Coffee with Ramban

☕ Ramban might have lived the quiet life of a Kabbalist in Girona. Instead, he changed Jewish history with his integratory methods, abundant insight, personal leadership & groundbreaking scholarship.

Hello! This Tuesday in Stories from Jewish History we’re at ground zero of a fertile new era of Sefardi-Ashkenazi integration, one that would shape the beit midrash for centuries to come. At the healm? The great Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman (Ramban), whose fame was such that he was known as just “the rabbi” or ha-rav ha-neeman, “the faithful rabbi,” among Spanish Jews and later among Christians by the classicized name Nahmanides (the Greek suffix -ides meaning “son of”).

In this issue:

Ha-Rav ha-Neeman: The Faithful Rabbi

With the establishment of Ramban’s yeshiva, a major school of Sefardi Torah learning was born. It would stretch on, growing and developing on the firm foundation of the Ramban’s synthesis, over the long thirteenth century and beyond. Following the “foundational” Rishonim—especially Rif and Rashi—the output of Ramban’s beit midrash has formed an important, substantive core of the study of halacha until today. It is difficult to study any halachic topic without bumping into Ramban, Ran, and Rashba. Ramban’s school would come to represent the integrated apotheosis of medieval Sefardi tradition.

Ramban was born c. 1194 in Girona, a smaller city up the coast from Barcelona. There he lived most of his life, though he spent time in Provence pursuing his studies and in Barcelona when summoned there by King James I (“the Conqueror”) of Aragon. Barcelona, in the lifetime of the Ramban, had become the glittering capital of Aragon with a rich Jewish cultural life, while Girona was known for its mystics, including among them Ramban. The archives of Catalunya hold a fairly robust amount of material about Bonastrug da Porta, as Ramban was known in the vernacular, a sought-out physician with ties to the ruling class.

Descended from a colleague of the Rif’s on his father’s side and from an established Gironese family on his mother’s,1 Ramban was ensconced in both older Andalusi trends in Sefardi thought and newer currents brought in by northern Spain’s unification with Christian Europe following a century of Christian conquests in the Iberian peninsula. This is reflected in his work, which displays the Rif’s characteristically Sefardi interest in resolving halachic questions while also adopting the methods of his primary teachers, both Tosafists, including R. Meir of Trinquetaille, a Provençal.

On the Deep Jewishness of Ramban’s Thought

In Ramban’s thought coalesce an array of themes, genres, and methods. It is as if he, like a prism, absorbs the light of his time and refracts it back—in technicolor. He wrote in basically every major Jewish form, penning an extensive Torah commentary,2 chiddushim (“new interpretations”) on the most commonly-studied tractates of the Talmud, works devoted to specific halachic topics, theological essays, responsa, sermons, piyutim (liturgical poetry), and hassagot, critical glosses (in-line notes) in defense of the Rif and the Geonic tradition.

Standing on the shoulders of his illustrious predecessors, Ramban managed to look ever farther. His Torah commentary, for example, is far lengthier and more thematic than any that came before him. It takes into account and discusses earlier commentaries, including Rambam’s takes, even though Rambam did not write a direct Torah commentary. (Instead, Rambam inserted his observations elsewhere, especially in Moreh ha-Nevuchim (The Guide of the Perplexed).) It has been suggested that Ramban is the first of the Mefarshim (commentators) to really lean into the concept of pardes interpretation, an acronym that reflects the four coexistent levels of meanings latent in the holy text. For Ramban, the level of sod contained esoteric secrets to which he briefly alluded, opening Kabbalah just slightly before his reader. In many places, Ramban’s Torah commentary is a series of mini-essays, and he includes comments on his theology and exegetical methodology throughout the commentary.

In a work like Torat ha-Adam, I think we see a deeply Jewish philosophy, by which I mean its subjects and methods are internal to traditional modes of Jewish thought. Rambam, the medieval philosopher par excellence, consciously sought to apply the powerful categories and methods of Aristotelian rationalism to the revealed truths of Torah. This use of “external” knowledge engendered fierce public controversy for that (among other) reasons—controversy into which Ramban was unwillingly dragged and on which he exerted a moderating force. Compare this to Ramban’s book about death and mourning, ostensibly and indeed primarily a halachic book. That is, it approaches this sensitive and human area from within the perspective of rabbinic concerns. At the same time, Torat ha-Adam’s final section deals with eschatology, the study of what happens at the end of time and after death. The format, treatment, and subject matter are traditional, but their union in this one book bears the unique stamp of the Ramban, as do the careful and fascinating ideas that he offers.

The Disputation of Barcelona and its Aftermath

The thirteenth century marks a significant turning point for Jewish life in medieval Christian Europe. Earlier church doctrine had advocated the preservation of Jews as “witnesses” to the future redemption that would prove Christianity’s truthfulness. Though discriminatory by design and often tolerant of grave violence, this doctrine created a space for Jews to live as a semi-autonomous community in Christian societies. Following the consolidation of papal power and the rise of the mendicant orders of monks, a palpable shift occurred in Christian relations to the tiny Jewish minority in its midst. Instead of tolerating Jews, the Franciscans and Dominicans sought to convert them, creating a unitary Christendom. Aided by Jewish converts to Christianity, the friars began to realize that Jews were not following the Bible, but the Talmud. They sought to use the Talmud and Midrash to persuade Jews of the truth of Christian doctrine.

These trends had already found violent expression in the earlier decades of the thirteenth century, but they came to a head in Barcelona in 1263, when a debate was staged by one Pablo Christiani, a former Jew turned zealous friar (this assumed name is very much like “Joe Christian” in Catalan). Pablo wanted to debate the greatest rabbi in the land, and that rabbi was, you guessed it, Ramban. Despite his ties to the monarchy, though with assurances of protection from James I, Ramban was compelled to appear at the disputation, which took place in July of 1263, when Ramban was already elderly. We possess both a brief Latin account (which, naturally, portrays Pablo as the victor) and Ramban’s own lengthy Hebrew account, rich in detail. It seems clear that Ramban’s performance was strong enough to attract the continued harassment of the friars. In light of impending arrest, Ramban decided to get out of dodge.

But, as we’ve seen time and again, that was not nearly the end. Ramban left Spain and made aliyah, where he lived for a time in Jerusalem (he describes the community, sadly, in a state of disrepair) and served as rabbi in the community of Akko (Acre). In Eretz Yisrael, he corrected his Torah commentary based on the realia he encountered there, such as ancient coinage he was privy to. I treasure the thought of an aged Ramban walking the quiet streets of Yerushalayim or taking in the Akko sunset. In this last trajectory, too, he has much to teach us.

Ramban Reads

For a nicely-formatted edition of Ramban’s thought essays, see the edition of R. Chaim Chavel, which has been translated into English as well.

There is a graphic novel about the Disputation of Barcelona called Debating the Truth (written by a scholar!).

There is of course a huge literature on Ramban, but I recommend this exciting and accessible articles by R. Dr. Yaakov Elman, “‘It Is No Empty Thing’: Nahmanides and the Search for Omnisignificance,” Torah U-Madda Journal 4 (1993).

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

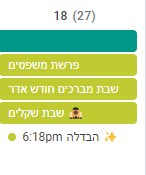

I’m a huge fan HebCal.com (though I do wish they had an all-Hebrew interface). For figuring out upcoming holidays, Torah readings, converting dates, downloading a customizable calendar (there’s a tool for yahrzeits too)—for everyday calendar question—it’s unbeatable. (It doesn’t quite work for complicated stuff like pre-Greogrian historical dates, etc.) Here’s how the custom gCal looks outputted in my calendar (for upcoming February 18/27 Shevat):

Ramban on Twitter

Next Coffee Date

Next week we’re hanging out with the Ran!

Ramban’s cousin was Rabbenu Yonah Gerondi.

Ramban also wrote a Commentary on Iyov (Job) and interpreted much of Daniel in Sefer ha-Geulah.

I quite enjoyed Coffee with Ramban and recommended Stories from Jewish History to my readers. Apropos your endorsement of HebCal, can I recommend Dust and Stars--Today in Jewish History to complement it? Subscribers receive a free post every day highlighting events in our most unlikely story and the remarkable Jews who have literally touched billions of lives.