Illuminated Medieval Haggadot

📜 We continue exploring illuminated Passover haggadot with blockbuster manuscripts from Ashkenaz and Sefarad.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. This week in the Famous Hebrew Manuscripts series, we have a visual feast of medieval illuminated haggadot from Ashkenaz and Sefarad. We’ll also briefly explore what we know about why and how they were produced.

And, some book news: the Rishonim book is underway! I returned from a writing retreat last week with an introduction and a chunk of chapter one (on the Geonim) written. Stay tuned for more updates as I write.

In this Issue:

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here (and an archive of all audio editions here.) I’m setting up a makeshift recording studio in the garage (!) so I can record audio for the earlier newsletter, too, so those will be forthcoming over the summer.

Like Machzorim, illuminated Passover haggadot are a phenomenon of the later Middle Ages, beginning to appear around the year 1300 and continuing in full force through the advent of printing (even continuing, to a lesser extent, after the wide-scale adoption of moveable type). Unlike Machzorim, however, there is a distinct and robust Sefardi tradition of producing such illuminated books for ritual use alongside an Ashkenazi-Italian school.

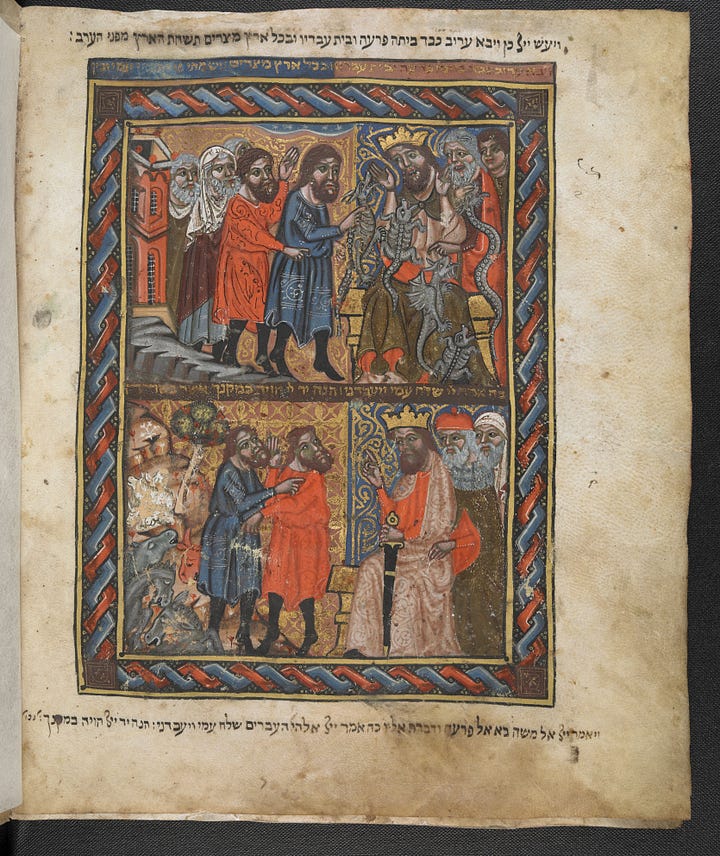

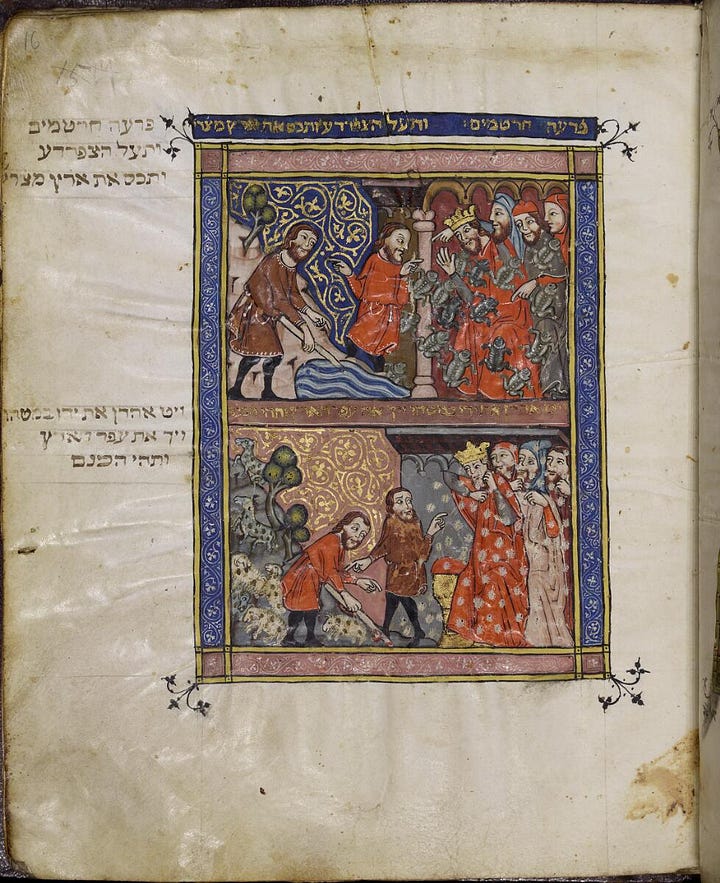

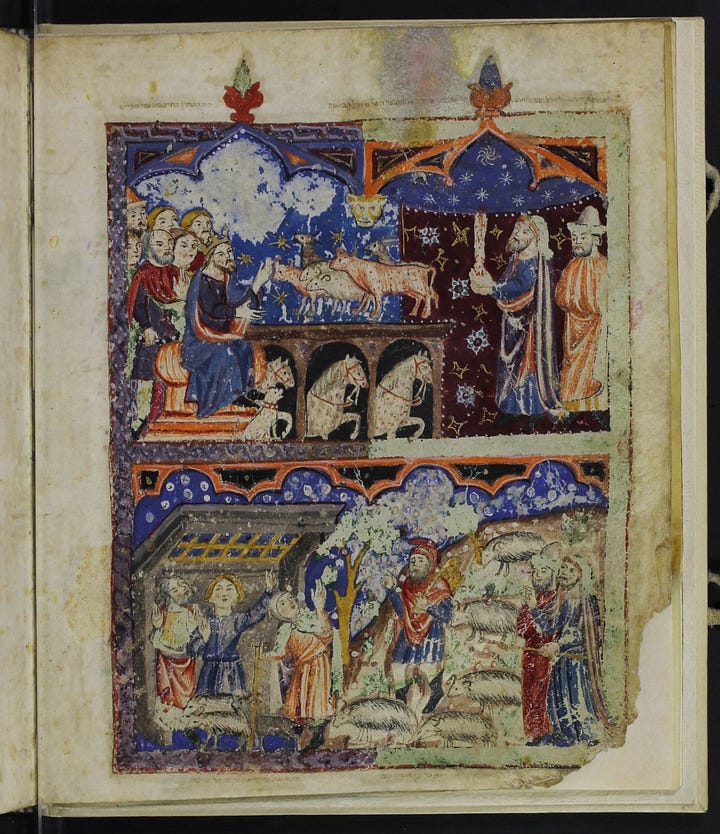

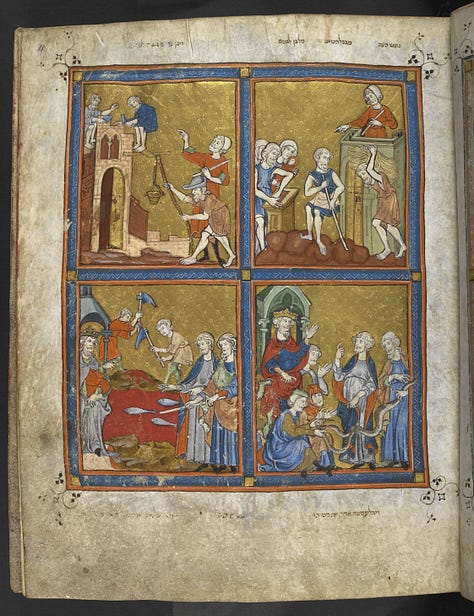

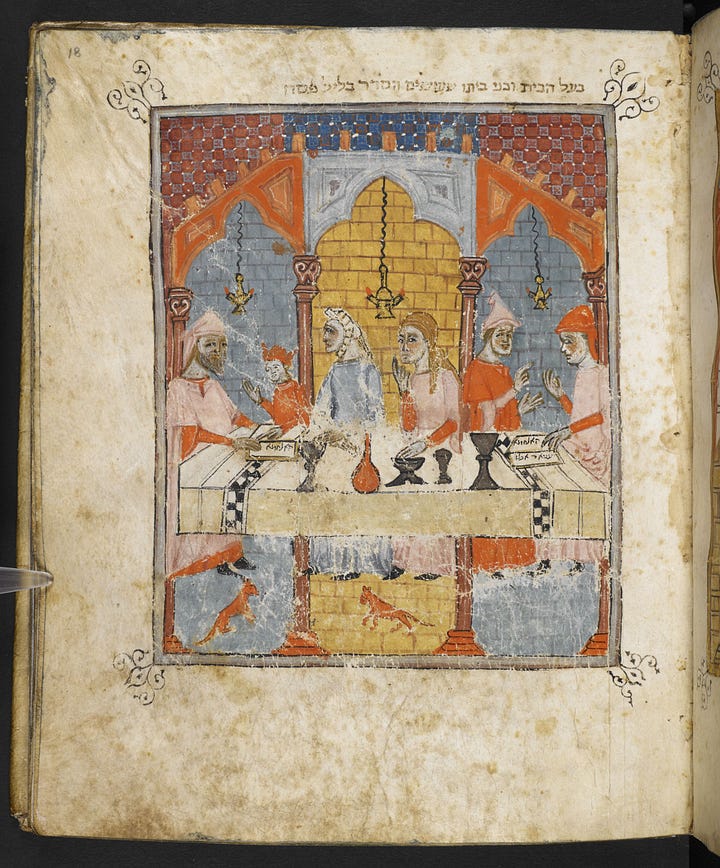

There are common features, as well as disparate foci, between the illustrated haggadot of Sefarad and Ashkenaz. For instance, both tend to include depictions of Biblical scenes as well as images of contemporary Seder meals. However, the Sefardi illuminated haggadot typically devote more space, especially in lush opening panels that precede the text, to Biblical imagery, usually including the exodus story from Sefer Shemot and often also stories of the patriarchs, with a focus on Yosef, from Bereshit. These Biblical panels typically show elements drawn from traditional midrashic scriptural exegesis. Some Sefardic haggadot go all the way back to creation and some include scenes from the remaining books of the Torah as well. Meanwhile, Ashkenazi haggadot feature more detailed depictions of contemporary Passover preparations, such as baking matzah. Ashkenazi haggadot also tend to include piyut and other liturgical or even halachic material.

It is likely that the production, beginning in the thirteenth century, of Christian books for ritual use or personal enjoyment, such as psalters (books of psalms), breviaries (liturgical books of daily prayer rites), books of hours (abbreviated breviaries), and picture Bibles, influenced Jewish book arts of the period. In particular, the miniature scenes produced in northern France seem to have had a decisive influence, even upon Spanish illumination. Scholars, in particular Katrin Kogman-Appel, have argued for the use of motif books, or standard iconographical exemplars, in the production of Sefardi haggadot and illustrated Hebrew Bibles.

Below, I’ve attempted to cover the most famous and sumptuous of late medieval Pesach haggadot. It seems shocking, but there are relatively many lesser-known illuminated haggadot that are understudied and exhibited, sometimes secreted away in private or minor collections. So, this is certainly not an exhaustive, but hopefully a reasonably comprehensive, account of this meaningful genre.

Ashkenazi Illuminated Haggadot

Perhaps the best-known (and weirdest) Ashkenazi haggada of all is the Birds’ Head Haggada, whose mysteries we delved into last week. Unfortunately, for the rest of the famed Ashkenazi haggadot, good images are not as available as for Sefardi haggadot. So, this section will be mostly descriptive with links to where some images are available.

The Darmstadt Haggada

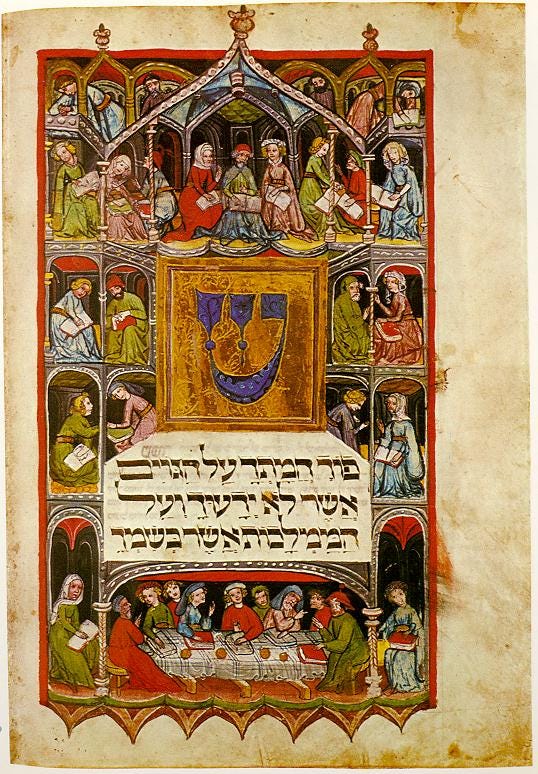

Dating from c. 1430, the colorful, finely detailed Darmstadt Haggada (Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Darmstadt Cod. Or. 8, also here) contains an number of unusual illuminations, including a fountain of youth, a hunting scene, and, notably, women with open books on their laps, participating in the seder. It may be that these are influenced by contemporary German or northern French books arts—its scribe hailed from Heidelberg. Meyrav Levy has also suggested that it may be intended to depict an Olam ha-Ba (World-to-Come), alternate reality.

The Second Nuremberg Haggada and the Yahuda Haggada

Despite the nomenclature, the Second Nuremberg Haggada, so called to distinguish it from another Ashkenazi haggada previously held in the Stadtbibliothek (State Library) of Nuremberg, is closely related not to the First Nuremberg but to another anonymous haggada called the Yahuda Haggada (Israel Museum, Jerusalem Ms. B55.01.0109). (The First Nuremberg Haggada, exquisitely penned, was written by the well-known scribe Yoel ben Shimon, who was active first in Germany and then in Italy and wrote some twelve extant manuscripts, including several haggadot; see the next section.) Unfortunately, I couldn’t find usable images, but click over on the links above to see proprietary images of these magnificent manuscripts.

The Washington Haggada

Completed in 1478 by the aforementioned master scribe and artist Yoel (Feibush) ben Shimon, the Washington Haggada (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., USA Hebr. Ms. 181, also here) features delicate decorate figures, especially filigreed panels. It was completed in Germany and later made its way to Italy and finally, to the United States. Again, images are not available for use, and the site appears to have broken links, but click over for a glimpse.

The First Cincinnati Haggada

The First Cincinnati Haggada (Hebrew Union College Ms. 444, also here) is a late medieval manuscript penned by the scribe and leatherworker Meir Jaffe in Heidelberg, c. 1480-1490.

(The Second Cincinnati Haggada, HUC Ms. 444.1, dates from 1716/17, centuries later and firmly in modernity; interestingly, its illustrations are based on woodcuts included in an early printed haggada.)

Spanish Illuminated Haggadot

Starting around the year 1300 in Catalunya (the northeast of Spain), we see a bumper crop of decorated haggadot, some clearly coming from the same atalier. In some cases, the illumination is overwhelming similar to that of other known haggadot; in others, there are various stylistically distinct features. Many are written in Sefardic square script.

The Hispano-Moresque Haggada

Produced c. 1300, the Hispano-Moresque haggada has a unique illumination style, though its subject matter is conventional. (“Moresque,” or “Moorish,” is an older, and slightly pejorative, adjective meaning Islamic.) Note the castle frame on the left above, which reappears in many panels and seems to depict the Catalonian landscape.

The Prato Haggada

Also created c. 1300, this composite manuscript (JTS Ms. 9478) begins with the Sefardi version of the haggada and omits Birkat ha-Mazon (the blessing after the meal) and Hallel Gadol (Tehillim 136). A large number of pages were added later, possibly to be localized to 16th-century Italy, with some left unfinished. Among its iconography are mythical creatures.

The Sarajevo Haggada

Among the most iconic and enigmatic of the Sefardi illuminated haggadot is the Sarajevo Haggada, held by the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo and dating to the 14th century. The reason that it’s enigmatic is because of its relatively remote location, close guardianship, and strange provenance story. It is difficult to find images of the Sarajevo Haggada, but you can see a number of them, including unfinished pages, on Google Arts and Culture.

The Rylands Haggada and the Brother Haggada

Scholarship has established that these two haggadot are the product of the same Catalonian workshop, operating c. 1330. The Rylands (University of Manchester Ms. Heb. 6, also here) was more widely known initially—hence its “brother” haggada was so named—but it appears that the Brother Haggada (British Library Ms. Or. 1404, also here) is actually the earlier of the pair. The Borther Haggada is somewhat less refined in its illustrative technique. (You can compare the identical scenes in the images above; the Brother is on the left and the Rylands on the right.) There may also be a relationship between these haggadot and the Sarajevo Haggada.

The Kaufmann Haggada

The beautiful 14th-century Kaufmann Haggada (Hungarian Academy of Scienes, Budapest Ms. Kaufmann A 422, also here) includes detailed scenes, gold-leafed initial words, and large, clear script. It shows marked evidence of wear and tear: that is to say, actual use at many a Pesach Seder. This, charmingly, includes evidence of children’s doodles in the margins.

The Barcelona Haggada

Similar in style to the Kaufmann Haggada, the Barcelona Haggada (British Library Ms. Or. 14761, also here), c. 1325-1350, includes many depictions of animals, birds, and hybrid creatures. It also has number of liturgical additions related to the Pesach, more commonly seen in Ashkenazi haggadot, but here according to the Sefardi custom. Some Provençal liturgy was later added.

The Golden Haggada

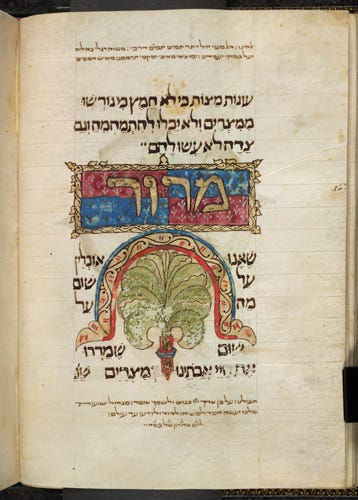

The stunning Golden Haggada (also here), c. 1320-1330, is replete with gold-leaved scenes of the exodus, a typical focus for Sefardi illuminated haggadot. Here the all-gold backgrounds give it a sumptuous air. In addition, initial words receive elaborate decoration. The matzah page, above right, shows the enduring influence of Islamic art in Christian Spain.

The Sister Haggada

The Sister Haggada (British Library Ms. Or 2884, also here) is so called because it is the “sister” of the Golden Haggada, although it is noticeably less elegant. It contains a particularly interesting miniature depicting a woman tasting the ritual foods of the seder, in contrast to the men, who are portrayed as reading from haggadot. The scholar Julie A. Harris suggests two possible meanings arising from the portrayal of the woman in this seder scene: first, it emphasizes the connection of the feminine with the senses, and second, the woman’s direct gaze and her centrality may indicate that the haggada was explicitly designed with the presumption that women would use it.

Reading Recommendations

Everything is Illuminated: Mining the Art of Illustrated Haggadah Manuscripts for Meaning on the Seforim Blog.

Haggadot Highlights at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

There are wonderful books out there about illuminated haggadot, but most are prohibitively expensive. If you’re curious about the next chapter in haggada history, that of printed haggadot, there’s (the still-pricey but not totally unfathomable) Yosef Yerushalmi’s Haggadah and History (JPS, 2005).

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective.