Famous Hebrew Manuscripts: Masoretic Codices

📜 We kick off the new Famous Hebrew Manuscripts series with a look at significant copies of the Tanach (Bible) with vowels and cantillation marks.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. Today we embark on a journey through famous Hebrew manuscripts, not just famous for being pretty (i.e., illuminated), though we’ll have plenty of those special volumes too, but famous for being significant for textual transmission and the continuation of the Jewish tradition.

As we get started, a few framing notes. First, it’s been noted that calling this group of material objects “Hebrew manuscripts” is reductive: that they are more accurately termed “Jewish manuscripts,” given that they are written in a variety of languages used by Jews, including Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Judeo-Persian, Ladino, Yiddish, and more. I’ve used the more conventional term for recognizability, and indeed most of the manuscripts we’ll be exploring are written in Hebrew with some Aramaic. Secondly, many precious manuscripts have dramatic provenance stories, not infrequently involving mysterious disappearances and reappearances, back-alley deals, and other shady or questionable elements. Though I’ll make note of a manuscript’s provenance, I am not going to be focusing on this aspect of the manuscripts, but on their production, contents, and importance. Finally: not all famous manuscripts allow ready access to the public or even to specialized scholars, unfortunately, so I’m going to do my best to find usable images.

Audio (Paid Feature):

Listen to an audio version of this newsletter, read by me, here.

In this issue:

The Masoretes

All of the codices we’re exploring today emerge from the work of the Tiberian Masoretes, and all but one date from the Masoretic period, which arises in the 8th century, possibly earlier, and continues through the 10th. Known in Hebrew as baalei ha-masora, “masters of the Masora,” individuals working in this tradition were trained in the exacting method of recording the pronunciation, grammar, and chanting of classical Hebrew, all of which are absent in the consonantal text used for writing kosher Torah scrolls intended for ritual use. In addition, the Masoretes kept exact counts of the letters and words in the Tanach, passing along knowledge about how often certain words and phrases occurred in the corpus. There are indications that this reading tradition dates back to antiquity, well before the time of the Masoretic movement, as in this account in the Talmud:

לְפִיכָךְ נִקְרְאוּ רִאשׁוֹנִים סוֹפְרִים שֶׁהָיוּ סוֹפְרִים כׇּל הָאוֹתִיּוֹת שֶׁבַּתּוֹרָה שֶׁהָיוּ אוֹמְרִים וָאו דְּגָחוֹן חֶצְיָין שֶׁל אוֹתִיּוֹת שֶׁל סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה דָּרֹשׁ דָּרַשׁ חֶצְיָין שֶׁל תֵּיבוֹת וְהִתְגַּלָּח שֶׁל פְּסוּקִים יְכַרְסְמֶנָּה חֲזִיר מִיָּעַר עַיִן דְּיַעַר חֶצְיָין שֶׁל תְּהִלִּים וְהוּא רַחוּם יְכַפֵּר עָוֹן חֶצְיוֹ דִּפְסוּקִים

Therefore, because they devoted so much time to the Bible, the first Sages were called: Those who count [soferim], because they would count all the letters in the Torah, as they would say that the letter vav in the word “belly [gaḥon]” (Leviticus 11:42) is the midpoint of the letters in a Torah scroll. The words: “Diligently inquired [darosh darash]” (Vayikra 10:16), are the midpoint of the words in a Torah scroll. And the verse that begins with: “Then he shall be shaven” (Leviticus 13:33), is the midpoint of the verses. Similarly, in the expression: “The boar out of the wood [miya’ar] ravages it” (Tehillim 80:14), the ayin in the word wood [ya’ar] is the midpoint of Psalms, with regard to its number of letters. The verse: “But He, being full of compassion, forgives iniquity” (Tehillim 78:38), is the midpoint of verses in the book of Psalms.1

The Masoretes later developed a shorthand notation for these types of counts, known as the Masora Ketana (Masora parva in Latin, or Mp in academese), with the more detailed notes appearing in the Masora Gedola (Masora magna, or Mm.) For example, the Mp notation for a word that occurs only once throughout the Tanach (the technical term for this is a hapax legomenon) looks lie a lamed with a little dot over it, placed in the margin: ׂל, meaning ליתא or לית (Aramaic for “there isn’t any [other]”). Where a relatively rare word occurs several times, the beginnings of the other verses where it occurs are recorded in the Masora Gedola. Such precise counts ensured that the holy text was transmitted with extreme accuracy, as well as enhancing interpretative activity.

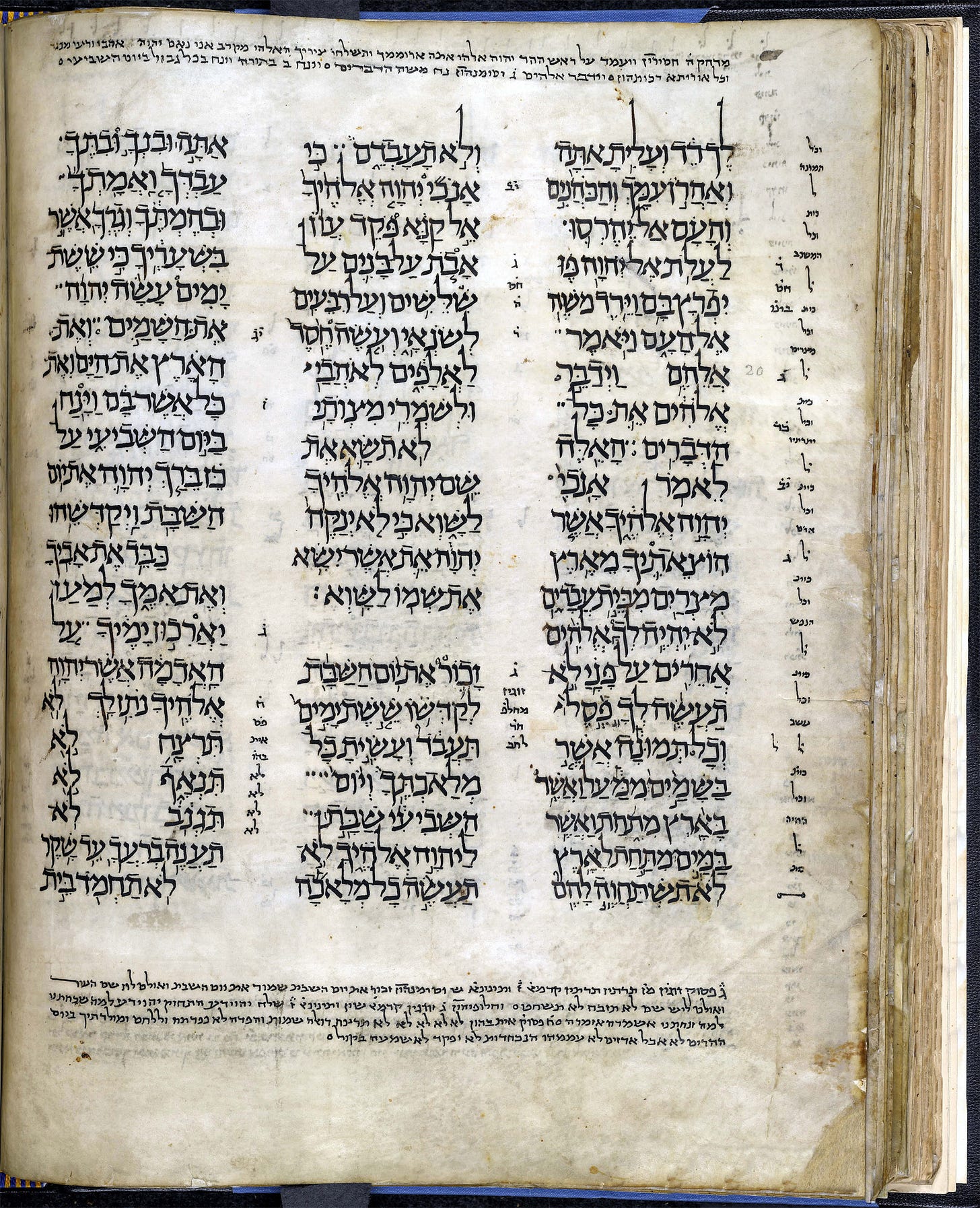

There were initially, it seems, two major schools of Masoretes, the Eretz-Yisraeli and the Bavli, the latter of which used supralinear markings (vowel marks that appear above the word). There is at least one surviving Masoretic codex with Babylonian vowelization, the Petersburg Codex of the Prophets, dated 916 (pictured above).2 A third school, the Tiberian, based in Tverya (Tiberius) in northern Israel, seems to have combined elements of both schools and was renowned for its precision, complexity, and uniformity. It was the Tiberian school that won out and become “our” vowelization system for Hebrew.

Within the Tiberian school, there were two famed dynasties of Masoretes: the Ben Asher family and the Ben Naftali family.3 The question of the relationship between these families and the Karaites is contested. There is compelling, though not entirely conclusive, historical evidence that the Ben Ashers were Karaites.4 (One scholar, writing for Oxford, squares the circle by saying that the Ben Ashers “may have had Karaite sympathies.”) What is clear is that during the early Middle Ages, including during the “silent” seventh century (the 600s CE) from which we have little surviving evidence, there was a robust “Biblicism” movement that functioned alongside the rabbinic movement that was busy redacting the Gemara. This movement, focused on Mikra (the twenty-four canonical books of the Written Torah), gave rise to both the Masoretes and the Karaites (Karaim, “readers” or “callers”).

Keter Aram Tzova: The Aleppo Codex

The most definitive Masoretic codex we possess is known Jewishly as כתר ארם צובא (Keter Aram Tzova, “the Crown of Aleppo”) and to academics as the Aleppo Codex. It was completed c. 930 in Tverya, with the consonantal text written by the scribe Shlomo ben Buyaa and the Masoretic symbols and notes added by Aharon ben Asher, a fifth-generation scion of the famed Ben Asher family. From Tverya the codex went to a Karaite synagogue in Jerusalem, from which it was apparently looted by Crusaders in 1099 and redeemed by a synagogue in Fustat (Old Cairo), where it acquired the appellation al-Taj, “the Crown.”5 Around 1375, a descendent of Rambam seems to have moved it from Cairo to Aleppo, where it remained, whole, until 1947. At that time, some 40% of the Keter, including most of the Torah, disappeared during anti-Jewish riots that broke out following the announcement of the UN Partition plan, which allocated land in Eretz Yisrael to Jews. During the Keter’s six-hundred-year tenure in the Aleppo Jewish community, it was closely guarded, though a few modern scholars, including Umberto Cassuto, were granted access. The remaining part of the codex was smuggled into Israel in 1958, but, under somewhat murky circumstances, was not immediately made available for scholarship.

The reasons for the signal importance of Keter Aram Tzova are several, predicated on its antiquity and the chain of authentication of its Masoretic notes. Until 1947, it was the oldest known complete codex of the Tanach with nikud, taamim, and Masoretic notes. But more than that, its Masora had been authenticated by a member of the Ben Asher family. There is a near-contemporary book, Sefer ha-Chilufim (“Book of Differences”), which records the (generally tiny) disagreements between the Ben Asher and Ben Naftali schools. The Keter almost perfectly aligns with the Ben Asher tradition, in contradistinction to the Leningrad Codex (on which, more below).

An influential indicator comes from the Great Eagle himself, Rambam. The following description of an authoritative codex, which he used to correct his own copy of the Tanach, matches well and is presumed by most scholars to refer to Keter Aram Tzova:

וְסֵפֶר שֶׁסָּמַכְנוּ עָלָיו בִּדְבָרִים אֵלּוּ הוּא הַסֵּפֶר הַיָּדוּעַ בְּמִצְרַיִם שֶׁהוּא כּוֹלֵל אַרְבָּעָה וְעֶשְׂרִים סְפָרִים שֶׁהָיָה בִּירוּשָׁלַיִם מִכַּמָּה שָׁנִים לְהַגִּיהַּ מִמֶּנּוּ הַסְּפָרִים וְעָלָיו הָיוּ הַכּל סוֹמְכִין לְפִי שֶׁהִגִּיהוֹ בֶּן אָשֵׁר וְדִקְדֵּק בּוֹ שָׁנִים הַרְבֵּה וְהִגִּיהוֹ פְּעָמִים רַבּוֹת כְּמוֹ שֶׁהֶעְתִּיקוּ וְעָלָיו סָמַכְתִּי בְּסֵפֶר הַתּוֹרָה שֶׁכָּתַבְתִּי כְּהִלְכָתוֹ:

The scroll on which I relied on for these [Masoretic] matters was a scroll renowned in Egypt, which includes all the 24 books. It was kept in Jerusalem for many years so that scrolls could be checked from it. Everyone relies upon it because it was corrected by Ben Asher, who spent many years writing it precisely, and [afterward] checked it many times. I relied [on this scroll] when I myself wrote a Torah scroll according to the law.

Rambam, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Sefer Torah 8:4

Keter Aram Tzova is currently owned by the Ben Tzvi Institute (Ms. 1) and displayed at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, where one quire6 is on view in Heichal ha-Sefer (the Shrine of the Book) alongside the Dead Sea Scrolls. It has been expertly photographed by Ardon Bar-Hama, who has photographed many of the world’s treasures on paper, with the high-resolution images available on his website. There is also a side-by-side image and transcription available on the website of Bar-Ilan University’s Mikraot Gedolot ha-Keter website. This critical edition of the Tanach with commentaries, being published by Bar-Ilan University Press, is based on Keter Aram Tzova, using other Masoretic codices to inform the rendering of the missing portions of the Torah.

The Leningrad Codex (Codex Leningradensis)

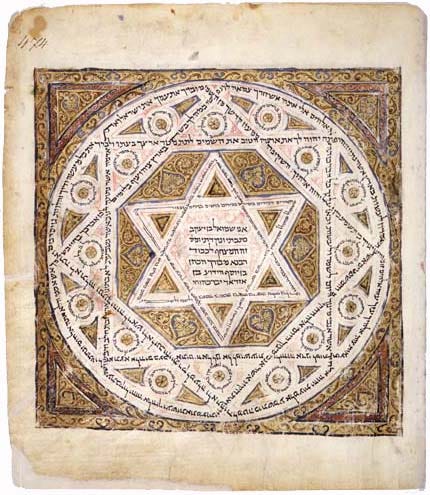

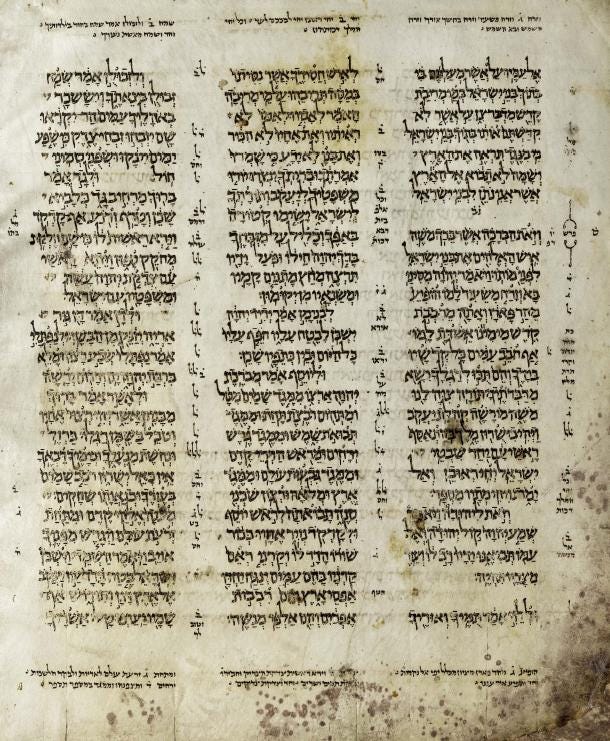

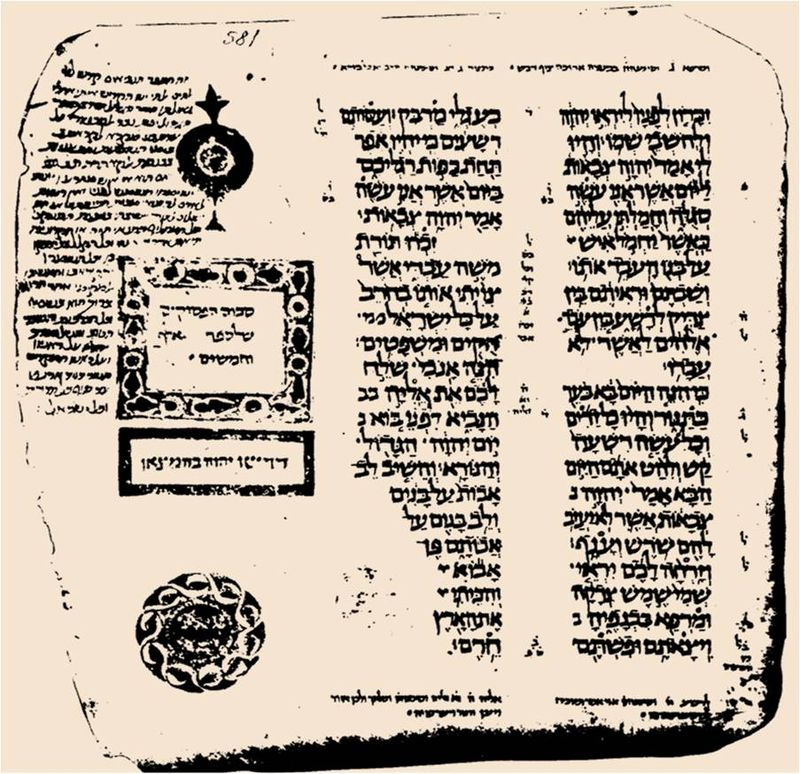

Since the lamentable losses from Keter Aram Tzova in 1947, and until the resurfacing of the heretofore privately-held Sassoon Codex (on which, more below), the Leningrad Codex had won the distinction of oldest complex Masoretic codex in the World.7 Written in 1008/9, it was both written and vowelized in Cairo by a scribe named Shmuel ben Yaakov, according to its colophon (pictured above, first image). There is no direct evidence that it was approved or handled by a member of the Ben Asher family, and there are numerous (though small) erasures and discrepancies that indicate that it was corrected towards the Ben Asher tradition after its writing. That being said, it remains an incalculably precious, pristine early textual witness.

The Leningrad Codex was purchased in the 19th century by the Crimean Karaite book collector Abraham Firkovich, who brought it to Russia, where, eventually, it was inadvertently locked behind the iron curtain along with a number of other early, substantial Masoretic codices.8 However, in the 1930s in was lent out to the University of Leipzig where it became the basis for the 1937 Biblica Hebraica (BHK), the third edition of a critical text of Tanach used by academic Bible scholars (earlier editions had been based on the early printings of the Rabbinic Bible from the 16th century). The Biblica Hebraica has since been updated, the fourth edition being the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS, available on Amazon) and the latest edition, the Biblia Hebraica Quinta (BHQ, volumes available on Amazon). Until the 1990s, few Jewish scholars had access to the Leningrad Codex, but this changed after the fall of the USSR when it was photographed, with the images being disseminated in the West. Jewish scholarship still tends to prefer the Aleppo Codex.

The Sassoon Codex (Sassoon Ms. 1053)

The Sassoon Codex (Sassoon Ms. 1053), which has long been privately held, recently resurfaced after its latest 40 years of private ownership (it was, however, digitized in its entirety: click the link above). Its Masora does not align neatly with the Ben Asher tradition, which, in this case, likely attests to it having been written early. Last week, offered at auction by Southeby’s, Codex Sassoon was purchased for USD 38.1 million by an American Jewish diplomat on behalf of the Anu Museum (formerly Beit Hatfutzot) in Tel Aviv, where it was previously on display (and from which the video above comes).

Radiocarbon dating undertaken by its previous owner, presumably recently, revealed the manuscript to be approximately 1,100 years old, which dates it to the 9th or 10th century, roughly the same age, possibly older, than Keter Aram Tzova. The Sassoon Codex is nearly whole, missing only twelve leaves.

Other Masoretic Codices of Note

The Cairo Prophets Codex (Codex Cairensis, Karaite Synagogue of Cairo Ms. 34) seems at first glance to be overlooked. The codex bears nearly the whole of Neviim, the most voluminous section of Tanach, is purportedly dated 895/6, which is quite early—and, according to its colophon, was written by Moshe ben Asher himself (the grandfather of Aharon, who added the Masora to Keter Aram Tzova). The Cairo Codex also has a provenance story similar to that of Keter Aram Tzova. However, subsequent research has demonstrated that its Masora was added later, probably in the 11th century, and its fidelity with the Ben Asher tradition is disputed.

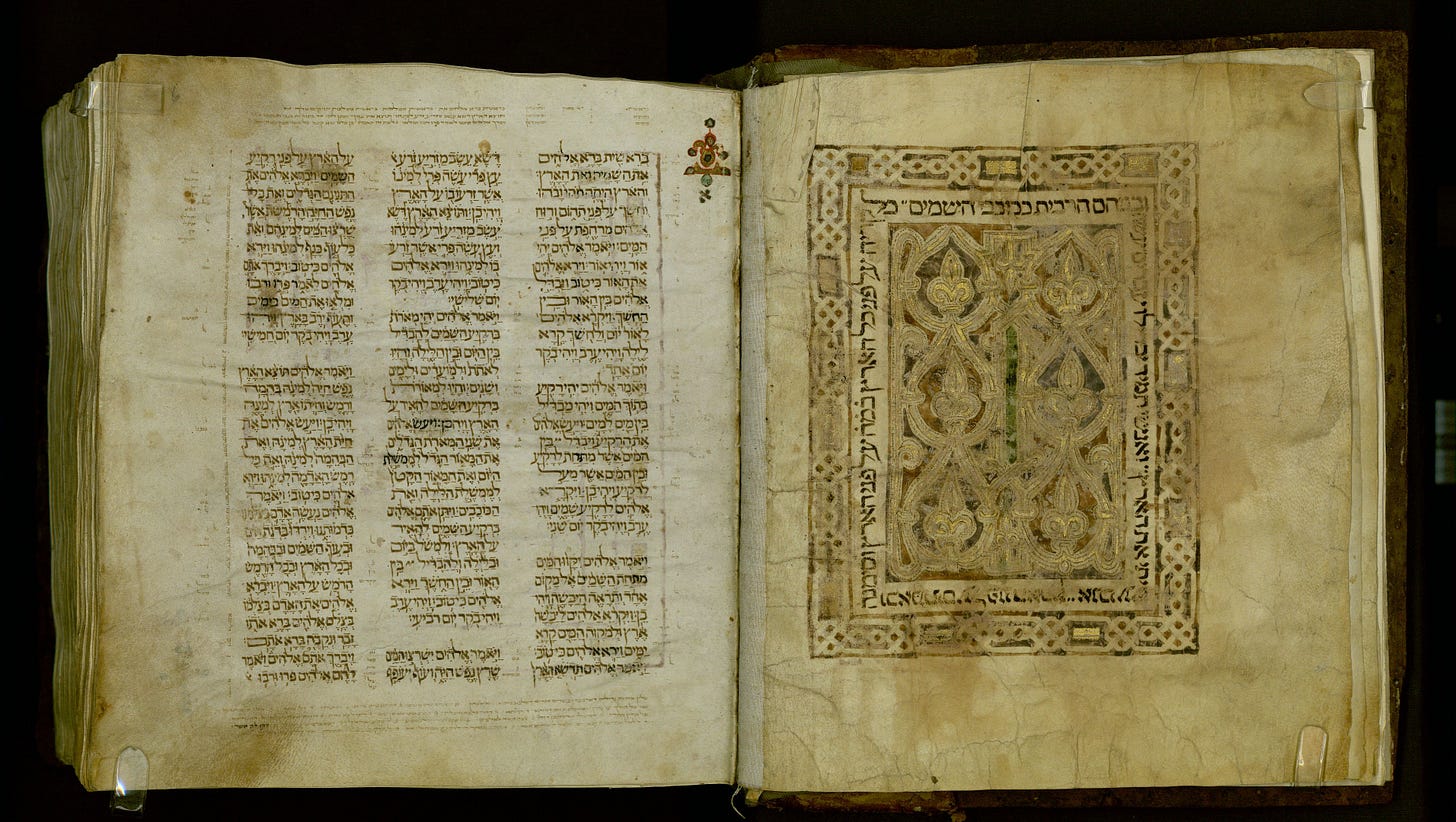

There are, somewhat confusingly, two importance codices of the Torah known as Keter Damesek (“the Crown of Damascus,” both sometimes anglicized as the Damascus Pentateuch). The older codex, dating from c. 1000, is now National Library of Israel Ms. Heb. 24°5702. The other Keter Damesek, now National Library of Israel Ms. Heb. 24°790, is an interesting later codex, created and illuminated in Burgos, Spain in 1260 but with full Masoretic notation.

Another two important textual witnesses to the Torah missing in Keter Aram Tzova are the London Codex (British Library Ms. Or 4445), a 10th-century manuscript with 11th-century (or later) Masoretic notes, with affinities to the aforementioned Petersburg Codex but bearing Tiberian markings; and the Washington Pentateuch (Torah), dating from 11th century (with 12th century repairs), which is now owned by the Museum of the Bible.

These are the major textual witnesses in our possession to the text of the Tanach, and they are, incredibly, available online for our perusal whenever a interesting text question piques our collective curiosity.

Masoretic Resources & Reads

If you’d like to learn how to use the Masoretic notes, Ancient Jew Review has how-to articles on the BHS edition and its successor, the BHQ, which are printed versions of the Leningrad Codex. They’re good for getting a general overview of masoretic notations, too.

Lots of recent writing about the ongoing drama of the Aleppo Codex: “The Continuing Mysteries of the Aleppo Codex,” Tablet; “That in Aleppo Once,” JRB; and Matti Friedman’s book, The Aleppo Codex: A True Story of Obsession, Faith, and the Pursuit of an Ancient Bible (2013).

Here is the informative article on the Codex Sassoon published by Southeby’s.

Next Week

Next time, we’ll look at important manuscripts of the Mishnah and Tosefta.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective.

There are fascinating deliberations about what these particular counts mean and how they’re figured, but we’ll leave those for another newsletter.

There is another set of good-quality photos here. Many examples of the Babylonian system turned up in the Cairo geniza, but given that we use Tiberian vowels, our most important exemplars for the Masoretic text derive from the Tiberian school.

Here’s a Twitter thread I wrote on the last of Ben Naftali, the lesser-known family.

A robust amount of documentary material from the Cairo geniza attests to the presence in Fustat of a prominent Karaite family called Ben Asher; in addition, R. Saadia Gaon polemicized explicitly against a Karaite by the name of Ben Asher. On the other hand, the presence of Karaite Ben Ashers in Tverya is not otherwise attested.

The manuscript bears a mark attesting to its redemption, and fits the description in a recovered list of goods ransomed by Crusaders, so the evidence fits together, though it’s not definitive. There is also debate about whether the synagogue where the Keter was housed was Rabbinic or Karaite.

A quire is a booklet; a codex is generally bound from multiple quires.

Including National Library of Russia Mss. EVR I B 19a, EVR II B 10, EVR II B 17, EVR II B 39, EVR II B 59, EVR II B 225, and there are others in Russia as well.

Amazing stuff! I’m proud to be a subscriber