Coffee with Ibn Ezra

☕ Our anachronistic coffee date this week is with that inimitable, hilariously acerbic, and achingly brilliant polymath: Avraham Ibn Ezra.

Hello new subscribers, and welcome back, friends.

First, a quick bit of housekeeping: You might have heard </sarcasm>, Twitter is imploding. It seems to have taken Revue, my erstwhile newsletter provider, with it. So I switched to Substack. (Should have started here, tbh, but I signed up with Revue on a whim since it was integrated with Twitter. Ha.) Anyway, same nerdy Jewish content, slightly different platform. Silver lining: Substack makes it easier to leave comments and interact. Drop me a line below or hit reply.

Okay, let’s go hang out with Ibn Ezra. Below:

Ibn Ezra Introduces Himself

His love of language, dark humor, penchant for astrology, personal bitterness, and dour personality, it’s all here in this four-line poem:

גַּלְגַּל וּמַזָּלוֹת בְּמַעְמָדָם / נָטוּ בְּמַהְלָכָם לְמוֹלַדְתִּי | לוּ יִהְיוּ נֵרוֹת סְחוֹרָתִי – / לֹא-יֶחֱשַׁךְ שֶׁמֶשׁ עֲדֵי מוֹתִי | אִיגַע לְהַצְלִיחַ וְלֹא-אוּכַל / כִּי עִוְּתוּנִי כּוֹכְבֵי שָׁמָי | לוּ אֶהֱיֶה סֹחֵר בְּתַכְרִיכִין– / לֹא יִגְוְעוּן אִישִׁים בְּכָל יָמָי

The spheres and constellations in their configuration / tilted wayward in their path at the time of my birth. Were my trade in candles / the sun would never set till I died. I weary myself trying to succeed and can’t / since the stars above lead me astray. Were I a merchant of shrouds, nobody would die my whole life long.

גלגל ומצלות (בלי מזל)

Rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra was born in Tudela, Spain in 1089.1 For the first fifty years or so of his life, he never left the orbit of the Muslim world, and wouldn’t have wanted to; for the elites of glittering Sefarad, Christian Europe was an uncultured hinterland.

But even back home in Spain, Ibn Ezra was a square peg. Despite having an upper-cust education, he couldn’t quite hack it in one of the gentlemanly occupations of the day: physician, dayan (rabbinic judge), merchant, courtier. The life of a writer and educator was a viable, if unstable, career path. (Do I overrelate? Maybe.) Among the Judeo-Arabic intelligentsia, poetry wasn’t just for prestigious, unthumbed literary periodicals. It was a vital part of social life, like having a killer bio and a well-opened newsletter (ahem). People actually hired poets to write fancy letters, panegyrics, and overwrought eulogies for them.

Ibn Ezra was one of those poets. In want of patronage, he wandered from Tudela in the north to Córdoba, the New York of its day, then to Seville, where he raised his son, to Toledo, one of the earliest Muslim territories to fall to Christian forces, in 1085. (Ibn Ezra referred to it as Edom, identified in premodern Jewish ethnography with Christendom.) He also traveled through the Maghrib (northwestern Africa, encompassing what is today Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya), home to populous Jewish communities. Among his poems are many piyutim (liturgical poetry), some of which survive in various nuschaot (prayer rites).

It couldn’t have been easy to have the celebrated, successful Rabbi Yehudah ha-Levi as his close friend and relative by marriage—Ibn Ezra’s son Yitzchak married Yehudah ha-Levi’s daughter. In his own way, which we’ll have to explore in another newsletter, Yehudah ha-Levi fit uneasily into the society of which he became such an exemplar. But ha-Levi was much more well-heeled, well-liked, and prosperous than Ibn Ezra. And then, when ha-Levi set sail for Eretz Yisrael, Yitzchak went with him. Though the evidence isn’t ironclad, it seems that Yitzchak Ibn Ezra then made his way to Bavel (Iraq), eventually converting to Islam. The stars, as Ibn Ezra would have said, aligned against him.

The Misfit Who Won the West (of Europe)

The 1140s were rough in Muslim Spain. Political upheavals and increasing intolerance towards religious minorities by Berber Muslim dynasties impelled many Jews to seek new homes. These reluctant emigres became tradents of Judeo-Arabic culture, with its love of belles-lettres (adab), rationalist philosophy, and halachic codification. Ibn Ezra became, along with the Kimchis (as in Radak) and the Ibn Tibbons (the dynasty of Arabic-to-Hebrew translators), a primary vector of this cultural transmission.

Ibn Ezra first went to Rome. No one needed to hire a poet in Italy (the first buds of humanism wouldn’t blossom for some time yet), so Ibn Ezra took to tutoring the sons of the wealthy, primarily in Tanach. At their behest, he wrote down his lessons as commentaries. Ibn Ezra brought with him a generations-old Sefardi tradition of grammatical Bible commentary. Because Arabic and Hebrew are cognate languages, and Islamic culture places such high value on linguistic knowledge, Jews living in the Islamicate world made many philological discoveries that advanced their understanding of Hebrew. Most of the grammatical glosses on Tanach produced by Sefardi Jews have been lost to history, traces of them surviving, however, in Ibn Ezra’s Hebrew commentaries.

Ibn Ezra kept moving, you’re-only-as-good-as-your-last-picture style, first in Italy, to Lucca, Pisa, Verona, and Mantua, then through Provence (Béziers, Narbonne). He seems to have left his commentaries behind with his patrons (who’d paid for them), rewriting them twice, sometimes three times for new students. This is how we get the standard (“short”) Torah commentary alongside the “long” one.

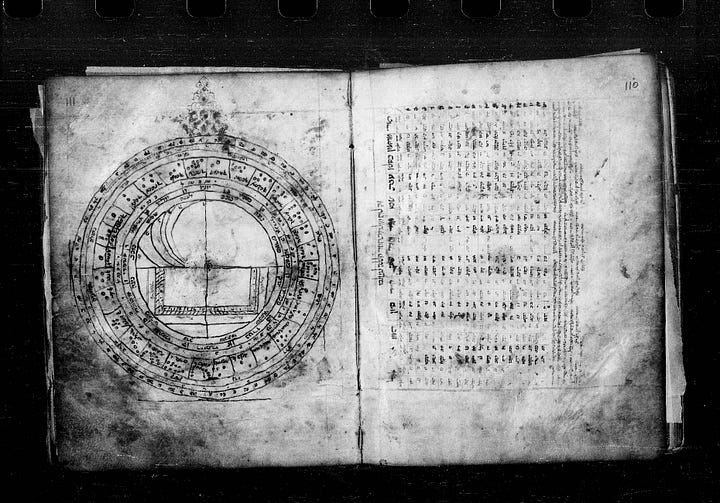

Ibn Ezra also began accepting commissions to write and translate into Hebrew dozens of works of philosophy, grammar, science, calendrication, and applied astrology. (Yes, this means he made actual star charts, a.k. a. horoscopes, for people, some of which survive in manuscript.)

An Unlikely Ending

Towards the end of his life, Ibn Ezra made his way to Rouen in Normandy and then, though the evidence is inconclusive, probably to its satellite community in England. This was literally the ends of the Jewish world, and I shudder to think of him walking the banks of the Thames in a thick, frigid fog, so very far from sun-drenched Spain, perhaps feeling forgotten. (Don’t worry, he wasn’t.)

There are many legends about the place of Ibn Ezra’s death, c. 1164. My favorite places him back home, in his grudgingly beloved al-Andalus, though it’s fanciful and almost certainly untrue. The most colorful comes from the prickly Rabbi Moshe Taku, another medieval true original, who, about a century later, suggests that the deep believer in the powers of human reason was felled by…demons:

והנה אבן עזרא כתב בספרו ‘ודאי אין שד בעולם’… והנה אבן עזרא טעה בשדים שהיו מלוין אותו תמיד… ואף על פי כן שדים הראו לו שישנם בעולם. ושמעתי מבני איגלאנט, ששם מת ביניהם, כי פעם אחת היה רוכב ביער ובא בין רוב כלבים שהיו עומדים ומעיינים עליו, וכולם שחורים. ודאי אלו הם שדים. כשיצא מביניהם אז נסתכן וחלה ומת מאותו חולי.

Here, Ibn Ezra wrote in his book, “there is certainly no demon in the world” and yet Ibn Ezra was mistaken about the demons that were always accompanying him…and even so, demons showed him that they are present in the world. I heard from people of England that there he died among them, when once he was riding in the forest and came upon a pack of dogs that were standing and threatening him, all of them black. Certainly these were demons. When he went out among them, then he was endangered, and became ill and died of that same illness.

Moshe Taku, Ketav Tamim

Ibn Ezra soon came to sit opposite Rashi on the pages of Tanach, representing the great exegetical heritage of Sefarad in counterpoint to Rashi’s midrash-steeped Ashkenazi style. Today, it is usually in Ibn Ezra’s Bible commentaries that we encounter his philosophical and grammatical insights and his wacky ideas about brain function, numerology, and astral influence. We watch him fell his intellectual interlocuters with sardonic panache, convince us with his brilliance, and, when we’re lucky, stumble upon a great secret (sod) which, he says pointedly, he’ll merely hint to us, and if we’re smart, we’ll keep quiet about it.

These secrets for me are the distance between between our postmodern subjectivity and his medieval confidence in the ability of reason to uncover truth. I have no doubt that Ibn Ezra had an actual secret in mind, and I want to know it. In the way that only timeless ideas can, his end up speaking to the present. Ibn Ezra’s secrets force me to jettison my desire to know and, instead, to live with the idea that there is an answer, just one that is inaccessible right now. Still, it’s out there.

Ibn Ezra Reads

The book on Ibn Ezra still waits to be written. In its stead, though it’s an academic volume (fair warning), I can heartily recommend Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra: Studies in the Writings of a Twelfth-Century Jewish Polymath, edited by Isadore Twersky and Jay M. Harris (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993), which is freely available on academia.edu.

Ibn Ezra on Sefaria includes his Tanach commentary, Yesod Mora (his main philosophical work), and Iggeret ha-Shabbat (though the attribution, especially of the poem, is fraught with questions).

To get a flavor of the world from which Ibn Ezra came, as well as many beautiful renderings of his poems, get The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950-1492 by Peter Cole, himself a poet (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007).

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

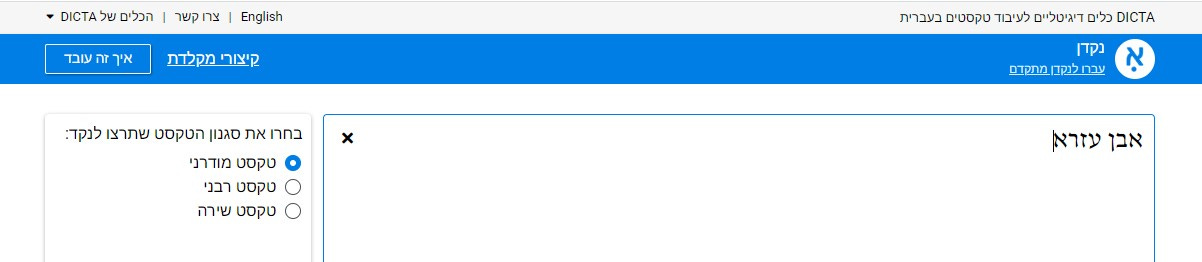

Dicta makes an assortment of useful digital tools for text study, and I’ll probably get through all of them. Today I want to highlight their Nakdan, a tool for adding vowels to Hebrew words. Vocalization is a science and a challenging one to master, so even to use even their simple, automatic tool requires a fair amount of grammatical knowledge. Still, a great tool to know about. (Above, you can see how it handles Ibn Ezra.)

Ibn Ezra Twitter Threads

ICYMI - my Sunday threads about Ibn Ezra are below. The first is a general intro; the second is about his philosophical predilections, and why his outdated science still matters. (You don’t need a Twitter account to view them.)

Next week

Next time, we're having anachronistic coffee with Ibn Ezra's (probable) interlocutor and Rashi's opinionated grandson, Rashbam.

Historians prefer the term Iberia to Spain because it more accurately captures the diversity of regional cultures, languages, and polities that existed before the rise of the modern states of Spain and Portugal. I’m using Spain because that’s what most people think of where academics pedantically insist (guilty, btw) on “Iberian peninsula.” But it’s helpful to know that a Galego speaker in, say, 1200, would have had as little in common with a Castilian speaker as does a speaker of standard French today. They were in real ways different countries. (Contemporary Catalan politics have got nothing on the Middle Ages.)

Would be an awesome person to have coffee with! I'd always assumed that Ibn Ezra also visited India, but this post pushed me to dig a bit deeper and discover that references to Indian in his works are perhaps second hand... Have always found it fascinating that Ibn Ezra may have been the first to introduce the decimal system to Europe.