Coffee with Rabbenu Yonah

☕Sensitive, turbulent, unafraid but filled with deep humility, Rabbenu Yonah was the conscience of thirteenth-century Spain—and beyond.

Hello, friends. As always, thanks for all your comments, feedback, support, and, just in general, for being here with me as we journey through the world(s) of the Rishonim. Today we’re spending time with Rabbenu Yonah, known for his musar works as well as his commentaries on Mishlei and Pirkei Avot.

Inside this issue:

Rabbenu Yonah’s Musar (Ethical Works)

Rabbenu Yonah and his Students

Rabbenu Yonah ben Avraham Gerondi (of Girona) is known for two seemingly contradictory habits of mind: the zeal of his public activity and the sincerity of his piety. Often fêted with the appellation he-chasid, “the pious,” generally reserved in his period for the rare ascetic, mystic, or other such spiritually disciplined individual, Rabbenu Yonah reversed his own highly public criticisms of Rambam with great humility. At the same time, he was an advocate of involvement in public affairs, exhorting householders to greater religious observance and railing against rampant sexual impropriety.1

Born in Girona, in northeastern Spain, c. 1200, Rabbenu Yonah pursued a unique course of education. Despite his proud Sefardi lineage, a tradition in which he would largely work halachically, Rabbenu Yonah sought his education in France. He studied under the renowned Tosafists R. Shmuel (ha-Sar, “the Prince”) of Evreux and his brother R. Moshe. Rabbenu Yonah found his other primary teacher in R. Shlomo min ha-Har (of Montpellier), a respected Provençal posek (legal decisor) and controversialist—though, as we’ll see below, a somewhat inadvertent one. While in Provence, Rabbenu Yonah seems to have become involved in the currents of Kabbalah washing through the region, and had important correspondence with R. Yitzchak Sagi Nahor (“the Blind”), son of Raavad. The cross-pollination of Tosafistic and Kabbalistic modes of learning with Rabbenu Yonah’s Sefardi background apparently encouraged his spiritual creativity.

After returning from France, Rabbenu Yonah ultimately settled in nearby (but larger and shinier) Barcelona. There he established a yeshiva that soon drew many students. To Rabbenu Yonah’s students is attributed much of the work of recording his public addresses and lectures, including his commentary on the Talmud. More work from the school of Rabbenu Yonah is still emerging from manuscript. Like many of the Rishonim, Rabbenu Yonah planned to make aliyah towards the end of his life. However, as he made his way, stopping in Toledo, he was convinced by the community to stay on. Rabbenu Yona died there in 1263, just as things were heating up in Barcelona for his cousin and in-law, the Ramban.

Rabbenu Yonah’s Musar (Ethical Works)

Within Jewish tradition, there is a tendency to view musar, ethical works, on an age-old continuum. On this view, the works of Sefardi Rishonim in this area, including those of Bachye Ibn Pakuda and Rabbenu Yonah, are integrally connected to what came much later. Academic scholarship, in contrast, emphasizes the discontinuity between medieval ethical thought and the modern musar movement initiated by R. Yisrael Salanter and made famous at the Slobodka yeshiva.

I would suggest that both views are important and need not be contradictory. The musar of Rabbenu Yonah naturally responds to very different cultural conditions than does that of R. Salanter, and harmonizing them into a unified body of thought can make us miss their beautiful particularities. At the same time, it’s important that later musar thinkers saw themselves as working within an established tradition. There are intriguing commonalities, in particular concern with laxity in religious observance and an emphasis on self-reproach.

Rabbenu Yonah’s masterpiece of musar is Sefer ha-Teshuva (“The Book of Repentence”). Here is a small taste:

כדרך שיש לגוף חולי ומדוה כן יש לנפש. ומדוה הנפש וחוליה מדותיה הרעות וחטאיה. ובשוב רשע מדרכו הרעה ירפא הש"י חולי הנפש החוטאת. כמו שנאמר (תהילים מ״א:ה׳) ה' חנני רפאה נפשי כי חטאתי לך, ונאמר (ישעיהו ו׳:י׳) ושב ורפא לו.

In the same way as the body has sicknesses and ailments, so too does the soul. And the ailments of the soul and its diseases are its evil traits and its sins. But when an evildoer repents from his evil path, God, may He be blessed, heals the soul of the sinner - as it is stated (Psalms 41:5), “O Lord, have mercy on me, heal my soul, for I have sinned against You.” And it is [also] stated (Isaiah 6:10), “and repent and save itself.”

Rabbenu Yonah, Shaarei Teshuva 4 (English translation by R. Francis Nataf)

Also attributed to Rabbenu Yonah is Sefer Yirah (“The Book of Awe”). His commentarial work on Mishlei and Pirkei Avot also exhibit his interest in ethics.

Rabbenu Yonah in the Fray of the Maimonidean Controversies

Rabbenu Yonah was impelled to enter the contentious debate over Rambam’s Moreh ha-Nevuchim (Guide of the Perplexed) at the behest of his teacher R. Shlomo of Montpellier. Often portrayed as a reactionary, R. Shlomo was in actuality, like most Provençal Jews, a moderate who displays great respect for Rambam generally. In many ways R. Shlomo was caught in the winds of change, in which Greco-Islamic rationalist thought washed over Provence, translated for a hungry audience by émigrés from Sefarad. (The term Greco-Islamic refers to classical Greek thought translated and transmuted in Islamic culture, in particular the thought of Aristotle, whence it reached Rambam.) Rabbenu Yonah's role in the controversy is layered and fascinating and a little too big for this newsletter,2 but he was a worthy opponent for the Maimonidean loyalists. And he took a lot of flak: his reputation, along with that of his cousin the Ramban, was tarnished when he was accused of impure lineage. But, by the accounts we have, Rabbenu Yonah was chastened (like many in the anti-philosophy party) by the public burning of the Moreh.

His student, R. Hillel of Verona (who was Italian but only ancestrally from Verona), recalled vividly in a letter written c. 1290, some sixty years after the events in question, that Rabbenu Yonah repented of his actions in the controversy:

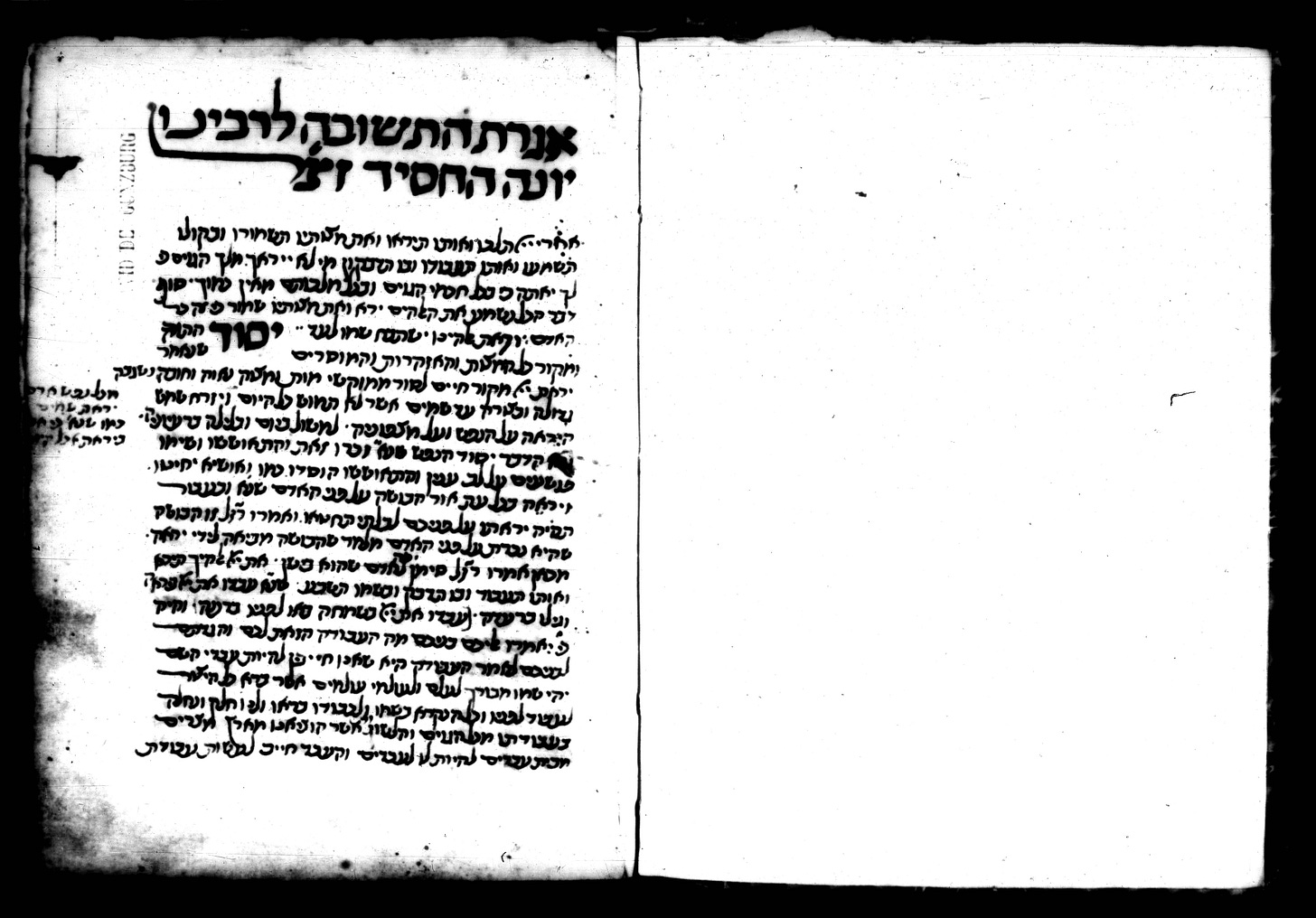

והר' יונה הגדול מברצלונה זצ"ל היה ראש וקצין על כל אותם הרעות הגדולות שנעשו בצרפת ואז נמס לבבו ולבב כל עוזריו וקבל עליו ללכת ולהשתטח על קבר רבינו…שימחול לו על אשר מעל בספרים והודה בפיו בפני כל העם ואמר בלשון זה: הנני מכה על פני ובוש ומתחרט על אשר פערתי פי נגד רבינו הקדוש הר' משה בן מיימון וספריו והנני מודה מלב ומנפש ואומר משה ותורתו אמת…כלשון הזה אמר בבית הכנסת של פריש לפני הקהל הנותרים מן הגזירה… בברצלונא ישבתי ג' שנים ושמשתי לפני מורי הר' יונה והוא הצדיק ספר לי מפיו אות באות כאשר כתבתי לעיל ככל אשר עשה וכל אשר קרהו עד יום צאתו מברצלונה ללכת אל טוליטולא ואני הייתי בברצלונא בנוסעו ונשקתי את ידו בעת הפרידה וברכני…

The great Rabbi Yonah of Barcelona, of blessed memory, was the leader and overseer of all those great wrongdoings that happened in France; but afterwards his heart softened like the hearts of all his followers and he took it upon himself to go and prostrate himself upon the grave of our Rabbi [Rambam]…so that he be forgiven in his inappropriate actions against his books, and he pledged to do so before the assembled people, saying in these words: “Here I am hitting myself in shame and regret for opening my mouth against our holy teacher, the Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, and his books, and here I am admitting from the depths of my heart and soul, stating that Moshe [Rambam] and his Torah are true…” In these words he spoke in the synagogue of Paris before the congregation that remained after the decree [against the Talmud]… I stayed in Barcelona for three years serving before my teacher, Rabbi Yonah, and he, the righteous one, himself told me, word by word, exactly as I have written above, just as he did and just as it happened until the day he left Barcelona to go to Toledo. I was in Barcelona when he departed and I kissed his hand at the time of our parting and he blessed me…

R. Hillel of Verona, Letter to R. Yitzchak the Physician (Published here)

As is evident from the letter, R. Hillel had become a staunch Maimonidean, and his account must be read from within that framing. At the same time, the preciousness of such an account is patent. This is but a small excerpt; the letter replete with details about the events surrounding the public burning of the Moreh and the Talmud (which R. Hillel seems to conflate)—it is, in fact, the major source of our knowledge.

For R. Hillel, Rabbenu Yonah’s repentant nature was born in the ashes of the burnt Talmud. Whether this was so may well remain in the heart of Rabbenu Yonah. For us, his exacting ethical stance and the stirring nature of his musar surely reveal a sensitive and turbulent soul.

Rabbenu Yonah Reads & A Listen

Sefaria, as usual, has a rich selection of texts by Rabbenu Yonah, including English translations of his musar works.

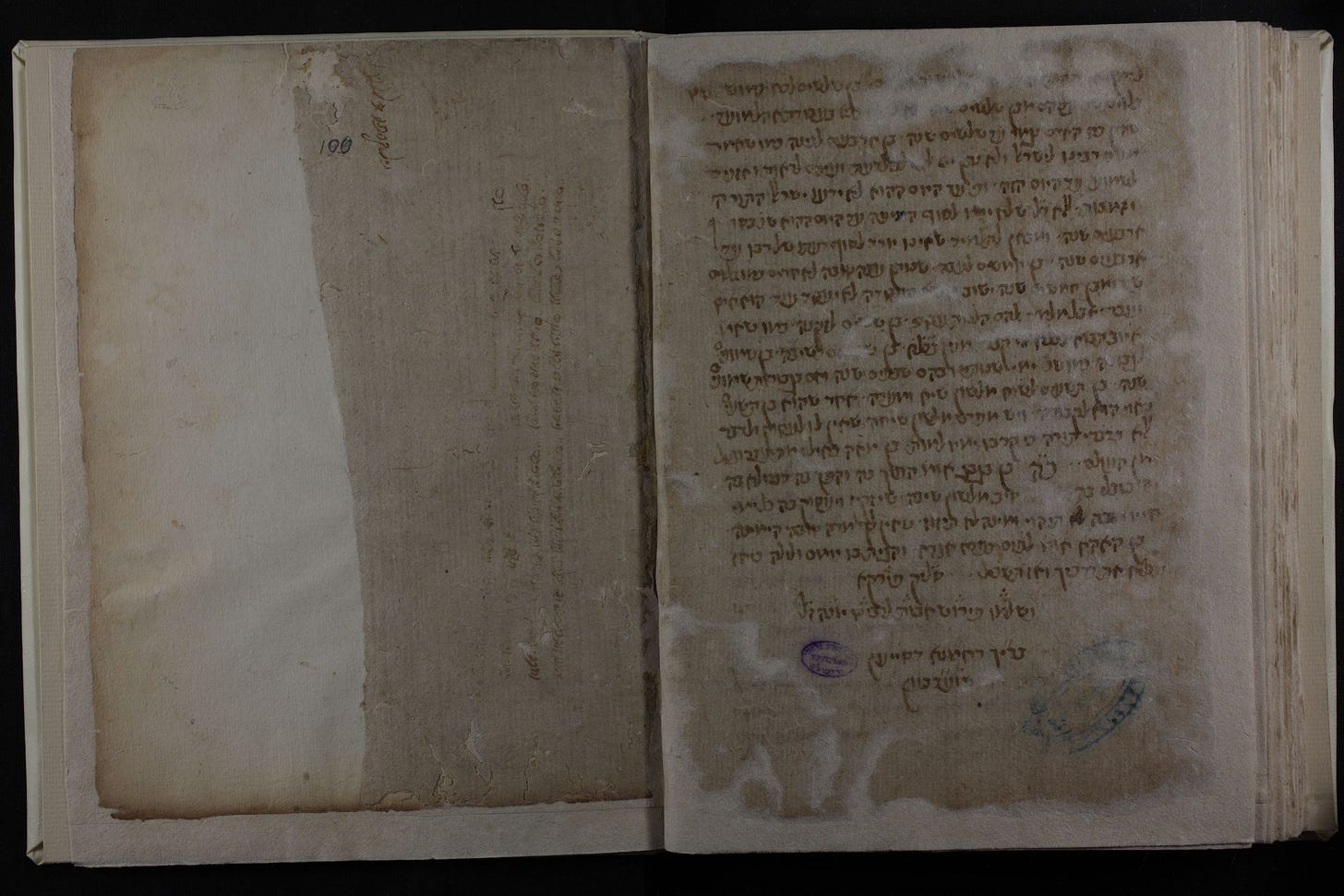

Ofeq Press, an imprint of Koren, puts out amazing critical editions of important texts from manuscripts; its Pesach Haggadah from the school of Rabbenu Yonah (written by his students) is available here.

And a listen: Great Seforim to Know About: Rabbeinu Yonah on Pirkei Avos by Rabbi Yehuda Turetsky on YUTorah.

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

Okay, this isn’t a Jewish resource per se, but I wrote up a guide to using Zotero. I suspect more than a few of you are confirmed bibliophiles, and there’s no better way to create your own personal digital library (or beit midrash!) than Zotero. It’s is a free reference manager initially created at a university (it’s now an independent nonprofit) and with a little technical setup, you can use it to catalog the riches of the interwebs, including saving and storing PDFs, making lists of articles you want to read, taking and filing notes on them, and pulling up anything you’ve saved at a moment’s notice.

Rabbenu Yonah on Twitter

Next Coffee Date

Are you ready for this? RAMBAN.

For an account of the historical evidence supporting the substance of Rabbenu Yonah’s remarks, see Yom Tov Assis, “Sexual Behaviour in Mediaeval Hispano-Jewish Society,” in Jewish History: Essays in Honour of Chimen Abramsky, ed. Ada Rapoport-Albert and Steven J. Zipperstein (London: P. Halban, 1988), 25–59.

Someone should write a book…okay, it’s me, I’m writing the book. I’ve got a number of things in the pipeline first, however.