Coffee with Maran Yosef Karo

☕ A staggering genius, R. Yosef Karo lived through the signal events inaugurating early modernity and single-handedly created the dividing line between the era of the Rishonim and of the Acharonim.

Hello! You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. It’s official: today we enter early modernity. Okay, not really; as we’ve been saying, it’s a fuzzy boundary. But in terms of internal Jewish chronology, we’re crossing over to the age of the Acharonim, “latter authorities,” where, arguably, we still find ourselves today. That’s right, it’s the Shulchan Aruch’s world; we’re just living in it.

In this issue:

From Iberian Exile to the Land of Israel

Known to Sefardim as Maran, to Ashkenazim as the Mechaber (“the editor” or “the compositor”), R. Yosef Karo was born on Iberian soil in 1488, probably in the heartland of Castile, Toledo.1 When the edict of expulsion of all Jews from the united kingdom of Aragon-Castile came down in 1492, the Karo family fled to Portugal. The personal, logistical, socioeconomic, and psychic impact of this order of expulsion cannot be overstated. It affected the largest community of Jews in Iberia, as well as in Europe at the time. As we’ve seen, Jewish life in Christian Iberia had been subject to pressures, often urgent and violent, since the Ramban’s day in the long thirteenth century. Nevertheless, even considering the mass violence and waves of conversions that swept through Iberia in 1391-92, the total elimination of Jews from Castile-Aragon, a community that dated to the Roman Empire, was a great shock.

Those Jews who chose not to convert to Christianity had to leave. Many, like R. Yosef Karo’s family, went to Portugal. Unfortunately, the power couple of Spain, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, pressured Portugal (along with the smaller remaining kingdoms) to expel their Jewish residents as well, not wishing them to reap the economic benefits of a Jewish community that Castile-Aragon no longer had. The king of Portugal, needing a political marriage hinged upon expelling Jews, reluctantly agreed. However, he engaged in some of the most aggressive and painful tactics to keep the Jews he didn’t really wish to expel in his kingdom. This included separating parents from children and baptizing them, as well as trapping Jews on boats set to leave the Lisbon harbor only to board them and forcibly convert all Jews on board. Maran’s family were among the “fortunate” ones: they managed to leave Portugal in 1497. Against such events did the young Yosef come of age.

Following, again, the route of so many Iberian exiles, the family found its way to the newly-minted and bustling Ottoman Empire, settling first at Constantinople (now, Istanbul, or, as Jews called it, Custa). When Yosef’s father, Ephraim, died at a young age, his uncle took over his education. By 1522 Maran sought his own fortune, moving to Adrianople (today’s Edirne), Nikopol, and then Salonika (something like, we might say, the Chicago, Miami, and Los Angeles of Turkey in those days).

Along the way, R. Karo met compatriots and brushed shoulders with the colorful messianic figure Shlomo Molcho. Molcho, born Diogo Pires in Portugal, was a Marrano—the pejorative descriptor of forcibly converted Portuguese Jews.2 He returned to Judaism, was circumcised by another messianic pretender, David Reuveni, studied Kabbalah, and eventually made overtures to the pope and Holy Roman Emperor. The latter did not take kindly to Molcho’s messianic pretensions and had him tried, whereupon he was burned at the stake as a Christian heretic in 1532. This public martyrdom impressed itself upon the Mechaber’s consciousness.

This turbulent, teeming, even ecstatic Ottoman landscape was his background. He lived in Turkey for approximately the first forty years of his life. But he was just getting started. Maran was to make his mark at the end of exile: in Eretz Yisrael, now under Ottoman rule.

One Code to Rule Them All

While still in Adrianople, at the age of thirty-four, Maran began work on his masterpiece, which would take him twenty years to complete. His goal was ambitious and born in worry: concern that the exigencies of the time—especially the traumatic dislocation of Iberian Jewry—were leading to a multiplicity of halachic rulings. This sense of unruly diversity was certainly informed by a key feature of early modernity, which, due to expulsions from Western Europe, brought together disparate Jewish communities. In the Ottoman Empire, for example, Iberian Jews met the older Romaniote community, which had been there since Byzantine times. Rather than assimilate into the local Jewish community, Iberian Jews (split into communities representing more specific locales of origin) remained distinct, while Romaniote Jews retained their separate shuls, customs, and traditions, even as they lived side by side with the emigres.

But the Mechaber was also responding to the totality of halachic thought developed so fruitfully throughout the period we now call that of the Rishonim. He rightfully sensed that this body of law needed consolidation—that the extant codes were confusing, at times conflicting, and lacked cohesion and comprehensiveness. Consulting, by his count, thirty-two separate works, R. Karo sought to trace each law from its sources through present-day discussion. Though he had been granted semicha by R. Yaakov Beirav, who, in light of renewed Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel, sought to reinstate authoritative ordination, the Mechaber did not rely on this authorization to issue rulings. Instead, he devised a majority-rule method in which he decided disagreements based on the triumvirate of the Rif, Rambam, and Rosh.

What he accomplished is simply staggering. The Beit Yosef presents a panoramic but analytical picture of the near-totality of discussion on each halachic topic relevant in his day. Importantly, he chose to format his work as a commentary on R. Yaakov ben Asher’s Arbaa Turim. The Tur, as we’ve noted earlier, was brilliant in its pragmatic organizational scheme, which for all intents and purposes R. Karo codified as the taxonomy of halachic subjects.

In the meantime, far off in snowy Kraków, a strikingly similar project was undertaken by the great Ashkenazi posek Rema, R. Moshe Isserles. When the Beit Yosef was first published in 1555 and Rema caught wind of it, he set aside his task. Crucially, however, Rema didn’t quit. Instead, he reformatted his work as a commentary on the Beit Yosef, titled Darchei Moshe. This brought Ashkenazi halachic traditions in to inform the Mechaber’s Sefardi focus, which was to be decisive in the eventual acceptance of his method.

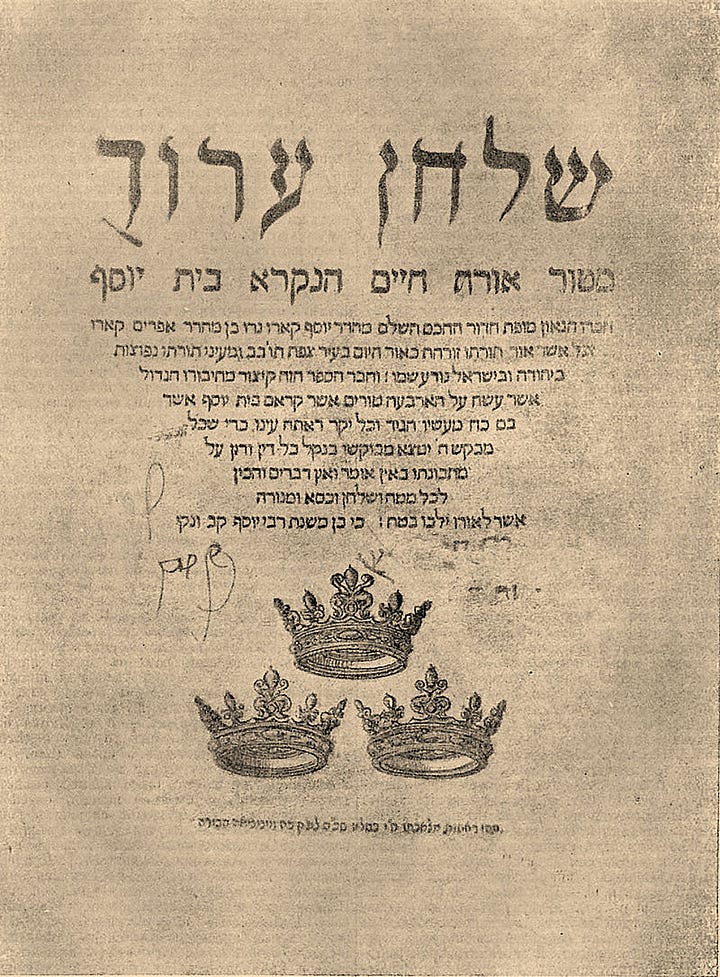

Later, Maran was compelled by what he saw as a great need to compile a bottom-line summary of the conclusions of the Beit Yosef. This work became the celebrated Shulchan Aruch, first published in Venice in 1564-65. Here too, Rema added Ashkenazi thought via glosses (haggahot) on the text, first printed in the Kraków edition of 1569-71. Because of this comprehensive nature, the concise code became acceptable to nearly the entire Jewish world.3 Thereafter, commentary centered around the Mechaber's work, ushering in the era of the Acharonim.

Among the Kabbalists of Tzfat

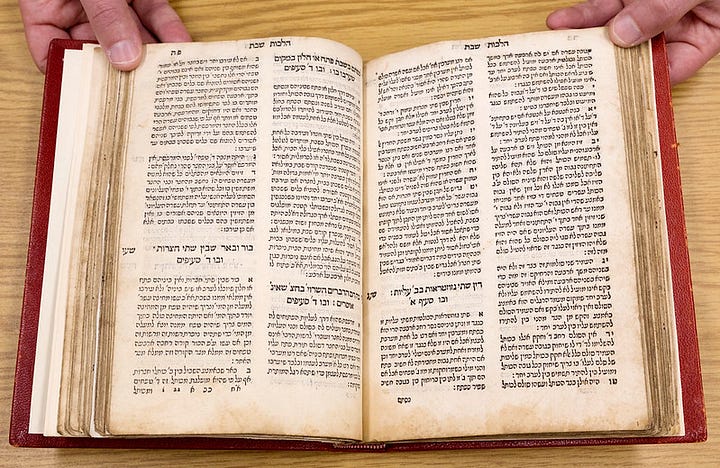

Although it finds scant expression in his halachic magnum opus, the Mechaber was deeply involved as a Kabbalist. From his time in Adrianople, Nikopolis, and Salonika, he was involved with circles of initiates seeking both theosophical knowledge and ascetic-mystical experiences. For fifty years, R. Karo was visited by a heavenly figure he called a maggid (“sayer”) who spoke to him and occasionally approved his rulings, particularly when they came from Kabbalistic sources such as the Zohar, the great mystical midrash that surfaced in Castile in the late 1200s. It also sometimes spoke through the Mechaber, such that others could audibly apprehend what the maggid was saying. At times, others witnessed this and recorded it. R. Karo himself recorded many visitations of the maggid in a diary called Maggid Meisharim, one early manuscript of which is pictured above. In its published form, it was reorganized as a commentary on the Torah.

In Tzfat, the Mechaber was involved in the Kabbalistic fellowships for which the city became known in the sixteenth century. The renowned Kabbalist R. Moshe Cordovero, a teacher of the Arizal (R. Yitzchak Luria, the initiator of a new, highly generative school of Kabbalah), referred to the Mechaber as his master. R. Shlomo Alkabetz, with whom R. Karo had been close already in Turkey, also turned up in Tzfat. R. Karo’s circle represents the apex of pre-Lurianic Kabbalah, and despite being eclipsed by the Ari’s school, its ideas nourished later Kabbalah.

Maran was what I call a “dayenu” scholar: if he had only written Kesef Mishneh, it would have been enough; if he had only written the Beit Yosef on Orach Chaim, it would have been enough; if he had only contributed to Tzfat mystical circles, it would have been enough… But he produced all of these epoch-making works and ideas, and the Jewish world is unrecognizable without them.

Mechaber Reads

Al-HaTorah has an amazing edition of Shulchan Aruch and Beit Yosef. The latter is available on the Tur (here, in dual view; you can also view it in different layouts) or as Tur-Shulchan Aruch including the Beit Yosef. Their edition of Kesef Mishneh (you might have to toggle it on under the Mishneh Torah text in the link) is also excellent; this is R. Karo’s definitive commentary on Mishneh Torah, which I didn’t even have the space to mention above). These works, along with Maggid Meisharim, are also available on Sefaria. There are countless print editions, including many beautiful ones, of these works. My favorite Tur-Shulchan Aruch is Machon Yerushalayim’s Friedman edition.

I was brought up and remain a major R. Dr. Isadore Twersky fan. Though there’s a lot of newer research, I think his essay on the significance of the Shulchan Aruch is an unsurpassed classic (the link will go to a PDF; it’s not such an easy article to find).

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

Last but absolutely not least, an invitation to explore, if you’re not already familiar with it, Ktiv, the amazing website of the Institute of Microfilmed Hebrew Manuscripts at the National Library of Israel. The purpose of this vast digital collection is to organize in one place all the various Jewish manuscripts scattered in libraries worldwide. It’s an indispensable research tool that I use near-daily. It’s also where I find almost all of the manuscript images you see in this newsletter and my website (images have information about permission to reproduce in the manuscript viewer). Even if you’re new to using manuscripts, Ktiv is fun and fruitful to explore. (My guide to accessing Hebrew manuscripts is here.)

R. Yosef Karo Twitter Thread

Still not properly embedding, ugh.

https://twitter.com/tamar_marvin/status/1652898906898931712?s=20

Next Up

That’s a wrap! (As they say here in Lalaland.) Series One of Great Rishonim is tam ve-nishlam. Look out for two recap newsletters to highlight what we’ve covered. After that, we dive into a series on famous Hebrew manuscripts.

There are some scholars who suggest that he was born in Portugal, after the family had fled Castile.

Portuguese Marranos differ from Conversos from other parts of Iberia in that most were converted under extreme duress, whereas elsewhere, though certainly duress was a significant factor, we also see mass conversions out of ecstasy and expediency. Due to this differential, the term Marrano is still used by historians.

An important exception is the Yemenite Jewish community, which continued to rely upon the Mishneh Torah.

Another great article! And YAY for your inclusion of AlHaTorah links! :D

If I may make a non-substantive niche-meme comment, in response to your "One Code to Rule them All": it may be said that R' Moshe Isserles's original project (before he changed his plans) reflected his ambition of "Ashkenaz durbatulûk, ashkenaz gimbatul, ashkenaz thrakatulûk, agh burzum-ishi krimpatul."

I've enjoyed all your Stories from Jewish History, but this one is the tops.

Really makes the era and the man come alive.

Thank you for making your scholarship accessible to the layman.

Looking forward to more.

Best,

Steven Drucker

Dust and Stars