Coffee with the Or Zarua

☕The man behind the tome was born in the hinterland but came to be the student of an eclectic array of rabbis who spanned the medieval Ashkenazi world—becoming a foremost scholar himself.

Hello, friends, happy medieval Tuesday! If you’re drowning in emails, texts, and other 21st-century mixed blessings, may I suggest a hot beverage and a quick foray a 800-ish years into the Jewish past, where the phones don’t buzz (or, you know, even exist)?

Having put in quality time with Rashi and his illustrious descendants, we’re moving this week into the wider Ashkenazi world, teeming as it is with Torah, hardship, and unruly texts. We’re kicking off in Bohemia, but we’re not staying put long, because our subject today went to allll the places.

The Or Zarua (“Seeded Light”) is a name familiar to students of halacha (Jewish law), who come across his rulings regularly enough to belie the absolute tendentiousness of their survival. We know him because he is a vital early source of Ashkenazi halacha, a voice that survives the sixteenth-century codification of Jewish law. Meaning, despite standardization, his éclat lends such authority to a given halacha that it is cited in his name. Who ruled like this? Yitzchak Or Zarua did.

Once Upon a Time in Bohemia

R. Yitzchak ben Moshe of Vienna, better known as Yitzchak Or Zarua after the title of his massive halachic work, was born c. 1180, right around the time of Ri’s death. He was born not in the Rhineland, nor in France, but in Bohemia. I know what you’re thinking right now:

And here’s the thing, you’re actually not wrong: Queen was riffing off Puccini’s La Bohème, which popularized the notion of the “Bohemian lifestyle,”1 which was pejoratively and/or Romantically attributed to the Romani people—once known as “Bohemians” in French due to confusion about their origins, which placed them (incorrectly) in Czech Bohemia. So we can be somech (rely) on Freddie Mercury and Lorne Michaels to point us to where we need to be. Excellent.

So yeah, Bohemia was for most of European history a major province of Central Europe, kind of like a Virginia. Only pretend that instead of being eventually split into Virginia and West Virginia, whose names sensibly point to their former unity, the two parts of this venerable region were belatedly called the Czech Republic and Austria. BAM. You’ve got Bohemia.

To its Jewish denizens, Bohemia was known by the unflattering moniker “the land of Canaan,” and so the Or Zarua terms his Slavic glosses lashon Canaan, “the Canaanite language.” Bohemia was indeed something of a hinterland in the twelfth century, with its best and brightest finding their way to Regensburg and Prague. It seems that R. Yitzchak suffered from economic straits and possibly other misfortunates in his younger years; in any case, he was impelled to travel widely, his peregrinations taking him to a wide swathe of the medieval Ashkenazi world.

And it’s this that makes R. Yitzchak such an important tradent of Ashkenazi traditions. (Tradent is a cool word that I overuse because it’s just that good. It means “One who is responsible for preserving and handing on the oral tradition.”) Yitzchak Or Zarua went everywhere, talked to everyone, and wrote it all down.

There and Back Again

R. Yitzchak sought his first teachers in, yep, Prague and Regensburg, first studying under R. Yitzchak ben Yaakov ha-Lavan.2 Even coming from Prague, R. Yitzchak ha-Lavan had had to seek for himself teachers farther afield in Germany and France, chief among them Rabbenu Tam. This made the Or Zarua’s first teacher the premiere Tosafist of Bohemia.

His second teacher was R. Avraham ben Azriel of Bohemia, the author of Arugat ha-Bosem, an omnibus piyyut (but oh-so-much more) commentary. (I did a Twitter thread about the Arugat ha-Bosem here.) R. Avraham had learned with the Hasidei Ashkenaz, the great German pietist-mystics of the Rhineland, infusing his student with those traditions as well. The Or Zarua was already privy to the major trends of twelfth-century Ashkenazi thought, but he was just getting started.

From Prague R. Yitzchak went to Regensburg, and from there to Speyer, possibly Cologne (Köln), and Würzburg, followed by Paris and Coucy in France, acquiring teachers in each locale. The three whom he regarded as his primary rabbis were R. Simcha of Speyer, the Raavyah (of Bonn, but of many other places as well), and Yehuda Sir Leon of Paris. All were outstanding Tosafists of the generation following Ri (Yehudah Sir Leon being a direct student of Ri’s). This unusually large and broad set of mentors gave the Or Zarua grounding in the full array of Ashkenazi learning. From the margins he burst onto the very center of cultural life.

The Seeded Light

The fruit of these many wanderings and years of learning coalesced in R. Yitzchak’s magnum opus, the Or Zarua. It wasn’t just a belletristic (and comforting) name; R. Yitzchak had in him the touch of a poet. In his opening disquisition on the meaning and significance of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, R. Yitzchak writes:

ד"א אלף אפתח לשון פה אמר הקב"ה אפתח פה של כל בשר ודם כדי שיהיו מקלסין לפני בכל יום וממליכין אותי בארבע רוחות העולם שאילמלא שירה וזמרה שמזמרין לפני כל היום לא בראתי את עולמי.

The letter aleph stands for “I will open the tongue (also: language) of the mouth,” for the Holy One, blessed be He, said, “I will open the mouth of every living being so that they will exalt Me each day and declare My sovereignty over the four corners of the world, for were it not for the poetry and song that they intone before Me today I would not have created My universe.”

Or Zarua is today generally divided into four parts; it is a multifarious work, including the introductory section on the alphabet, followed by a section that encompasses an array of laws: blessings, laws related to the Land of Israel, laws of niddah (family purity) and mikvaot (rituals baths), and marriage law. After this is a section of responsa, then another section of legal material (“Part 2”), which, interestingly, roughly corresponds to what, later, the Tur would organize into the Orach Chaim section of the Arbaa Turim. The third and fourth sections of the work include legal decisions organized according to tractates of the Talmud: Bava Kamma, Bava Metzia, and Bava Batra, then Sanhedrin and Avoda Zara. These show that, despite the lack of formal codification, there was a flourishing Ashkenazi tradition of writing down halachic decisions.

At times, R. Yitzchak records contemporary situations, such as his mention of the Jewish badge decreed at the Fourth Latern Council of 1215 by Pope Innocent III. It occurs within a longer consideration of carrying on Shabbat, where he notes:

וכשהייתי אני המחבר בצרפת היינו מוליכים אופנים על הבגדים כי כן גזרו על כל היהודים בעת ההיא:

When I was writing in France, we would walk with badges on our clothing, because so it was decreed upon all the Jews at that time.

600 Years Later…

Probably due to its massive size, the Or Zarua was little copied and is mostly known to us from others’ citations of it, especially those of the Mordechai (a student of the Or Zarua) and the Hagahot Maimoniyot. The tome was abridged by one of R. Yitzchak’s sons, R. Chaim, in which form it circulated more widely and from which the work was often indirectly cited, including by Hagahot Asheri on the Rosh (by R. Yisrael of Krems, the great-grandfather of R. Yisrael Isserlein, the Trumat ha-Deshen). In these ways it entered the mainstream of Ashkenazi psak (legal rulings).

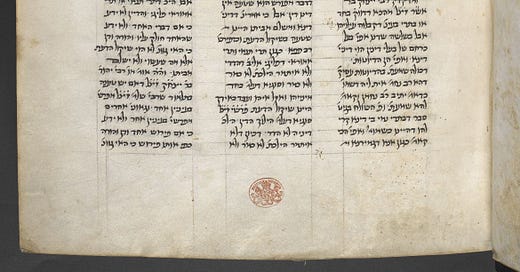

Or Zarua wasn’t published until 1862, when what we know as the first two halachic sections appeared in an edition published in Zhitomir (today’s Zhytomyr, Ukraine). The printed text of these volumes comes from one of only two extant full-but-incomplete manuscripts, Ms. Rosenthaliana 3 (“the Amsterdam manuscript”), the first page of which is pictured above. In 1887-90 another two volumes appeared, based on the second manuscript, British Library Ms. Or. 2860 (“the London manuscript”). These are the editions of the text you’ll find on Sefaria.

Our printed version of Or Zarua is but one snapshot of a gnarly text that subverts efforts to tame it into a closed book. (There are indications within the text itself that R. Yitzchak worked on it, revising and revisiting, for many years.) Like the peripatetic life of R. Yitzchak himself, the Or Zarua is a little extra: covering too much, in too many words, with too many versions. We do well to remember, and take heart, from its unruliness: it is a most human work, unbounded, overflowing, complicated, and precious.

Or Zarua Reads

A legend about the composition of the haunting Yamim Noraim piyyut U-netaneh Tokef has its earliest trace in Or Zarua, though other versions of the story circulated in medieval Ashkenaz. It forms a wonderful small case study of custom transmitted by R. Yitzchak ben Moshe, which you can read about here. The article is by Dr. Menahem Schmeltzer z”l, who passed away last Shabbat, and who I was exceedingly fortunate to have as my teacher of Hebrew paleography and codicology (the reading and physical analysis of manuscripts). Thank you to David Selis for reminding me about this gem of a microstudy.

For more on the Ashkenazi ethos of book composition, I highly recommend Dr. Ivan Marcus’s “Sefer Hasidim” and the Ashkenazic Book in Medieval Europe. It’s a expensive academic volume, though, so not everyone’s cup of tea (or budget). If you want to just dip in, you can read a thorough review by Dr. Amit Gvaryahu in Medieval Review.

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

I know that for those of us who’ve spent quality time with this book it’s going to be hard to let go, but no not really, because typing rashei teivot (Hebrew acronyms) into a browser tab at will is just so much faster. Kizur.co.il is your answer. It has a solid stable of rabbinic, modern, and technical acronyms (and tells you what field they’re from).

Or Zarua on Twitter

ICYMI

Next Week

The drama keeps on coming as we head to Rothenburg for a date with the Or Zarua’s leading student, Maharam.

Akshually: it was popularized well before Puccini by Henri Murger’s short stories, Scènes de la vie de bohème, first published in the late 1840s (rather unsuccessfully) and then adapted as a play (very successfully). That fin-de-siècle literature course I took in college really paid off, eh?

“The White,” possibly for more or less the same reason as Gandalf, or maybe for the River Elbe, which shares its consonantal letters with lavan.