Coffee with Rambam

☕Rambam (Maimonides) reconfigured halacha and clarified its underlying theory, insisted on the significance of human reason while reaching for the sublime—all as a displaced political refugee.

Happy medieval Tuesday. NBD, today we're hanging out with the rabbi who changed everything, forever—a once-in-a-millennium mind. To capture the essence of Rambam’s genius and influence in an introductory piece, especially in light of the unusually rich medieval evidence we have of his life, is daunting. I recently contributed a chapter about the innovative nature of Rambam’s thought to a forthcoming book, and getting it down to 5000 words was…challenging. But we’re going to press forward, with the caveat that this newsletter is going to aim to be a useful overview of Rambam’s eventful life and an entry point to his robust, world-changing oeuvre.

In this issue:

Will the Real Rambam Please Stand Up?

Rambam contains multitudes. He’s extra good at refracting back whatever it is that his reader wishes him to be. Was Rambam an iconoclast who pushed the envelope? A conservatively-minded traditionalist? Consummate rationalist and radical Aristotelian—or secret Kabbalist? That depends on who wants to know, and which Rambam you open, and, probably, your innermost sense of Truth. Many individuals and communities have determined who they consider to be the real Rambam, but other Rambams persist in showing up. There is the Rambam of the letters, where he often shows himself to be more empathic and flexible than the stern Rambam of Mishneh Torah; Rambam the codifier, enclosed in the dalet amot of the halacha vs. Rambam the philosopher, open to new currents of Greco-Islamic thought; the same Rambam who put off starting a family and the one who doted on the young son of his old age, and on his like-a-son student, whose departure left him bereft. These Rambams are all here before us, asking to be known, to be taken into account. We cannot begin to understand his Torah without the full complexity of the Great Eagle, as he came to be known, or, more commonly among his contemporaries, simple “the Rav” or “Rabbi Moshe.”

Early Life in Córdoba, Spain

His whole life, Rambam signed his name as ha-Sefaradi, “the Spaniard.” This, even though he built his life, becoming essentially a celebrity, in Egypt. Those formative early years, coupled with the proud self-perception of Sefardi Jewry, imbued in him a deep sense of Andalusi cultural identity. The family’s flight from Spain (more on that in a second) was not only a personal hardship but a cultural displacement of the type Dr. David A. Wacks has termed “double diaspora”—the sense of being doubly exiled, first from the Land of Israel but also from the robust, distinctive culture that characterized the Jewish life in al-Andalus (Muslim Spain).

Rambam’s father, Maimon, was a dayan, a judge in the rabbinical court of Córdoba. He had been educated at the famed yeshiva of Lucena, where we last saw the Rif; his son Moshe considered his scholarly lineage, too, to be of Ri Migash and Rif, though he was too young to have studied under them himself. There is scholarly debate about the date of Rambam’s birth as well as the date that the family fled; this makes a substantive difference because it determines at what age Rambam left Sefarad and how much cultural exposure he had as a young person. To the best of our knowledge, he was born around 1135 (I personally tend towards the arguments in favor of 1138 as his birth year) and left Spain around 1159. This would mean that, at minimum, Rambam received the fruits of a full Andalusi education and could well have expected to live a quiet, meaningful life of scholarship and service in the mold of his father before him. But that’s not what happened.

Coming of Age in Almohad Fez

The political unity of al-Andalus had worn down well before Rambam’s time, but the defeat of the strict Almoravids by the extremist Almohads, another Berber Muslim dynasty, in 1147 brought yet more turmoil and intolerant policies towards the Jews of Spain.1 Like so many others, the Maimon family fled the political instability and religious intolerance. Curiously, they went to Fez, which was, so to speak, the lion's den: the Almohad capital.

It is not entirely clear why the family settled there for a time. It may have been as simple as having personal connections there. The Muslim historiographer Ibn al-Qifti, a younger contemporary of Rambam’s, claimed that Rambam had been converted to Islam. Apart from this claim, which of course comes with its own perspective, the evidence is conjectural. Regardless, Dr. Sarah Stroumsa has argued that Rambam's coming-of-age years under Almohad rule left their mark upon the young scholar. We certainly see Rambam's compassion for forced converts to Islam in his responsa and his unusually sensitive treatment of the problems, including theological ones, entailed by the political climate. While in Fez, Rambam trained as a physician and began writing his Commentary on the Mishnah, in which he sought the root legal sources of the Oral Torah.

The Eagle has Landed in Egypt

Around 1166, when Rambam was nearing thirty, the family made a final move to Fustat (Old Cairo) in Egypt. By the time he arrived in town, Rambam was renowned enough to attract attention and be pressed into communal service, especially with regards to challenging legal matters. He soon found a marriage match from among the elite local families, which considerably improved his social standing, especially as a self-conscious outsider. Rambam was initially supported by his beloved brother David, a successful merchant, and had much time to devote to scholarship. After completing the Commentary on the Mishnah, he wrote Sefer ha-Mitzvot, which systematically enumerated the Torah commandments. This would form the backbone of his great legal code, the Mishneh Torah.

In 1177, disaster again struck the family: David was drowned in a merchant ship in the Indian Ocean. Years later, Rambam would write in a letter,

ואחר כך עד היום, כמו שמונה שנים, אני מתאבל ולא התנחמתיץ ובמה אתנחם…והלך לחיי עולם, והניחני בארץ נכריה. כל עת שאראה כתב ידו או ספר מספריו יהפך עלי לבי ויערו יגוני

“Close to eight years have now elapsed and I still mourn for him, for there can be no consolation…He has departed to his eternal life and left me confounded in a strange land. Whenever I come across his handwriting in one of his books my heart turns within me and my grief reawakens.”2

Rambam, Letter to Yefet ha-Dayan

In addition to his personal grief, Rambam was pressed into service as financial support for the extended family. This meant the he took a position as court physician, at which he labored for long hours in his old age. It was then, however, that Rambam gave the world a final gift: Moreh ha-Nevuchim, “The Guide of the Perplexed,” written for his student, whom he regarded as a son, and the others like him, however few, whose minds were bedeviled by philosophical questions. Translated into Hebrew in 1204, the year of Rambam’s death, it remains the most important philosophical book in Jewish history.

Thus we have the folk saying, written as an epitaph on the traditional site of Moses Maimonides (Rambam)’s grave: “From Moses to Moses, there was none like Moses.”3

Rambam Reads

We’re blessed with a plethora of resources about Rambam, including a number of biographies in English. Each is valuable in its own way, but I can’t recommend Moshe Halbertal’s Maimonides: Life and Thought enough: it’s beautifully organized, up-to-date with the latest research, comprehensive but approachable, and just a great read.

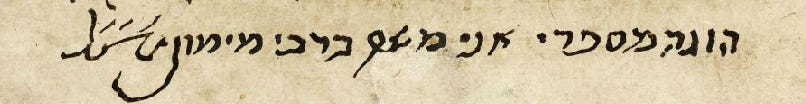

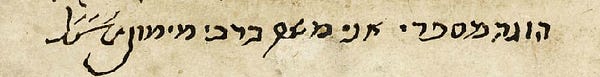

This detailed blog post from the British Library about their autograph teshuva has lots of juicy manuscript images; it’s a guided tour through this invaluable Geniza document.

On the Main Line (one of the OG Jewish bloggers - hi @onthemainline!) has an epic post about the autograph copy of the Mishneh Torah.

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

Amazingly, Kehati, the clear-as-day contemporary commentary on the Mishnah, is available as a free app (it even has a beautiful UX). The app features the Mishnayot with Kehati in Hebrew and English, as well as Bartenura. It includes Kehati’s helpful introductions to each masechet as well.

Download Kehati from Play Store | Download from App Store

Rambam on Twitter

ICYMI!

Next Week

We’re off to Provence to spend some quality time with the very impressive, very charif (spicy, intense) Raavad.

Both of these terms are Spanish approximations; the Arabic for Almohads tells more of the story: al-Muwahhidun, a cognate of the Hebrew המאחדים, “the Unifiers,” a reference to their theological stance.

Letter to Yefet ha-Dayan, in Shailat, ed., Letters, 1:228-230; cited in Moshe Halbertal, Maimonides, 59-60, in the translation of L. Sitskin, Letters of Maimonides (New York: Yeshiva University Press, 1977), 73.

The earliest record of the saying is found in the introduction to the thirteenth-century Sha’ar ha-Shamayim by R. Yitzchak Ibn Latif, a philosophical commentary on Kohelet, which has been published in a critical edition by Raphael Cohen (Jerusalem: Magnes, 2015). The earliest record of Tiberias, Israel as the burial place of Maimonides is in Ibn al-Qifti (thirteenth century).

Do we know if David was younger or older than RMBM?