Coffee with Raavad

☕The acerbic critic, for all his renown, is yet underappreciated for his contribution to the conceptual study of halacha. Yes, there are some icy hassagot selected for you, but so much more!

Hello, friends, and welcome (back) to Stories from Jewish History, the newsletter that takes you into the never-uneventful Middle Ages for some quality time with your favorite Rishonim (medieval Torah scholars).

Today we’re on the leafy campus of Raavad’s yeshiva in the town of Posquières, today’s hole-in-the-wall Vauvert in southern France. Raavad is known for his acerbic criticisms of Rambam (his younger contemporary), among others, plunging us straight into the debates at the heart of the proverbial smithy of Judaism’s soul. But he is scarcely characterized by his critical glosses alone; Raavad is a figure of such brilliance, it’s particularly important to pause and take in his manifold intellectual contributions—some of which await modern editions and further study.

In this issue:

Made in Provence

Raavad was both shaped by medieval Provençal Jewish culture and a major influence on its trajectory. What Jews have traditionally called “Provence” refers to the whole swathe of land between the Pyrenees and Italy, approximately the southern third of present-day France, which in the Middle Ages was distinguished linguistically.1 I’ll try not to wax too poetic here, but I’m a little obsessed with medieval Provence (my dissertation dealt with major aspects of its culture) and here’s why: it sits at the crossroads of Europe and has its own unique culture infused with both Ashkenazi and Sefardi ideas. For example, in the twelfth century when Raavad lived, Jewish Provence was a hotbed of Kabbalistic thought even as it was nurturing the beginnings of what would become a proud rationalist philosophical tradition—all the while steeped in distinctive traditions of Torah scholarship made famous in the academies of Narbonne, Lunel, and Béziers.

Though legend places the beginnings of Provençal Jewry in the ninth century at the time of Louis the Pious, son of the great Frankish King Charlemagne, we do not begin to see it flowering until the eleventh century. By the time of Raavad’s birth, c. 1125, Provence had a well-developed culture of learning. His primary teacher, R. Meshullam ben Yaakov of Lunel, sat at the helm of the famed Lunel yeshiva and seeded Provence with scholars, including his own five sons. R. Meshullam was primarily renowned as a posek (legal scholar) but also displayed notable openness to science and philosophy. Another of Raavad’s great teachers, Rabi Abad (R. Avraham ben Yitzchak, Av Beit Din of Narbonne), who also became his father-in-law, author of the Sefer ha-Eshkol, the earliest Provençal halachic work and an important model for subsequent halachic treatises and codes, including Raavad’s.

Raavad’s Halachic Works

It was R. Meshullam who prompted Raavad to write his first treatment of a halachic subject, which resulted in Isur Mashehu on the nullification of the forbidden in mixtures, an area of the laws of kashrut. Raavad would go on to write several more such works which dealt in-depth with discrete areas of halacha, including the laws of lulav, power of attorney, and niddah (laws of family purity). Of these, the latter, called Baalei ha-Nefesh, has entered the mainstream yeshiva curriculum, while the rest remain the province of scholars.

This is the type of situation that immediately intrigues me. Of course, habent sua fata libelli: “books have their own destinies,” in the absolutely brilliant phrasing of Latin rhetorician Terentianus. That is, sometimes things just happen, and one book falls into disuse as another wins a spot on the bestseller list. But I still want to ask Why, and What If? What treasures lie in wait for us inside these lesser-known masterpieces?

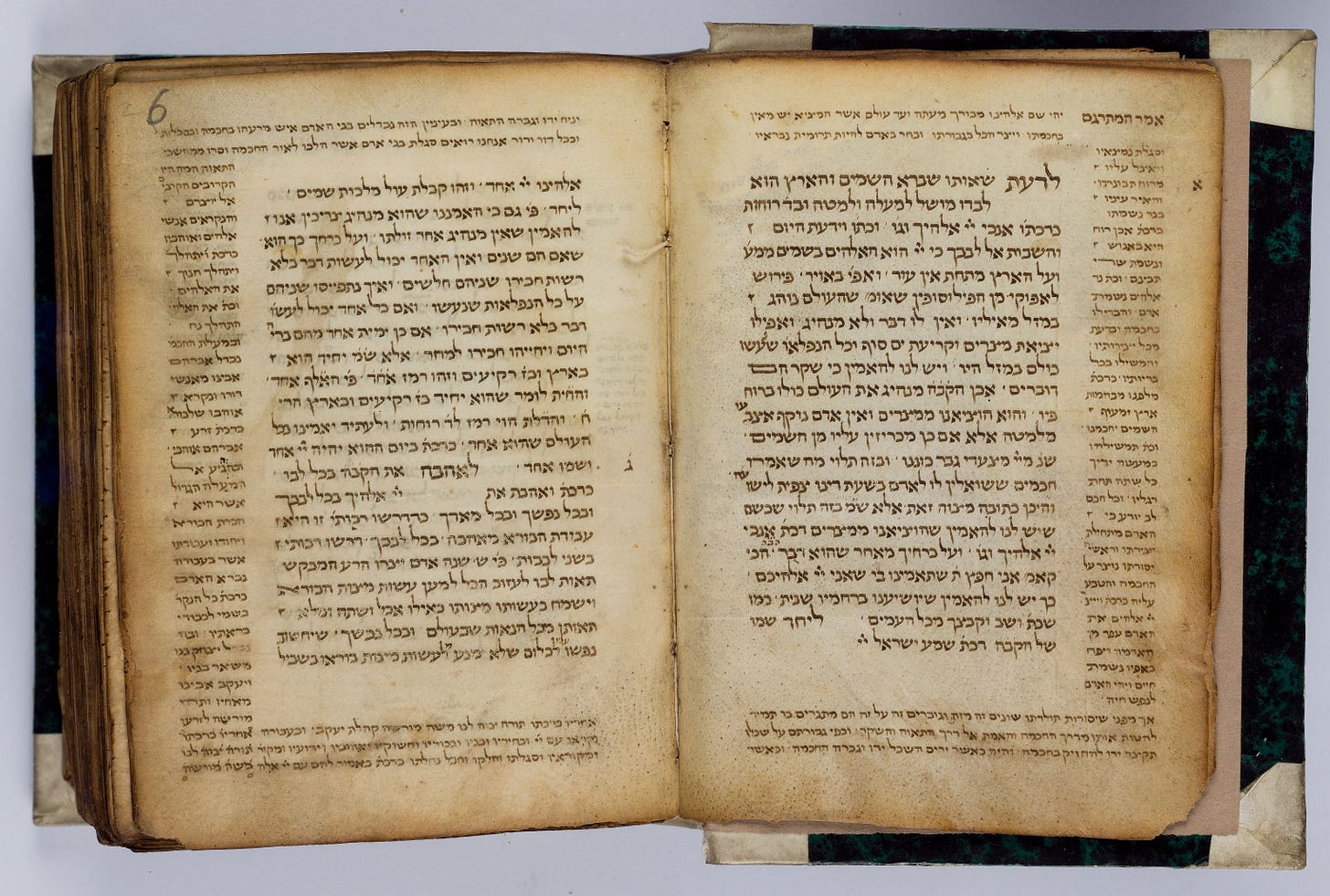

This is all the more true of Raavad’s writing on the Talmud. In the centuries following his death, Raavad became renowned as a master commentator, with R. Menachem ha-Meiri and R. Chasdai Crescas intimating that he wrote a commentary on the entire Talmud. In fact, it seems that Raavad’s Mishnah commentaries, which he wrote on the sections of the Mishnah for which there is no Gemara (Talmudic commentary), were written in completion of this larger project. (However, his work on the Mishnah was also among the first of its kind and heralded later direct commentaries on the Mishnah.) Today, we have as complete commentaries only those that Raavad wrote on Bava Kama and Avoda Zara, as well as partial commentaries, including sections cited in Shita Mekubetzet, the anthological commentary of the great sixteenth-century bibliophile and manuscript hunter R. Betzalel Ashkenazi.

From what we have, it’s clear that Raavad was a conceptual thinker interested in higher-order questions of halachic method. This also led him to write commentaries on the major halachic Midrashim, of which only the one on Sifra (on Vayikra) survives. Like the Tosafot, Raavad collates relevant passages from throughout the Talmud; his method is his own, however, subjecting the halachic subject to critical reading and distilling it down to its fundamental concepts.

So why didn’t Raavad’s Talmud Commentary and other writings survive in whole? In part, this seems to me a factor of his time and place, twelfth-century Provence. His commentary was ahead of its time; unlike those of Rashi in Ashkenaz and Rabbenu Chananel in Sefarad, which had spread widely by his time, his notes were not a comprehensive line-by-line commentary nor were they for beginners. At the same time, Raavad’s commentary was a little too early, unlike, say, ha-Meiri’s, whose huge Beit ha-Bechira on the Talmud managed to survive (though it fell out of circulation) from the thirteenth century, from which time period we begin to have more manuscripts. Finally, Raavad was in Provence, a community that would be dispersed and largely destroyed by the French General Expulsion of 1306 (and the subsequent French expulsions of the fourteenth century).

Raavad’s Hassagot (Critical Annotations)

I can’t let you go without a few words about Raavad’s (in)famous hassagot, which he wrote on Rif, then on R. Zerachia ha-Levi (Rezah) in defense of Rif (you read that right), and, of course, on Rambam. Since the first publication of Raavad’s Hassagot to Mishneh Torah in the sixteenth century, they have been a frequent accompaniment of Rambam’s code and the source of Raavad’s reputation as a fiery traditionalist. Take for example the gloss on Hilchot Talmud Torah 6, 14, which pertains to the part dealing with wrongful excommunication. First, Raavad seeks the source for Rambam’s ruling, objecting as he does throughout to Rambam’s opacity: “He extrapolated this matter from the case of Shimon ben Lakish who was guarding an orchard [in Moed Katan 17a].”2 Then, Raavad gives his opinion of the extrapolation: “On my life and mind! There is no great analysis here.”3 In another gloss, Raavad says of Rambam: “This comes out of the mess he made of these things, confusing these and those and likening in his mind matters that are discrete and entirely distinct.”4 His independence of mind is notable, but so too is the respect he gave to his younger contemporary by anticipating the magnitude of his impact and deciding to comment on his work.

Though Raavad himself wrote no Kabbalistic works, he was clearly at the center of early centers of Kabbalah that bubbled up prominently in Provence, in interesting and creative ways, in the twelfth century. Both of his sons, R. David and especially R. Yitzchak Sagi Nahor (an epithet meaning “the Blind”), were renowned Kabbalists whose thought and traditions were transmitted across the Pyrenees by the Geronese Kabbalists in the following century. Many later Kabbalists name Raavad as the source of their traditions, but he belongs yet to the generation in which mystical secrets were passed from teacher to disciple.

Raavad Reads

A number of Raavad’s works are available on Sefaria: the Hassagot on Mishneh Torah, Hassagot on the Rif, Katuv Sham (Hassagot on Baal ha-Maor), and the Commentary on Mishnah Eduyot. A small number of the Hassagot on Mishneh Torah are translated into English. Baalei ha-Nefesh is readily found in standard editions. A nice edition of Raavad’s Commentary on Avoda Zara, as well as the Chiddushim on Bava Kamma, the Commentary on Sifra, Isur Mashehu, Temim Deim, and the derasha for Rosh Hashana, are available from HebrewBooks.org.

R. Dr. Isadore (Yitzchak) Twersky’s book in English devoted to Raavad, Rabad of Posquieres: A Twelfth-century Talmudist (Harvard UP, 1962), remains a great read. Another excellent piece devoted to Raavad in English is R. Dr. Haym Soloveitchik’s essay, “Ravad of Posquières: A Programmatic Essay,” originally published in a 1980 festschrift (a book of essays published in honor of a scholar) and more recently republished in his Collected Essays III (Littman, 2020).

The Jewish Women’s Encyclopedia (JWA) has an entry on Raavad’s Baalei ha-Nefesh, which calls the work “one of the most important texts in the Jewish world concerning niddah and sexuality.”

To get a taste of Raavad’s theological stances, take a look at this article about corporeality (embodiedness) or this one about techiyat ha-metim (bodily resurrection), both in the Har Etzion website.

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

Bar Ilan University is in the process of publishing an amazing new edition of Mikraot Gedolot, based on Keter Aram Tzova (the Aleppo Codex) with critically edited texts of all the Mefarshim (commentators). It also has a companion website full of helpful material. In particular, it has a side-by-side edition of the Masoretic notes that is easy to consult if you’re tangling with a given pasuk.

Raavad on Twitter

Next Coffee

Next week we’re going to delve into the life of another great controversialist, Rabbenu Yonah Gerondi.

As in, people in the south spoke a family of languages, Occitan, not mutually intelligible to denizens of the north. Dante famously, in his linguistic treatise De Vulgari Eloquentia, divided the vernaculars of his age into groups by their word for “yes”: pays d’Oc (“countries that use oc,” i.e. Occitania/southern France/Provence), pays o’Oïl (“countries that use oui,” i.e. the Île-de-France, Normandy, and other northern regions), and pays de Sì (“countries that use sì,” Dante’s own Italy). The reason for the variance is that, weirdly, classical Latin doesn’t have a standard word for “yes,” such that each region used a different phrase as the basis for its “yes”: respectively, oc from hoc, “this”; oïl (today’s oui) from hoc illud, “this is it,” and sì from sic, meaning “so it is.” Today’s stam “French” is a descendant of northern French, while the Occitan languages are nearly extinct.

דבר זה הוציא ממעשה דריש לקיש דהוה מנטר פרדיסא וכו'.

ובחיי ראשי אין כאן פלפול

Gloss on Hilchot Teshuva 3:5.א''א זה מן הערבוב שמערבב הדברים זה בזה ומדמה בדעתו שהן אחדים והם זרים ונפרדים מאד

Amazing work!! Thanks so much.

This is an amazing bio - really brings him to life! You present him and his work so clearly and in such an interesting way. Thank you!