Petachia of Regensburg: A Medieval Ashkenazi Jew Travels to the East

🗺️ Petachia, from a Tosafist family, traveled overland through Eastern Europe to reach Babylonia (Iraq) and the Land of Israel, leaving behind notes, heavily worked by later hands, about his travels.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. We continue our exploration of Jewish aliyah to the Land of Israel in the premodern era with R. Petachia of Regensburg, who might be called the Ashkenazi Binyamin of Tudela. Below, we’ll take a look at his particular goals for his travels, the way the account of his adventures came together, and the many details he preserved about Jewish holy sites in Crusader Eretz Yisrael.

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here.

Joshua Prawer, the distinguished historian of the Crusader kingdoms of the Land of Israel, counts ten travel narratives, of varying lengths, attesting to Jewish life in the Crusader period.1 Of these, the account of Binyamin of Tudela is one, and our subject today, the account of R. Petachia of Regensburg, is another. That is to say, they are part of a group of extant travel narratives, themselves but the survivors of the larger phenomenon of Jewish travel to the Land of Israel. Presumably, few travelers both wrote down their tales and were fortunate enough to have their accounts preserved. R. Petachia is one such notable writer.

Petachia and his Sivuv

R. Petachia of Regensburg in Germany (also called in Hebrew Ratisbon or in French Ratisbonne) is known to have come from a family of Tosafists, the company of scholars who produced the dialectical Talmud commentary that now flanks the far side of the Talmud text on the daf (page)—and has since its first printing. Petachia’s brother was R. Yitzchak ha-Lavan (“the White”), a Tosafist who studied under, among others, the famed Rabbenu Tam, grandson of Rashi, in France. (It has been suggested that R. Yitzchak, or perhaps their father R. Yaakov, also a Tosafist, got the moniker “ha-Lavan” from the similar-sounding River Elbe, or else from his white-haired visage). Both brothers were active in Regensburg and Prague during different periods of their lives, and are sometimes known as Bohemians.

Around the year 1175, R. Petachia, who was a person of means, departed from Prague on a journey to pray at the graves of notable Jews, particularly Biblical figures, in the East. He traveled overland through Poland and the Kievan Rus’ (Ruthenia) down through the Crimea into Tartary, Khazaria (about which, see here), Ukraine (which Petachia called Kedar), Armenia, and Kurdistan. These locations, for which we have relatively few Jewish sources and are of great historical interest, are not treated in any detail in the account. Rather, the narrative of R. Petachia’s travels concentrates on his experiences in Babylonia (Iraq) and in the Land of Israel, including his visiting of graves and holy sites as well as remarks about contemporary Jewish communities. He seems to have returned to Europe by sea, sailing to Greece and then proceeding by land back to Prague, eventually reaching Regensburg.

It was in Regensburg, that R. Petachia must have dictated, likely from notes he had taken during the journey, his adventures to his trusted friend, R. Yehuda he-Chasid of the Chasidei Ashkenaz, a pietistic movement that grew up in Germany following the First Crusade violence that decimated medieval Ashkenazi communities. This is made clear by the third-person narration in the account; the writer of the version we have today is identified by a third voice as R. Yehuda he-Chasid. Whether, as Prawer suggests, the third editor was present during the oral history-taking, or whether he simply had before him a written version of R. Petachia’s account, he shows himself in a section of the text in which Petachia encounters a master astrologer in Nineveh (Mosul). The astrologer, one R. Shlomo, revealed to Petachia the date of the coming of the mashiach (messiah), “but Rabbi Yehuda he-Chasid would not write it down lest he be suspected of being a believer of the word of R. Shlomo” (אבל ר’ יהודה החסיד לא רצה לכתוב פן יחשדוהו שהוא מאמין בדברי ר’ שלמה).

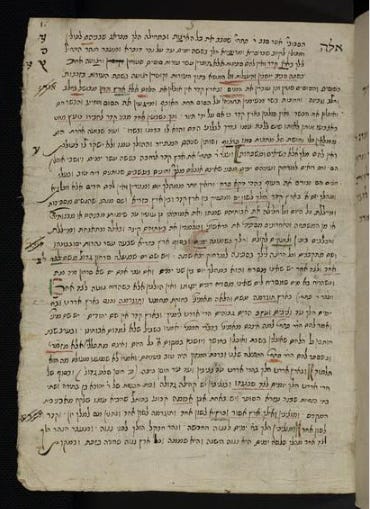

As such, the version that we possess of R. Petachia’s travels, known by the title Sivuv (Circuit), given to it by its first printer (Prague, 1595), is a heavily edited text. To make matters more complicated, the manuscript witnesses are relatively few and late, and present variant editions. Nevertheless, the Sivuv is substantial and chock-full of historical and geographical details that we are hard-pressed to find elsewhere. It remains a treasure of Jewish travel literature, particularly to the Land of Israel.

Reports on the Jewish Communities of the East

R. Petachia must have recorded a large amount of material about Jewish Babylonia (Iraq), especially Jewish society in Baghdad, or at any rate Yehuda he-Chasid chose to emphasize this material. The institutions of the exilarch and of the yeshivot (academies) continued to function in Baghdad, despite the reduction of their scope of influence.

A characteristic aspect of Petachia’s narrative may be seen in his description of Yechezkel (Ezekiel)’s grave:

ור' פתחיה הלך על קבר יחזקאל והביא בידו זהב וגרעינין של זהב ונפלי מידו הגרעינין ואמר אדני יחזקאל לכבודך באתי ונפלי ממני הגרעינין ינאבדו בכל מקים שהם יהיו שלך. והיה נראה בעיניי רחיק ממני כמי כוכב היה סבר שמא אבן טיבה, לא ראה יהלך ומצא הגרעינין ונתנם על קבר יחזקאל. וכל ישמעאל שהולך לאותו מקום ששם מחמט הילך דרך קבר יחזקאל וניתן מתנה ינדבה ליחזקאל ונידר ומתפלל יאמר אדוניני יחזקאל אם אשוב אתן לך כך יכך, ודרך מדבר הולכים שם בארבעים יום ימי שיידע בדרך הולך בעשרה ימים מקבר יחזקאל עד נהר סמבטיון, וכל מי שרוצה ללכת בארין מרחקים מפקיד ביסי אי שים חפץ ליחזקאל יאימר אדיניני יחזקאל שמיר לי חפץ זה עד שאשוב יאל תניח לקחתי שום אדם אלא יורשיי וכמה כיסים של ממין מונחים שם שנרקבו לפי שכמה שנים מונחים שם, והיו שם ספרים ורצה להוציא אחד מן הרקים אחד מן הספרים ילא היה יכיל כי אחזתי יסורין יעיורין, לכן מתפארים כל העולם מיחזקאל. וכל מי שלא ראה בניין פלטין שלי הגדול על קברי לא ראה בניין יפה מעולם, ובפנים מחופה זהב יעל הקבר סיד גבוה כאדם ועל הסיד סביב ועל גביו בניין של ארז מוזהב יעין לא ראה דוגמתי, ויש לו חלונים שאדם מכנים ראשי ומתפלל ולמעלה עשוי כיפה גדולה של זהב ומעילי יפי' מקיפי' מבפני' וכלי זכוכית בתוכו יפה מאד. ושלשי נירות של שמן זית דולקי' שם יומם ולילה וקונין מן המתנות שניתנין שם השמן זית ומדליקין עליו כשלשים נירית. ויש ממונים על המתנות שנותנים על קברו כמאתים פרנסים זה ממונה אחר זה, ימאותי ממון שניתנין על קברי מתקנים בית הכנסת שצריך תקון ומשיאין בין יתומים ויתומית ומפרנסין התלמידים שאין להם במה להתפרנס.

Rabbi Petachia went to the grave of Ezekiel, and took with him gold, and gold grains, and the grains fell from his hands, and he said: my Lord Ezekiel, for thy honour have I come, and now the grains have dropped from my hands and are lost. Wherever they may be they are thine. And he saw what in the distance looked like a star. He thought it might be a precious stone. He then went there in that direction, and found the grains, and placed them on the tomb of Ezekiel. Every Ishmaelite [Muslim] that goes in pilgrimage to the tomb of Mahomet [Muhammad] takes his way past the tomb of Ezekiel and makes some present or free-will offering to Ezekiel, making a bow and praying; our Lord Ezekiel, if I return I will give thee such and such a thing. The journey by way of the desert takes forty days from the tomb of Ezekiel to the Sambation. Whoever wishes to go to a distant land deposits his purse, or his valuables, with Ezekiel, saying: our Lord Ezekiel, take charge of this valuable for me until I return, and let nobody take it but the rightful heir. And many purses with money lie there rotting because they have lain there many years. There were at one time books there, and a worthless person wished to carry away one of the books, but could not, for pain and blindness seized him; therefore, everyone fears Ezekiel. Whoever has not seen the beautiful large structure over his grave has never seen a fine building. It is overlaid inside with gold. Over the grave of lime, is a structure of cedar wood, which is gilded; the eye never saw the like. There are windows in it high as a man, and round the lime, through which people pass their heads and pray. At the top is a large cupola of gold, and beautiful carpets cover the inside. There are also in it beautiful glass vases, and thirty lamps fed with olive oil burn there day and night. They are supplied with oil paid for out of the gifts deposited for the lighting of the thirty lamps. There are about two hundred overseers appointed for the administration of the gifts deposited on this grave, who discharge their office one after the other. From the money deposited on this grave, the synagogue requiring repair is repaired, orphans receive marriage portions, and destitute disciples are supported.

Ed. Grünhut, pp. 14-16; trans. Adler, pp. 75-76.

Notice the multicultural nature of visits to Yechezkel’s tomb, the grandeur of its upkeep, and the many folk rituals surrounding it. Here, not uncharacteristically, Petachia combines fantastical elements, such as the mythical river known from rabbinic literature as the Sambatyon, with factual descriptions of pilgrimage.

Petachia’s Experiences in Eretz Yisrael

R. Petachia speaks of Jerusalem as being under Christian rule, which indicates that he was there before 1187, when Salah al-Din (Saladin) captured it and reestablished Muslim rule. This means that he was in the Land of Israel only several years, perhaps up to a decade or so, later than R. Binyamin of Tudela. However, we already see in Petachia’s descriptions some changed, sometimes much-changed, circumstances. Whereas Binyamin found in Jerusalem a relatively robust Jewish community, Petachia reports, “The only Jew there is Rabbi Abraham, the dyer, and he pays a heavy tax to the king to be permitted to remain there.” (והלך לירושלים ואין שם אלא ר’ אברהם הצבע, והוש נותן מס רבה למלך שמניחו שם). In Binyamin’s telling, numerous Jerusalemite Jews worked as dyers, and paid for the exclusive right to this profession collectively to the king.

The small size of Eretz Yisrael is attested by Petachia: “The circuit of the land of Israel may be made in about three days” (ואמר ר’ פתחיה שכל ארץ ישראל כמהלך ג’ ימים). He demonstrates both a deep curiosity to confirm the sites mentioned in Tanach as well as a willingness to admit that they are no longer attested:

וראה ים המלח וסדום ועמורה, ואין בו עשב. ונציב מלח אמר שלא ראה ואינו בעולם. וגם האבנים שהעמיד יהושע לא ראה.

The rabbi [Petachia] saw the Salt Sea of Sodom and Gomorrah. There is no herb there. As to the pillar of salt, he said that he did not see it and that it no longer existed. Nor did he see the stones which Joshua erected.

Ed. Yaari, p. 53; trans. E. N. Adler, Jewish Travellers in the Middle Ages, p. 89

Petachia gives a similar description of access to the Cave of the Patriarchs (Maarat ha-Machpela) to that of Binyamin of Tudela, with some differences. He too recounts that the keeper of the Cave, a Christian, could be paid off—with gold, so not an insubstantial bribe—to take the visitor inside. He mentions that there are fifteen steps between the outer and inner cave, and the thick iron bars—“the like no man can make by earthly means but with heavenly help only” (ואין אדם יכול לעשות כזה אם לא מלאכות שמים)—covering the entrance to the innermost cave. R. Petachia, our narrator says, was warned by the Jews of Akko (Acre) that the Christians were mistaken about the location of the graves of the Avot (patriarchs). He finds them beyond the otherworldly iron gate, where an unforgiving wind blows between the bars. There, R. Petachia prays.

Reads and Resources

The Sivuv of R. Petachia can be read in this (good) 1905 edition by Lazar Grünhut and also in excerpted form in Avraham Yaari’s indispensable anthology, מסעות ארץ ישראל (Tel Aviv, 1946), pp. 48-54. A substantial, though partial, English translation is available in Elkan Nathan Adler’s Jewish Travellers in the Middle Ages, which is an older book that includes an account, of one Ibn Chelo, that has been proven to a forgery, but is otherwise serviceable. (Its base text is Yaari.)

Joshua Prawer’s book The History of the Jews of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (Oxford, 1988) is the English version of the Hebrew mentioned above in the text. It includes attention to R. Petachia’s account as well as much else gleaned from travel literature about the period.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective. If you’d prefer to make a one-time donation in any amount, you can do that easily through my page at Ko-fi. Thank you so much.

In the Hebrew article, “תיאורי מסע עבריים בארץ ישראל בתקופה הצלבנית” Cathedra: For the History of Eretz Israel and Its Yishuv / קתדרה: לתולדות ארץ ישראל ויישובה, no. 41, 1986, pp. 65–90; reprinted in the book תולדות היהודים בממלכת הצלבנים (יד בן צבי, 2000) as chapter seven.

What an insightful essay that sheds light on the little-known travels of the illustrious Rabbi Petachia of Regensburg (Whom I'm ashamed to say I knew nothing about). A brilliant piece!