From Nasi to Gaon: Leadership in Byzantine Eretz Yisrael

🕍 We continue in our Geonim series with a closer look at the leadership situation in the Land of Israel, which had its own geonim, as well as celebrated paytanim (liturgical poets).

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. Last week, I introduced the Geonic period, exploring the major sources of the period, the problematics of determining historical facts for the earlier “dark” period for which we have few contemporary sources if any at all, and the work of the Savoraim, who inherited and redacted the Oral Torah of the Amoraim. Today, we examine another obscure period of Jewish history, that of Eretz Yisrael under Byzantine rule, during which its leadership was decimated and rebuilt. By the ninth century, a gaon was serving in the capacity of spiritual and political head of the community of remaining Jews in the Land of Israel.

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here (and an archive of all audio editions here.)

In this issue:

The Geonic period, though centered in Bavel (Babylonia), also had an important center in the Land of Israel: it was both symbolically important, as a continuation of ancient office in the sacred Land, and also, at some times, holding real political and religious power.

Byzantine Eretz Yisrael

Eretz Yisrael was ruled, following the division and Christianization of the Roman Empire, by the eastern empire headquartered in Constantinople as part of its southern provinces, which included Syria (encompassing the Land of Israel) and Egypt. During this time, the Byzantine Empire, which very much understood itself to be the continuation of the Roman Empire, spanned the entire Eastern Mediterranean, from southern Italy, Greece, and Anatolia (today’s Turkey) down to Egypt. It was officially Orthodox Christian and largely Greek-speaking. In contrast, the southern provinces were home to various religious minorities, especially non-Orthodox Christians and Jews, who spoke Aramaic and in Egypt, Coptic. These cultural differences were to prove thorny for the empire. It repressed minority groups and taxed them heavily.

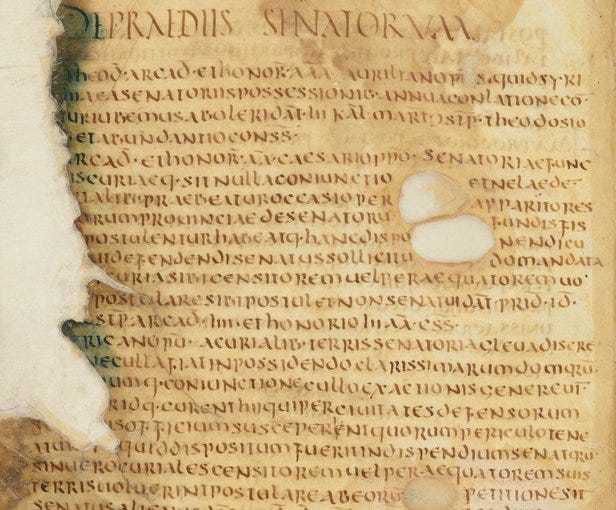

Theological anti-Judaism, developed by the early Church Fathers, placed the blame for their savior’s death squarely on Jewish shoulders and viewed Jews as obstinate and perfidious (two words from the Latin used commonly to describe Jews). These attitudes filtered into the Empire’s functioning, though historians debate just how much. Consider the opening words of the definitive Roman law code known as the Theodosian Code:

Wherefore, although according to an old saying [of the Greek Hippocrates] “no cure is to be applied in desperate sickness,” nevertheless, in order that these dangerous sects which are unmindful of our times may not spread into life the more freely, in indiscriminate disorder as it were, we ordain by this law to be valid for all time.

Novella III, translated in J. R. Marcus, The Jew in the Medieval World, rev. ed., Ed. M. Saperstein, (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1999), 5. The Latin original is found in Theodosiani libri XVI, ed T. Mommsen and Paulus M. Meyer (Berlin, 1905), vol. 2, 8.

Paradoxically, however, such theological stances created space for Jews to exist in Christian society. The “Doctrine of Witness” promulgated by Augustine of Hippo (a city on the coast of North Africa in a district of the empire known as Numidia) maintained that Jews were to be preserved as a debased minority so that they would be present to witness the return of the Christian savior and acknowledge the error of their ways. As noxious as this doctrine was and, sadly, continues to be in some quarters, it also allowed for Jews to live according to their religious laws (this was the “preservation” part of the doctrine). Thus the Theodosian Code, a landmark piece of legislation that influenced Jewish life in Christian lands for centuries to come, denied Jews positions of power over Christians, such as holding public office or adjudicating in court cases involving Christians, but allowed for Jews to maintain already existing synagogues. New ones, however, were strictly forbidden from being buit.

The Nesiut (Patriarchate) and the Yeshiva of Eretz Yisrael

The Roman administration of Eretz Yisrael at first recognized officially the nasi, the continuation of the office of the head of the Sanhedrin (Jewish supreme court of seventy), which went back to Second Temple times. In the early 5th century, when the “last nasi” Rabban Gamliel VI was accused of abrogating the types of laws just cited from the Theodosian Code, recognition and Roman protection of the nesiut or patriarchate was withdrawn. The historical record is poor for the next several centuries, until findings from the Cairo geniza begin to light it up again for the ninth century on, but it seems that a yeshiva functioned in Tverya (Tiberias) in northern Israel, its heads known as rashei ha-perakim (“chairmen”).

Some time after that, the title of the person at the yeshiva’s healm settled at gaon, just like his colleagues in Babylonia, now Iraq. However, the gaon of the academy of Eretz Yisrael combined the roles of two separate offices in Bavel, that of the spiritual leader and the exilarch. In other words, he was a political representative to the government after the Muslim conquests as well as the leader of the yeshiva. This combined office is generally referred to in scholarly literature as the patriarchate, in distinction from the gaonate and the exilarchate in Bavel. Like the Geonim of Bavel, the gaon of Eretz Yisrael had jurisdictions (reshuyot) that sent him queries and monies.

Classical Piyut

An additional form of leadership that developed during this early medieval period in Eretz Yisrael was the spiritual leadership of composing poetic prayers (piyut), many of which remain with us and on our lips to the present day. Written in dense, exceedingly difficult Hebrew dotted with neologisms—novel coinages of words that didn’t previously exist in Hebrew—and drawing upon Midrashic language, piyut is hauntingly beautiful and tricky to navigate. The later poets of medieval Spain would largely eschew paytanic Hebrew for what they considered purer and clearer Biblical idiom, but the classical poets’ language remains breathtaking and unique.

Rav Saadia Gaon, one of the last great geonim who we’ll soon meet, already placed the classical paytanim, in the introduction to his Hebrew lexicon Sefer ha-Egron, in the remote past, calling them “ancient poets” (משוררים קדמונים). These he enumerated as: “Yose ben Yose, Yannai, Elazar, Yehoshua, and Pinchas.” Little concrete information is available about these early paytanim, but it has been determined by scholars based on the language, liturgical form, and other characteristics of their creations, that they flourished in the Land of Israel in the Byzantine period.

Yose ben Yose is apparently the earliest, and is estimated to have lived in the 5th century, possibly earlier. Perhaps his best-known piyut is אתה כוננת עולם, which is read on Yom Kippur in the Sefardi and many other traditions. The Cairo geniza has turned up a number of additional piyutim by Yose ben Yose, including two more poems belonging to the genre describing the seder advoda (special service) of the Kohen Gadol (high priest) on Yom Kippur. This demonstrates an intriguing aspect of Jewish prayer as revealed to us by early piyut: on the one hand, the prayer service was fixed to a substantial degree, such that piyut had to be “attached” to it as specific points. Synagogue goers, or at least some of them, apparently knew the prayers so thoroughly that they understood how piyut fit onto their complex framework. On the other hand, it was normative to create poetic prayers to enhance the service and interweave with the standard prayers. These were created in great number and with great creativity, such that the prayers said on different occasions were often fresh and new.

Yannai and Elazar bei-Rabbi Kalir are linked by a late medieval legend which calls Yannai the teacher of Kalir. According to this legend:

אוני פטרי רחמתים. ואמר העולם שהוא יסוד ר’ יניי רבו של רבי אלעזר בר קליר, אבל בכל ארץ לומברדיאה אין אומרים אותו, כי אומרים עליו שנתקנא בר’ אלעזר תלמידו והטיל לו עקרב במנעלו והרגו. יסלח ה’ לכל האומרין עליו אם לא כן היה.

Onei Pitrei Rachmatayim [the name of a piyut]. It is known that this is the work of R. Yannai the teacher of R. Elazar bar Kalir, but in all of Lombardy it is not recited, because they say of him that he grew jealous of R. Elazar, his student, and placed a scorpion in his shoe, killing him. May G-d forgive those who say so if it was not actually thus.

A 14th-century or later note added to a commentary of R. Efraim of Bonn on piyut in State and University Library Carl von Ossietzky, Hamburg, Germany Cod. hebr. 17.1

If indeed they were master and disciple, or merely contemporaries, this would indicate that they both lived before the Muslim conquest of Eretz Yisrael in 638/9, since Kalir, ostensibly the younger of the two, always mentions Edom (Rome/Christianity) as the oppressor of the Jewish people rather than Yishmael (Islam). Yannai’s work was largely unknown to us until the discoveries of the Cairo geniza, which restored a great deal of his piyutim. It does seem that Yannai’s foundational work, which served as exemplars for later paytanim, was eclipsed by the work of Kalir, whose poems proved enormously popular and influential and still dot our liturgies. (We’ll be saying a large number of Kalirian creations later this week in the Kinot of Tisha be-Av.)

The Muslim Conquests

In the early decades of the 7th century, Islam burst onto the scene of the Middle East. This was, of course, a complex process, as were the factors that led to its military campaigns, themselves protracted affairs in many areas. However, by c. 650, the world looked substantially different than it had in 600. The Byzantine Empire had lost its southern provinces; Sasanian Persia had lost theirs, too. These lands were now united under a (Sunni) caliphate, which meant that the two Jewish population centers of Bavel and Eretz Yisrael were now under united rule. This enhanced cultural exchange, communication, and economic ties among Jewish communities.

The warfare employed so skillfully by the Muslim armies was desert warfare, and the administrators of the new regime preferred to rule out of cities on the edge of the familiar desert. Some existing cities were suitable for this purpose, such as Damascus, the capital of the Umayyad caliphate. In many cases, however, this preference impelled the construction of new cities, including Basra in Iraq, Fustat in Egypt, and Qayrawan (Kairouan) in Ifriqiya (present-day Tunisia). These new cities drew Jewish residents as well, and seeded the Middle East with newly-established communities that would eventually come into their own, curtailing the power of the Geonim.

Reads & Resources

Most treatments of Jewish life in early medieval Eretz Yisrael are in specialty publications or hard-to-find books. The chapter by Shmuel Safrai in A History of the Jewish People, ed. H. H. Ben-Sasson, covers this period. For the period after (and including) the Muslim conquest, there is Moshe Gil’s A History of Palestine, 634–1099, translated from the Hebrew.

An excellent book on the difficult topic of theological anti-Judaism is Rosemary Ruether’s Faith and Fratricide: The Theological Roots of Anti-Semitism (1974; reprint, 1996). A more recent treatment is found in the early chapters of David Nirenberg’s powerful Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition.

For a general history of the late Roman Empire and the establishment of the Byzantine Empire, I’m currently reading and really enjoying the last three books in this series from Harvard University Press. (They’re displayed out of order; the last three are The Triumph of Empire, The Tragedy of Empire, and New Rome.)

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective.

I thank Yisrael Dubitsky for finding the manuscript source, which is misquoted in much of the scholarly literature, and bringing this to my attention.