The Safed Circle I: R. Yosef Karo and R. Yaakov Beirav

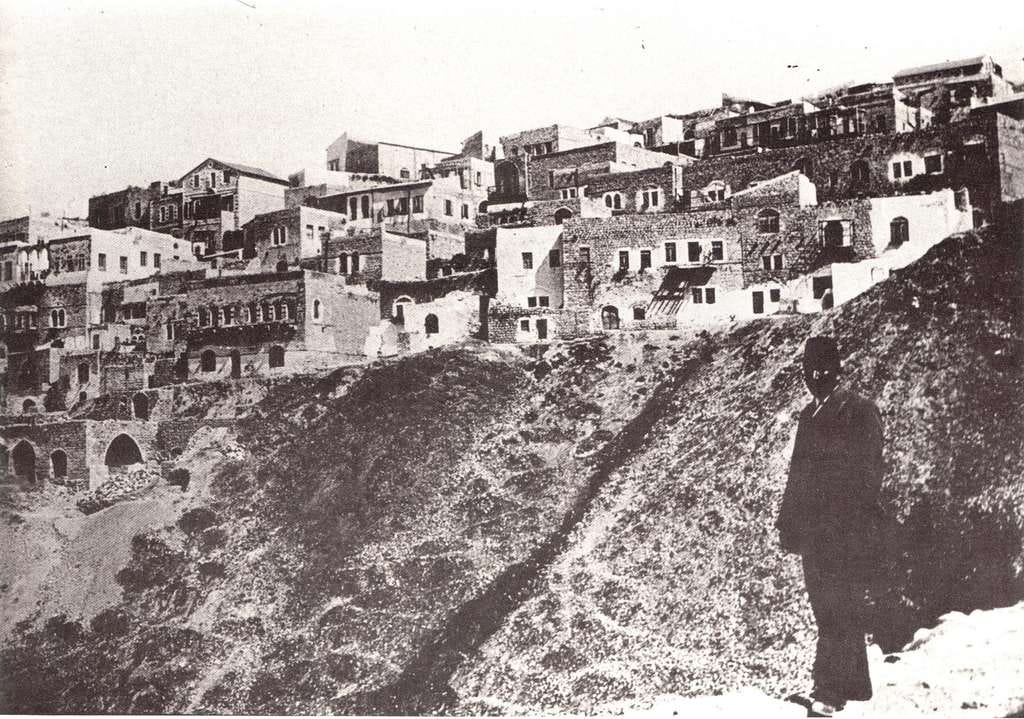

🧿 In the hillside town of Tzfat (Safed) in the Ottoman-ruled Land of Israel, victims of expulsions from Europe found space for Kabbalistic creativity and even the reinstatement of formal ordination.

Audio (Paid Feature)

Find an audio version of today’s newsletter here.

In this issue:

It was in the northern Galil town of Tzfat (Safed) that the Jewish Middle Ages became recognizably modern, with Kabbala serving as a site of both continuity and transition. There are vigorous debates about when, where, and how Jewish modernity was birthed. Some favor 1492, the year of the massive and traumatic expulsion from the relatively recently-united kingdom of Castille-Aragon. This is the earliest demarcation point. The latest is the political emancipation of European Jews, generally the early, French emancipation edicts of 1790-91. Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), who lived after his excommunication from the Portuguese Jewish community of Amsterdam as an unaffiliated person, has been called the first modern Jew. What this debate shows us is that the set of mentalities and socioeconomic forces we recognize as the beginning of our own era developed over a protracted period, which historians have come to call early modernity, roughly 1450 or 1500 to around 1800. But perhaps nowhere more than Tzfat do we see these forces mix, meld, and give shape to the world-to-come, even as they build firmly upon earlier foundations.

The Growth of the Tzfat Jewish Community

Tzfat, historically one of four especially holy Jewish communities in the Land of Israel along with Jerusalem, Chevron (Hebron), and Tverya (Tiberias), was brought to life economically by its position as a regional center in the new Ottoman empire. The Islamized Ottoman Turks had burst onto the historical scene in the fourteenth century and in short order, by the middle of the fifteenth, united much of the Levant and Turkey into a well-administered and powerful empire. The difficult economic circumstances in Jerusalem prompted many Jews, and particularly Sefardi exiles, who wished to live in the Land of Israel, to settle in Tzfat. There they joined, as in other parts of the Ottoman empire, congregations of Jews separated by place of origin, including Sefardi, Ashkenazi, Maghribi (from northwest Africa), and more. They brought with them not only disparate traditions, customs, and languages, but also a deep interest in Kabbala as a tool for finding meaning in Jewish texts, rituals, and history.

R. Yosef Karo’s Mystical Activities

Known to Sefardim as, simply, Maran—our teacher and rabbi—and to Ashkenazim as the Mechaber, the compiler, R. Yosef Karo was famed for his definitive code of Jewish law, the Shulchan Aruch. This code built upon his brilliant precis of previous law going from the Tannaim, the early sages, up through the Rishonim and his own time, called the Beit Yosef (and styled as a commentary on the fourteenth-century code of R. Yaakov Ben Asher, the Arbaa Turim). In 1570 in Krakow, Poland, the Shulchan Aruch was first published with the glosses of the Rema (R. Moshe Isserles), adding Ashkenazi practice to the Mechaber’s Sefardi masora (the Shulchan Aruch itself, without the glosses, was first printed in Venice in 1565/6, a few years after its writing). This allowed the code to be adopted across the Jewish world and become definitive, although the process arguably took place over the following century. This made R. Yosef Karo enormously influential. It also designated those rabbis following the Shulchan Aruch “Acharonim,” or latter authorities.

Born in Spain, probably Toledo but possibly after the family had left for Portugal, R. Yosef Karo was a young child at the time of the expulsions. After the Portuguese expulsion of 1497, the Karo family fled to Ottoman Turkey, where the Mechaber spent about the next forty years of his life, before making aliyah to the Land of Israel. I wrote about the Mechaber's life here:

In addition to his dazzling prowess as a halachist, R. Karo was a devoted mystic. Kabbala only occasionally effects his mainline psak (legal decisions), but it deeply influenced the course of his life and impacted his thought profoundly. His seeking of communion with G-d, personal experience of Divine closeness, and interest in ascetic practices are captured in this passage from his mystical “diary,” the Magid Mesharim:

אור ליום שבת כ"ז לאייר בפרשת מדבר סיני אכלתי מעט מזעיר וכן עשיתי בשתייתן, ושניתי משניות בתחילת הלילה וישנתי עד אור היום והקצתי והשמש זרח על הארץ, ונצטערתי מאד באמרי איך לא קמתי בעוד לילה כדי שיבא אלי הדבור כמנהג, ועם כל זה התחלתי לגרוס משניות וקריתי ה' פרקים, ובעודי קורא במשניות קול דודי דופק בתוך פי מנגן מאליו והתחיל ואמר: ה' עמך בכל אשר תלך וכל אשר עשית ואשר תעשה ה' מצליח בידך, רק כי תדבק בי וביראתי ובתורתי ובמשניותי תמיד, ולא כאשר עשית בזאת הלילה שאף ע"פ שקדשת עצמך במאכלך ובמשתייך מ"מ ישנת שנת עצל, כי הדלת תסוב על צירה והעצל על מטתו, ולא קמת לקראות המשניות כמנהגך הטוב, ועל זה היה ראוי לעזבך ולנטשך אחרי שנתת תוקף לסמאל ונחש ויצה"ר בשינתך שישנת עד שהאיר היום. אבל בזכות השיתא סדרי משנה שאתה יודע על פה, ובזכות אותם העינויים והסגופים שעשית בימים שקדמו וגם עתה אתה מחזיק בהם, הסכימו בישיבה של מעלה שאחזור לדבר עמך כבראשונה ושלא אעזבך ולא אנטשך.

On the nightfall of Shabbat, the 27th of Iyar, on which Parashat Midbar Sinai was read, I ate a small amount and so also with regard to drinking. I studied Mishnayot at the beginning of the night and slept until the light of day. When I awoke the sun was shining upon the land, and I was deeply remorseful in saying to myself, How did I not arise while it was still night so that the speech would come to me as it usually did? With this I began reviewing Mishnayot and read five chapters, and while I was still reading the Mishnayot, the voice of my Beloved knocked (kol dodi dofek) within my mouth, ringing out. It began, saying, ‘Hashem is with you everywhere you go and in all that you have done and will do Hashem will cause you to succeed, as long as you cleave to Me and to awe of Me and to my Torah and Mishnah always, not as you did this past night. For even though you make kiddush over your food and drink, you slept the sleep of the idle, just as the door turns on its hinges does a lazy man turn in his bed [based on Mishlei 26:14]. You did not arise to read the Mishnayot as is your good practice, and for this I should have left and abandoned you, since you gave power to Samael and the serpent and the evil inclination, through the sleep that you enjoyed until the light of day. But due to the merits of the six orders of Mishna that you know by heart, and by the merit of the deep study and self-abnegation that you undertook in the previous days and even now hold to, it was agreed in the Yeshiva of the heavens that I should come and speak to you as I had before, and that I should not leave or abandon you.

Magid Mesharim, Introduction

The Mechaber, as well as being an immense scholar of the law, here shows himself to be a person of intense spiritual striving. His learning is animated by personal urgency and deep emotion; failure to withstand physical deprivation in order to memorize the Mishna is not only a moral failing but one that actually brings evil into being.

In what would become characteristic of Safedian circles, and building upon late thirteenth century models of mystical fellowship, the Mechaber also developed around him in Turkey and especially in Tzfat a group of Kabbalists who strived together to achieve mystical insight, craft and undertake practices appropriate to Eretz Yisrael, and help to bring about the messianic era.

The Semicha Controversy with R. Yaakov Beirav

Among R. Karo’s associates, and probably teacher, was R. Yaakov Beirav (c. 1474–1546), a preeminent halachist, Kabbalist, and mentor to many disciples. Like R. Karo, R. Beirav had been born near Toledo and fled Castille in 1492 upon the order of expulsion there, settling in Fez, Morocco, where he was apparently appointed rabbi at a young age. This gave him a large degree of confidence in his powers to make halachic decisions, which was to rankle some. Business affairs took R. Beirav to Egypt, Syria, and the Land of Israel, and he was in Tzfat off and on beginning in 1524.

As part of his bid to encourage the coming of the messiah—R. Beirav saw the upheavals of the Iberian expulsions as indications of the beginning of the messianic era—he decided to reinstitute the practice of authentic semicha, the physical laying-on of hands that indicated rabbinic authority based on a line of impeccable transmission. The institution has its basis in the Torah, when Moshe places his hands upon Yehoshua to indicate a transfer of authority to him as well as the authentic transmission of the Mesora, the Oral law. The unbroken line of true semicha was thought to have ended during the period of Chazal (the sages of the Talmud), to be revived only in the messianic era. As such, an attempt to revive it was a bold statement that this hoped-for era had arrived.

This was a step that the bold R. Yaakov Beirav persuaded his circle in Tzfat to take. A group of rabbis went forward and reinstated semicha, with R. Beirav being the first one so ordained. Immediately, the great halachic authority of Jerusalem, R. Levi Ibn Habib, was notified. R. Ibn Habib, however, had already held several disputes with R. Beirav on various halachic matters, and he was seriously disinclined to acquiesce. He refused to accept R. Beirav’s semicha and the whole enterprise.

During this contentious back-and-forth, R. Beirav became entangled in a local matter of dispute and was denounced to the Ottoman authorities. Forced to flee the Land of Israel for Damascus, the entire semicha project seemed fated to die with him, since he was the only musmach (ordained) and semicha could only be conferred in Israel. Hurriedly, R. Beirav gave semicha to four among his circle, including R. Yosef Karo (as well as Mabit, R. Moshe di Trani, known as a profound kabbalist).

R. Ibn Habib, angered by this public flouting of his concerns, enlisted the support of others, including the great Radbaz (R. David Ibn Avi Zimra, 1479–1573), another Sefardi exile who had settled in Egypt and become a preeminent scholar there. Notably, unlike R. Ibn Habib, Radbaz was himself a deeply committed kabbalist. His kabbalistic views, however, were not messianic in the same way as R. Karo's circle’s in Tzfat. R. Ibn Habib ultimately captured his perspective on the semicha controversy in a multi-part essay titled Kuntres ha-Semicha.