Coffee with Terumat ha-Deshen

☕ Before Coffee with the Achronim kicks off, a virtual cup with a transitional figure that some call the first Acharon: Yisrael Isserlein, the pious Trumat ha-Deshen.

In this issue:

This newsletter kicked off with a series called Coffee with the Rishonim, which featured introductions to major figures of the medieval period. I always meant to return to do a second series, because choosing which Rishonim to include is a lot like picking my favorite child. (They are all my favorite, of course.) When I recently went to draw up a second Rishonim series list, however, I realized that I’d covered a lot of the “missing” Rishonim over time in different series, such as Origins of Sefarad, which included a number of Andalusi poets and thinkers like the Ri Migash and Yehuda ha-Levi. As we’re nearing 100 issues (!), I thought it was time to make an introductory post and index that arranges all the posts from all the series topically and chronologically. You can browse that here.

That’s not to say that I’ve covered every major Rishon, let alone all the fascinating Jewish figures of the Middle Ages. We haven’t yet talked about the prickly related duo of R. Zerachia ha-Levi (Razah) and R. Aharon ha-Levi (Ra’ah), or the steadfast Mordechai, or the staunch R. Avraham Maimuni, and many others. I hope בע”ה to write about them all in the future, one way or another. But I couldn’t help but come to the conclusion that it was time—for Coffee with the Achronim!

“Rishonim” and “Achronim” are slippery terms. Already in the Talmud, there are authorities referred to as Rishonim—earlier scholars—and Achronim—later scholars. (I have written a lot more about these terms and how they are used in context of the concept of yeridat ha-dorot, the decline of generations, in The Lehrhaus.) As I wrote about in the newsletter about R. Yosef Karo, the Mechaber (compiler) of Shulchan Aruch, there are various ways of drawing the line in our present-day schema between Rishonim (roughly, medieval authorities) and Achronim (early modern to modern rabbinic authorities). I like using the Shulchan Aruch as a dividing line—specifically, 1570, they year it was printed along with the Rema’s glosses,1 allowing its adoption by Ashkenazi and Sefardi Jews alike. More precisely, according to this view, it is the orientation of later authorities towards the Shulchan Aruch as the authoritative code of Jewish law that makes them Achronim.

Nevertheless, other compelling schemas exist. One of them draws the line right through the Iberian expulsions, beginning with the great expulsion from Castile-Aragon in 1492. Another places those figures operating in a humanist, Renaissance framework on the side of modernity. And some even suggest that the subject of today’s newsletter, R. Yisrael Isserlein, better known by the title of his magum opus, the Terumat ha-Deshen, is the first Acharon, consolidating as he did Ashkenazi halacha. I would submit that the Terumat ha-Deshen is a transitional figure, one that anticipates, in his consolidation of Ashkenazi custom, the transformations that would change the medieval mentalité into something we can recognize as a modern one.

R. Yisrael Isserlein: Early Life and the Vienna Persecutions

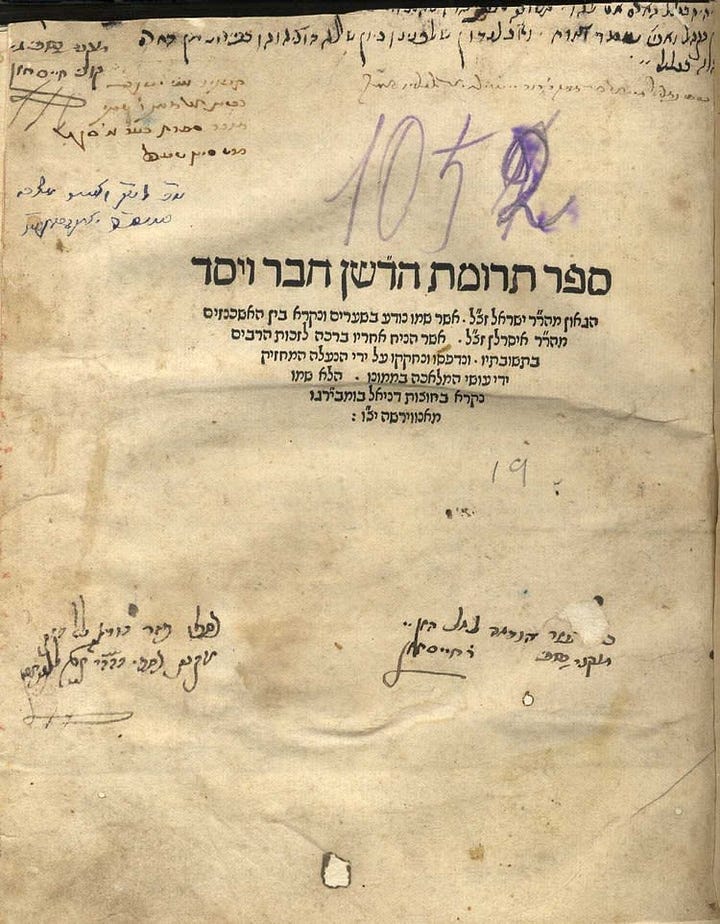

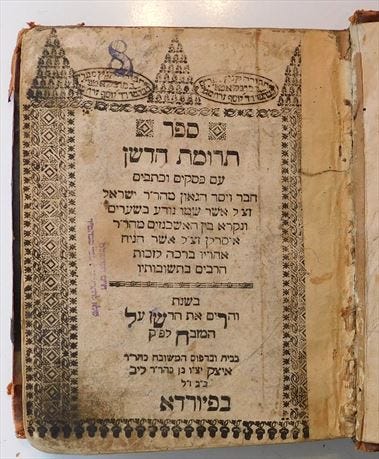

R. Yisrael ben Petachia (1390-1460) is known today by the surname Isserlein, the name of one of the German towns in which he served as rabbi—others were Marburg and Neustadt, names by which he was also sometimes called. Then and now, however, he is usually referred to as the Terumat ha-Deshen after the title of his most celebrated work. Essentially a work of responsa, the book is composed of 354 rabbinic replies, which leant the book its name, deshen having the value of 354 in Hebrew numerals. (The phrase terumat ha-deshen refers to the ritual act of clearing the ashes left over from the overnight burning of offerings on the altar of the Beit ha-Mikdash, described in Vayikra 6:3.) R. Isserlein’s Terumat ha-Deshen is more than a standard work of responsa, in that it is one of the main vectors preserving Ashkenazi halakhic traditions and customs.

Though born at Regensburg in southern Germany, R. Yisrael was known as Austrian, as his family was based there, and it was there he spent most of his early years. His great-grandfather, R. Yisrael (of) Krems, a city in Austria, is better known as the Asheri, based on the name of his commentary on the Rosh (R. Asher ben Yaakov), the Haggahot Asheri. Though initially taught by his father, young Isserlein was ultimately a student of his mother's brother Aharon Plumel (or Blumlein) in Wiener-Neustadt after his father’s early death. (Not to be confused with Wien/Vienna, Wiener-Neustadt is a smaller city south of the Austrian capital.)

Then, in 1420, when Isserlein was about thirty, brutal prosecution of Jews began in Austria, which built up to the Wiener Gesera (Vienna Persecutions) that broke out in the city and its environs in 1421. These persecutions were fueled by a number of factors. The first was a host desecration libel promulgated around Easter 1420, in which the accused Jews were brought to Vienna, imprisoned, and tortured. By May 1420, Jews across Austria had their belongings seized, with the wealthy being imprisoned and the rest forcibly set to sail on the Danube. There was widespread separation of families, including children from the parents, and forcible conversions of the imprisoned and terrorized Jews to Christianity. These intense persecutions took place against a backdrop of increasing anti-Jewish animus stoked by burgher resentment of Jewish wealth, as well as the Hussite rebellion. The Hussites were a breakaway group of Christian reformers, considered heretics by mainline churches; the Jews were considered to be Hussite allies. Duke Albrecht V of Austria (later Albrecht, or Albert, II of the Holy Roman Empire) was not only a religious extremist disturbed by the Hussite heresy, but also deeply in debt to Jewish moneylenders. This was a perfect storm.

The leadership of the Jewish community in Italy attempted to intervene on behalf of the Jews of Austria to Pope Martin V, largely unsuccessfully. Though the pope issued a pro forma ban of excommunication on those who would forcibly convert Jews, this was largely ignored, with many of the separated Jewish children forcibly baptized. There were, as during the Crusader violence, incidences of suicide, and many of Austria’s surviving Jews were burned at the stake in March of 1421. These events effectively ended Jewish life in Austria for a time, with vanishingly few Jews remaining in the territory, some escaping to neighboring Bohemia. Vienna became known as Ir ha-Damim, the City of Blood (after Yechezkel 22:2). Both Isserlein’s uncle and mother were murdered in the Vienna Persecutions, and he escaped for a time to Italy. It was over two decades later before he returned to Wiener-Neustadt in 1445, where he was in short order appointed av beit din (head of the rabbinical court). More than serving in that capacity, Isserlein helped to revitalize the community, building a school around him and attracting students.

The Terumat ha-Deshen as Pietist, Teacher, and Scholar

Though the Chasidei Ashkenaz petered out as a movement in the thirteenth century, their distinctive asceticism continued to influence Ashkenazi culture, as it did the life and thought of R. Isserlein. R. Isserlein’s work shows the imprint of Sefer Chasidim, the unique customary preserving the traditions, behaviors, and ethic of the movement, and his own piety and asceticism were probably inspired by it.

We know an unusually copious amount of information about the pious practices of the Terumat ha-Deshen due to his student, R. Yoslein Österreicher, the author of Leket Yosher. Leket Yosher is both a halachic compendium and a record of R. Yoslein’s esteemed teacher’s life and pious customs.2 R. Yoslein, who also studied under the renowned R. Yaakov Weil, R. Yehuda ha-Levi Mintz, and Maharik (R. Yosef Colon) but considered R. Isserlein his primary teacher, poignantly writes about how he came to record R. Isserlein’s rulings and practices in the book’s opening:

ואני לא הגעתי עדיין לקראות אותי לא רב ולא חבר וכבר הגעתי למ' שנה ויותר ש"ל, אלא כך היה המעשה. בתחלה הייתי באושטריך אצל הגאון ז"ל כנגד ה' שנים, שלא כתבתי מספר הזה שום דבר. ואח"כ נתגלגל הדבר שהלכתי לארץ רינוס, ושאלו לי רבני הדור ידעת איך שנוהג הגאון ז"ל בזה הענין? ולא ידעתי להשיב להם דבר ודאי, ומקצתם לא היו ידוע [ידועים] לי לגמרי. וכשחזרתי אצל הגאון ז"ל שאלתי אותו אותן הדברים, והיה הדבר פשוט בעיניו. ואמר זה כתוב בתוס' זה כתוב בפוסקים…[ואמרתי בלבי] אכתוב לעצמי מה שאשמע ומה שאראה מן הגאון ז"ל, כדי שאדע להשיב דבר ודאי בשם הגאון ז"ל. כי הוא היה בסוף ימיו שאין בדורו במותו, כידוע לי. וגם חברי הפצירוני לכתוב בספר מה שאשמע מן הגאון ז"ל. והשבתי להם שאיני אוכל לכתוב בלשון צח, והם אמרו לי אם אינך תוכל לכתוב בלשה"ק כתוב בל"א, אי אפשר שלא נראה בו דבר אחד או שנים.

I have not yet attained the right to be called rabbi nor a chaver, although I have reached forty years of age and more, praise be to G-d, but rather this is how it came about. At the beginning, I was in Austria with the gaon [R. Isserlein] of blessed memory for some five years, during which I wrote nothing that appears in this book. Afterwards things took a turn and I went to the land of the Rhine, where the rabbis of my generations began to ask me if I knew how the gaon of blessed memory behaved in such and such a matter? I wasn’t able to answer them anything definitively, as some of them were not known to me completely. Thus when I returned to the gaon of blessed memory I asked him about those same matters, and the question was simple for him: he would say, “That is written there in the Tosafot,” or “That is written in the poskim.” …I said to myself, I’ll write down for my reference what I hear and what I see from the gaon of blessed memory, so that I will be able to respond [to queries] in a definite way in the name of the gaon of blessed memory. For he was at the end of his days and there is no one in his generation to succeed him, as I well know. In addition, my friends implored me to write down in a book what I heard from the gaon. I explained to them that I was not capable of writing in elevated language, but they told me that if I can’t write in Hebrew, I should write in vernacular, because it is not possible that we shall not see in it a thing or two [of value].

R. Yoslein, indeed, preserves the minutiae of R. Isserlein’s life, rich with prosaic details—like his morning routine—as well as substantive rulings and pious behavior. The picture emerges of an austere, serious, and compunctious individual.

Nonetheless, this did not render the Terumat ha-Deshen a necessarily strict decisor: though stringent in de-Orayta matters (those that are forbidden from the Torah), he otherwise shows a propensity to be lenient in his rulings. One of the hallmarks of Terumat ha-Deshen is R. Isserlein’s method, following waning Ashkenazi tendency, of eschewing more recent rulings in order to return to the Talmud text. In addition, he generally favors Ashkenazi halachic traditions, though he does cite the Rif, Rambam, Tur, and other Sefardi authorities. In general, he prefers the position of the Geonim over more recent opinions. For example, in one responsum (1:46) about reinforcing the hole through which tzitzit are threaded, R. Isserlein begins by citing Rashi and Rav Amram Gaon (d. c. 875) and analyzing their positions, ruling on this basis.

The Learned Women of the Isserlein Family

The Isserlein family was not only rabbinically prominent, but also part of the wealthy merchant class of Austrian Jewry. As such, R. Yisrael’s mother, wife, and daughters-in-law were well-educated, religiously active women who also participated in the family’s business ventures. (His only daughter, sadly, died in childhood.) R. Yisrael ruled that the morning blessing said by women should follow his mother’s version (see Leket Yosher 1:7). His wife, whose name we know to be Schoendlein, would personally check her private quarters for chametz (leavening) before Passover, which Isserlein believed to be an authoritative check (see Leket Yosher 1:81.) R. Yisrael and Schoendlin had four sons: Petachia, named for R. Yisrael’s father but known as Kechel, Avraham, Shalom, and Aharon. Of Kechel’s wife, Redel, R. Yoslein writes that following extraordinary account of her learning:

וזכורני שכלתו רעדיל ז"ל, לומדה לפני זקן אחד ששמו ר' יודיל סופר ז"ל בבית הגאון זצ"ל, במקום שרוב בני הבית הולכים שם ואותו זקן הוה נשוי.

I recall that his [Kechel’s] wife of blessed memory was taught by an elder named Rabbi Yudel Sofer of blessed memory in the house of the gaon [Isserlein], the righteous of blessed memory, which most of the household traversed, and that same elder was married.

Here we see not only that Redel, a fifteenth-century Jewish woman, pursued learning, but that she studied with a learned male in the house of her esteemed father-in-law. Her pursuit of knowledge was not obstructed by the concern of yichud (seclusion with a member of the opposite sex) because the studies took place in an open space of the home.

In addition to this, there are documents and other sources attesting to the business acumen of the Isserlein women, as well as a tender recollection in Leket Yosher of R. Yisrael blessing his daughters-in-law each Shabbat. This pious, serious leader valued Jewish learning and spiritual vigor among his sons and daughters alike.

Reads and Resources

You can read Terumat ha-Deshen on Sefaria or on Al haTorah (Hebrew only).

You can read Leket Yosher on Sefaria (Hebrew only).

On the “weirdness” of Terumat ha-Deshen as responsa, see Tirza Kelman, “What Makes a Text Responsa? R. Israel Isserlein’s Trumat Hadeshen as a Case Study,” Jewish Law Association Studies 30 (2022): 99–110.

The 1569/70 Krakow printing was of Orach Chaim, the first section (of four parts) of Shulchan Aruch with the glosses of Rema. The remaining three volumes were printed between 1578-1580. However, culturally speaking, I also like the year 1573 as a dividing line: the year of the Arizal’s untimely death in Tzfat (Safed). Perhaps 1580 covers all bases?

It is also worthy of note that Leket Yosher is one of the earliest works to adopt the structure of Arbaa Turim.