The Mysteries of the Birds' Head Haggada

📜 In the first of two newsletters focused on illuminated Passover haggadot, we take a look at medieval Ashkenazi aniconism and the perplexing phenomenon of depicting humans as animal-headed.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. Illuminated haggadot don’t get going until the central Middle ages, but once they do, they’re amazing creations. Though still fundamentally rare material objects, there are a number of lavish surviving copies, enough to split into a two-part newsletter. Today, we’ll take a look at aniconism (and its discontents) as it emerged in medieval Ashkenaz, that is, outside of the Islamicate world where, aside from Persian art, aniconism was the cultural norm. Then, we’ll take a deeper dive into the mysteries of the so-called Birds’ Head Haggada.

In this issue:

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here (and an archive of all audio editions here.)

The Depiction of Humans in Art: R. Efraim of Regensburg’s Responsum

A central question in Jewish art history is Judaism’s relationship to the figurative image, which the Second Commandment proscribes—although precisely what it proscribes is a matter of discussion among the poskim (halachic decisors). The prohibition on figurative art, or aniconism (as in an, non-, and icon) was a cultural norm in Islam, and Jews in Islamicate society generally followed suit, with the exception of those in the Persian milieu, where iconism was practiced. The halachic discussion considers whether the images must be three-dimensional (i.e., sculptural, either engraved or protruding), whether human likenesses, even flat drawings, are okay, whether and which animals may be depicted, and more such topics.

It has been suggested by the scholar Dr. Zsofia Buda that the particular manifestation of animal-headed humans in Ashkenazi manuscript art is a local practice influenced by the ascetic-pietistic movement in post-Crusades Germany known as Chasidei Ashkenaz. This movement emphasized personal piety and modesty, especially in relation to viewing women. Specifically, she notes the responsum of R. Efraim of Regensburg, cited by the Maharam of Rothenburg, which issues a middle-ground ruling. (It relates to embroidered or otherwise decorated Torah mantles and other synagogue textiles.)

השיב רבי׳ אפרים מרעגנשפורק את רבינו יואל הלוי בספר אבי״ה בסי׳ אלף ומ״ט.

תרי. על צורות עופות וסוסים [שציירו בבית הכנסת] ששאלת אם מותר להתפלל שם ובאת לדמות לצורת לבנה ואנדרטא א״כ הי׳ לך לשאול אם אסור בהנאה וכע״ש להתפלל שם אבל אינו דומה לטבעת שיש עלי׳ ותם [שהוא] דמות צלם פרצוף אדם או דמות [חמה] ולבנה ודרקון שעובדי׳ להן… אבל צורות עופות וסוסים אין עובדי׳ להן אפי׳ כשהן תבנית [בפני] עצמן כ״ש כשהן מצויירי׳ על הבגדים [ותניא ע״ז מ״ב ע״ב] כל הפרצופי׳ מותרי׳ חוץ מפרצוף אדם.Thus replied Rabbenu Efraim of Regensburg to Rabbenu Yoel ha-Levi in Sefer Raavia, no. 1049: What is the reason that it is permitted? With regards to figures of birds and horses [that were painted in synagogues] that you asked about, whether it is permitted to pray there, you came to liken them to images of the moon or of a man. As such, it makes sense to ask whether it is forbidden to enjoy benefit from them or to pray there. However, these are not similar to a ring with has upon it the likeness of the image of a human face or the likeness of [the sun] and the moon and a dragon, which people worship… But the figures of birds and horses which people do not worship, even when they are cast on their own and all the more so when they are illustrated upon cloths [as taught in Avoda Zara 42b], all faces are permitted except for the face of a human.

Teshuvot Maharam of Rothenburg (Prague, 1608), no. 610.

R. Efraim draws a distinction between figures of things that are worshipped, including animals such as the dragon, but allows pictures of everyday animals that are not, to his knowledge, the object of worship, such as birds and horses. He categorizes the human face as belonging to the forbidden class. Thus, it would seem that a workaround, allowable according to R. Efraim, could be to depict people with the heads of, say, birds, thereby avoiding the drawing of the human visage. This practice is known from other contemporary Ashkenazi manuscripts, though it soon ebbs, perhaps along with the Chasidei Ashkenaz movement.

Introducing the Birds’ Head Haggada

One of the most iconic illuminated Hebrew manuscripts is surely the mysterious Birds’ Head Haggada, which depicts human figures with what appear to be—you guessed it—birds’ heads. (A closer look tells a more complicated story, which we’ll get into below.) It was produced in southern Germany c. 1300.

The manuscript is also distinguished for being a stand-alone haggada; earlier, haggadot were included within machzorim (holiday prayerbooks), and it’s not until the later Middle Ages that they become independent objects. Featuring crisp Ashkenazi square script written by a known scribe (his name was Menachem), vowelization, and colorful illustrations, the Birds’ Head Haggada, for all its weirdness, has become a hallmark of Ashkenazi visual culture. (It even boasts a modern, and quite charming, pop-up version.)

Why Are Humans Depicted as Birds (or Griffins)?

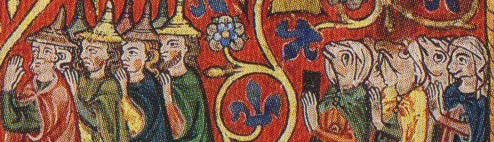

Medievalist and art historian Dr. Marc Michael Epstein has pointed out that the figures in the Birds’ Head Haggada may not actually be bird-headed, but griffin-headed. A griffin is a mythical chimera creature that is part eagle and part lion, and the beards and manes on the male figures seem, indeed, leonine.

The depiction of Jews as griffins would seem to indicate nobility and grandeur, befitting the commission of a wealthy patron, as opposed to a negative depiction, as some scholars maintain.

In addition, Epstein notes that Datan and Aviram, identified in midrash with the taskmasters who cooperated with the Egyptians,1 are depicted with blank faces (see the image in the previous section). Here, the blank ovals clearly intend to blot out the likeness of these wicked personas, in contradistinction to the noble Jews.

Zoocephalic humans are not unique to the Birds’ Head Haggada; the Tripartite Machzor, which we encountered last week, and the Ambrosian Bible, an early, 13th-century Ashkenazi illustrated Tanach (Ambrosiana, Milan Mss. B.30–32 Inf.), also include animal-headed human figures.

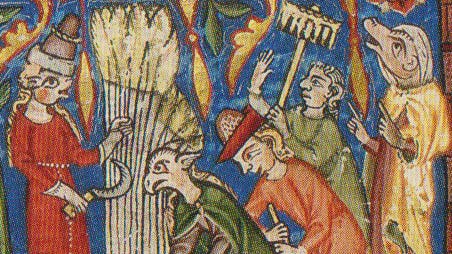

Here are close-up details of the above images from the Tripartite Machzor; note the men with human heads wearing distinctive caps and the women depicted with animal heads:

It has been suggested that depicting women thus is an attempt to prevent an inappropriate male gaze upon the feminine figure, or else as a means of ennobling the women, who do not otherwise bear a distinctive marker like the men in their caps. (There is also considerable debate about whether this so-called “Jew’s Hat” has historical basis in sartorial practice of the time in light of Church regulations.) On the one hand, the gendered depiction demonstrates that human figuration was not absolutely proscribed, and it might additionally indicate that zoocephaly was an ennobling practice rather than a diminishing one.

In the Ambrosiana Bible, we see, interestingly, humans depicted as various kinds of animals, right alongside actual animals:

Note the actual griffin and the explicit lion-headed king in the Ambrosiana Bible:

Ultimately, we do not have definitive answers to why humans were depicted with animal heads in later medieval Ashkenaz, nor do we know the identity (Jewish or not) of the artists who produced them. But we do see a definite, if local, practice that seems to be influenced by Jewish law and, perhaps, pietistic practices.

Related Readings

One of my favorite books in medieval Jewish studies generally and on Jewish art in particular is the beautiful and insightful Skies of Parchment, Seas of Ink: Jewish Illuminated Manuscripts, edited by Marc Michael Epstein, et al. and featuring collaborative scholarship by experts in the area. (It includes Epstein’s take on the Birds’ Head Haggada.)

If you’re looking for an introductory book on Hebrew illuminated manuscripts that is not overly technical but provides detail and illustrations, I recommend Hebrew Manuscripts: A Treasured Legacy by Benjamin Richler.

On Jewish aniconism, Kalman Bland’s The Artless Jew: Medieval and Modern Affirmations and Denials of the Visual is a wonderful and thought-provoking read.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective.

Also mentioned in Megillah 11a.