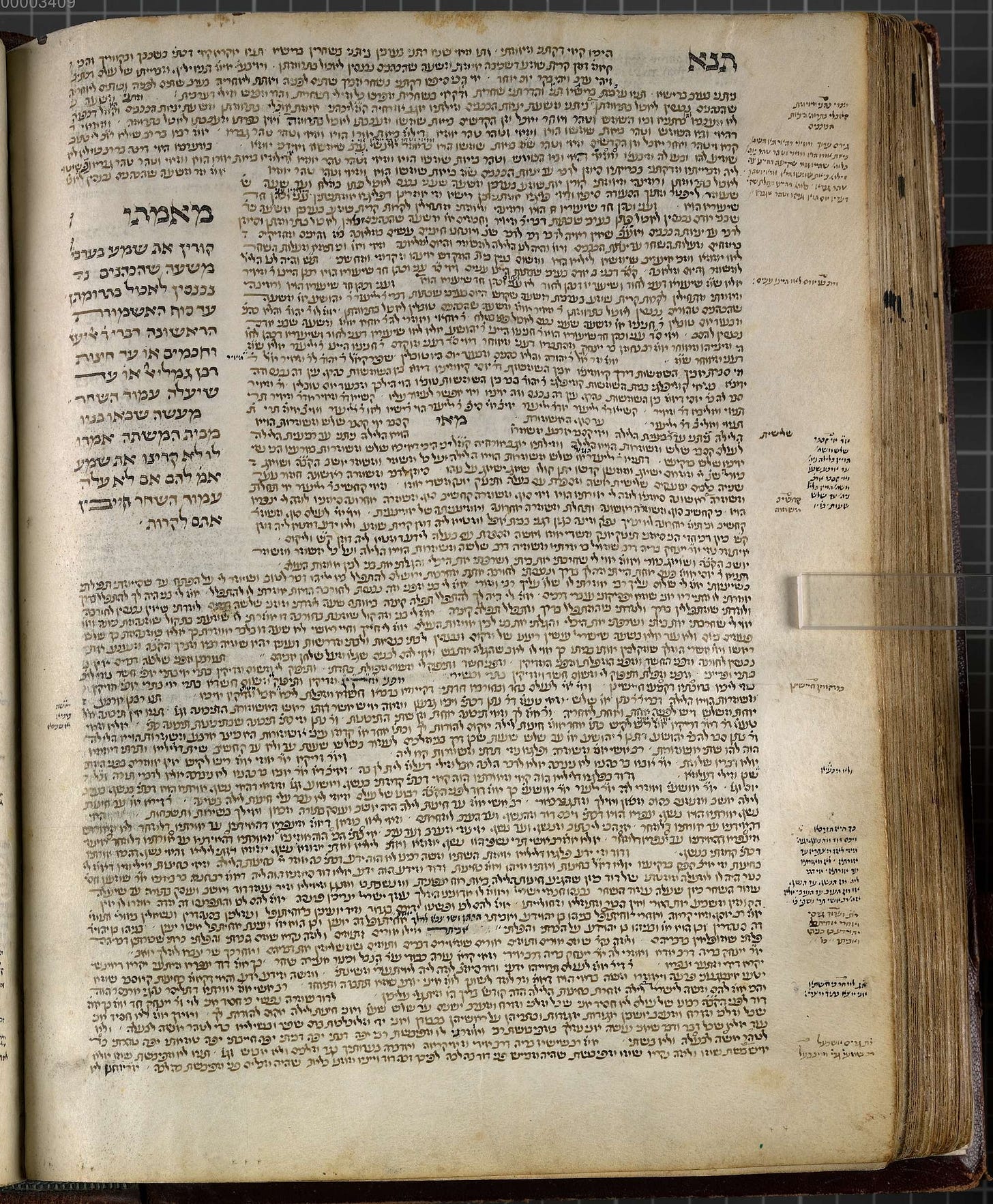

Munich 95: A 14th-Century Complete Talmud Bavli

Because of its length and the manner in which it was distributed in writing, the Talmud Bavli has a complex textual history. This means that each tractate has its own set of important manuscripts that serve as textual witnesses, mostly dating from the late medieval period (13th-15th centuries). These are too voluminous to detail here (look for resources about them below), but we do have one special exemplar containing the entire text of the Bavli: the manuscript known as “Munich 95” or simply “Munich.” Today it’s owned by the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Bavarian State Library) in Munich, Germany, where it’s numbered Hebrew manuscript 95.

The Munich manuscript was completed in 1342 by the Ashkenazi scribe Shlomo ben Shimshon (not to be confused with the 11th-century figure of the same name, who was a teacher of Rashi and eyewitness to the First Crusade and its anti-Jewish violence). Shlomo the scribe wrote in an Ashkenazi semicursive, ostensibly to save space. Even so, it took him 577 pages in total, nearly all of which are extant today. Because it includes the Mishnah as well as the Gemara (as in our standard Talmud today), it is also significant for establishing the text of the Mishnah, as I mentioned last week.

The 19th-century scholar R. Rafael Natan Nata Rabinowitz relied on Munich 95 as the basis of his large-scale work on textual variants in the Bavli, Dikdukei Sofrim.

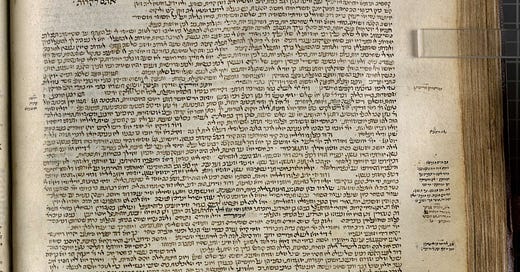

Leiden: A 13th-Century Complete Talmud Yerushalmi

How much access Rishonim in various parts of the Jewish world had to the Yerushalmi (the Talmud of Eretz Yisrael) is the subject of much scholarly debate. Citations of the Yerushalmi abound in medieval halachic literature, but also make clear that the text was not as readily available as the Bavli. A substantial clue, as well as a textual resource, is the complete Yerushalmi1 known as the Leiden Manuscript.

Written in the year 1289, the Leiden manuscript was penned by R. Yechiel ben Yekutiel ha-Rofe (“the physician”) of the famed Roman Anav family. R. Yechiel was a relative of the Shibbolei ha-Leket (R. Tzedekia ben Avraham Anav), and the two apparently studied together under the tutelage of R. Yechiel’s uncle. Himself a scholar, writing mussar (ethics), halachic works, and piyutim, R. Yechiel seems to have produced manuscripts for his own use, at a rapid pace and with many of his own notes and emendations interspersed. His Yerushalmi is written in clear, though now partially faded, Italian script and is bound in two volumes as Leiden University Libraries, Leiden, Netherlands Ms. Or. 4720.

Importantly, this particular manuscript formed the basis for the first print edition of the Yerushalmi, published in 1523-24 by the non-Jewish printer of manifold Jewish works, the Dutch Daniel Bomberg, who operated then in Venice. The Venice edition of the Yerushalmi was edited by Yaakov ben Chaim Ibn Adoniyahu, who also did extensive manuscript sourcing and editing for the important Second Rabbinic Bible, completed by Bomberg in 1525. (Ibn Adoniyahu converted to Christianity sometime after 1527, i.e., after he had worked on both of these texts.) His notes and signature appear in the Leiden manuscript.

Though an important base text, the version of the Yerushalmi that appears in Leiden is arguably a late one, as comparison with Yemenite manuscripts of the Yerushalmi seems to suggest. Another important manuscript for comparison is Vatican Ms. ebr. 133 (digitized here), a 14th-century manuscript which contains all of Seder Zeraim plus Masechet Sotah.

Resources & Reads

A treasure-trove of information on our Talmud and how it got that way is the volume Printing the Talmud: From Bomberg to Schottenstein, edited by Sharon Liberman Mintz and Gabriel M. Goldstein (Yeshiva University, 2006). It’s prohibitively expensive, but you can find some of the chapters by running a search with the full title of the book in Academia.edu.

The easiest way to consult the manuscripts for a given sugya in the Bavli is to use the wonderful tool Hachi Garsinan. I wrote a quick-start guide to using it. You can also use the “manuscripts” tool in the Sefaria sidebar to look at Munich 95.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective.

Complete in the sense of being all that has come down to us today; volume one contains the Orders of Zeraim and Moed, and volume two includes Seder Nashim and Nezikin, plus Masechet Niddah. Presumably, parts of the Yerushalmi, like Seder Kodashim, were once extant (and have been forged, but that’s a story for another time!).

Do we have older geniza fragments that add to the gemara textual tradition? I know we have autographed documents of the Rambam from geniza. Coming from the modern beis midrash, it would be inconceivable that the geniza wouldn't have a bunch of worn out Talmud manuscripts, but maybe the oral transmission prevented such accumulation in the early Medieval period?