R. Eliyahu of Ferrara's Journey to Jerusalem

🗺️ An Italian rabbi who became a pillar of the premodern Jewish community in Jerusalem penned a succinct and fascinating letter about the reality of aliyah in the fifteenth century.

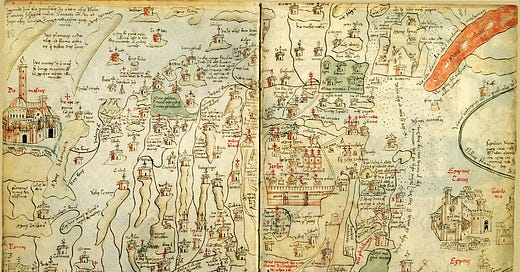

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. Last week, we took a look at a masterful halachic work centered on laws pertaining to the Land of Israel written by the careful geographer R. Estori ha-Parchi, who made aliyah from Provence. That book, Kaftor va-Ferach, remains a work of great importance both for halacha and for our knowledge of medieval Eretz Yisrael. Today, we shift into a much slighter document, but one with many fascinations of its own. A snapshot of aliyah from one otherwise unknown R. Eliyahu, this short letter—preserved in a single manuscript—allows us a glimpse into Eretz Yisrael in the mid-fifteenth century, a bit over a hundred years after Estori. It shows us a Jewish community struggling but persisting in its attempts to flourish in Jerusalem.

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here (and an archive of all audio editions here.)

In this issue:

In July of 1435, R. Eliyahu sat down in Jerusalem to write a letter to his children remaining near La Massa, a town in the Ferrara region of northern Italy. Concerned that his previous letters had failed to arrive at their destination—perhaps for lack of replies—he explained that he would repeat the outline of what had befallen him on his journey to the Land of Israel and since arriving there. The letter that remains and has come down to us is but one folio page in its entirety: that is, the front and back of a single page. But in this span of text, there is a richness of detail that allows us a window through which to peer at conditions on the ground. Because of its relatively diminutive size, below we’ll go through the entire letter so you can get a well-rounded glimpse at the source.

Of Journeys and Letters

Almost all that we know about R. Eliyahu of Ferrara, we know from his one letter that survives. (He’s not to be confused with the similarly-named R. Eliyahu of Pesaro, who set out for the Land of Israel in the mid-sixteenth century, but was stymied by an outbreak of plague and whose letters importantly describe conditions along the way.) Our R. Eliyahu does not give us the reason for his aliyah, though, as we’ll see, he made it with his at least two of his sons and one grandchild. An interesting feature of the letter is that it preserves the writing on the outside of the letter, where a seal would have generally been placed. This was the public-facing “address” of the letter, intended for the messenger (shaliach) and the addresees. We occasionally see such addresses preserved in medieval Hebrew letters, and they often contain information that helps us better understand how information was conveyed in premodern conditions.

Here—to begin with the ending—R. Eliyahu intones blessings upon his friends, Yisrael Chaim and Yosef Baruch, to whom the messenger is to deliver the letter. He then requests of “my lords and brethren of the Holy Community of Ferrara” that the letter be passed along to his sons “wherever they may be.” This tells us that the messenger was enroute to Ferrara, from where the letter could be further dispatched as needed. R. Eliyahu had been gone from Italy sufficiently long to be unsure about the exact whereabouts of his sons. Such an “address” would also serve as a means of authenticating the document and naming its intended recipient(s). In some cases, the recipient or kahal (community) to which a letter was sent had real halachic weight, marking the letter, especially one of sensitive contents, as private or public and ensuring it was opened by the authorized recipient.

Another way in which R. Eliyahu’s letter reveals to us the realities of undertaking long journeys in premodernity is in his opening remarks about the travails he suffered along the way. R. Eliyahu sailed from south Italy to Egypt, a common route for Italians in the fifteenth century. Although we think of this as a relatively short sea voyage today, it could be a treacherous one in the fifteenth century, both in terms of personal security and in terms of hygiene conditions. Indeed, R. Eliyahu opens with sorrow at the ill health he and his sons and grandson suffered as an apparent result of their travel, which ultimately claimed the lives of his loved ones. First his brilliant grandson, Yaakov,—“one most near and dear, the desire of my eyes, the joy of my heart”—succumbed to illness. Next, R. Eliyahu’s son Menachem, “the child of my old age,” passed away, after which he writes: “My soul rejects all consolation for the death of this beloved son…grief is added to grief.” A few days later, another beloved son, Yitzchak, died as well, and R. Eliyahu himself fell gravely ill. This is in addition to an outbreak of plague he endured in Jerusalem somewhat later, where some ninety members of the community perished—still short of the five hundred who succumbed in Damascus, which also shows the relative sizes of the two cities.

The Jewish Community of Jerusalem in the Mid-Fifteenth Century

R. Eliyahu reports that he then arrived in Jerusalem, on the forty-first day of the Sefirah period (between the holidays of Passover and Shavuot) in the year 1434. He was still recovering from serious illness when the communal leaders came to ask him to begin teaching in the community. He was first tasked with teaching “chapters of the Rambam [Maimonides]” (הפרק במיימוני), evidently the Mishneh Torah, “according to their practice.” The community was sufficiently impressed that they requested a far larger teaching load:

ומאז שתו עיניהם עלי והעמיסו עלי משא ככך להגיד שלש פעמים ביום: הפרק בבית הכנסת, והלכה עם תוספות המדרש, והלכה עם פי’ רש”י עוד בבית הכנסת לפנות ערב, מלבד טורח הדינים פה במקומי וההוראות בער מצרים ובאלכסנדריא ובדמשק ומקומות אחרים הקרובים והרחוקים, לא יאמינו כי יסופר.

From then their eyes drank me in and they heaped upon me the burden of teaching three times a day: the chapter [of Rambam] in the synagogue, and halacha with Tosafot in the Beit Midrash [study hall], and also halacha with the commentary of Rashi in the synagogue in the late afternoons, and this is in addition to the labor of responding to court cases here in my place as well as in Egypt and Alexandria and Damascus and many other near and far places, you would not believe the telling of it.

Letter of R. Eliyahu of Ferrara (“Ahavat Tziyon”), my translation

Here we see an eclectic curriculum encompassing Sefardi and Ashkenazi elements, with halacha being taught both to students in the Beit Midrash and to laypeople in the synagogue. It seems the R. Eliyahu’s expertise in matters of law was highly regarded and needed, such that he served as dayan (rabbinical court judge) and authority for the entire region.

R. Eliyahu also mentions that his modest salary nevertheless goes far, “because provisions here are plentiful and abundant and cheaper to buy (thank G-d) than in any other place where I lived in the West.” In other words, the local economy was weak in comparison to Italy’s but there was no lack of basic goods. He details common professions: people worked as shopkeepers, especially sellers of silk, carpenters, goldsmiths, and pharmacists, although he notes that the pharmacists are resellers rather than compounders. From this and other comments in the letter, it appears that R. Eliyahu may have had medical training.

Lost Tribes

The remaining third of R. Eliyahu’s letter turns to reports from the east, including the whereabouts of the ten lost tribes of Israel. We have seen interest in this subject several times among travelers’ accounts, and today we’ll take the opportunity to explore it in more depth. First, he relays reports he’s heard about Ethiopian Jewry from a young Ethiopian Jew with whom he conversed:

הם אדונים לעצמם ואינם ברשות אחרים, ובסביבותיכם אומה גדולה נקראים חבש (אביסיניא), ומתנצרים בשתי וערב על פניהם תמיד נלחמים הם בהם, [ועם העברים נלחמים] רק לעתים. והעברים ההם יש להם לשון בפני עצמם. לא עברי ולא ישמעאלי, ויש להם התורה ופירוש עליה על פה, ואין להם לא התלמוד ולא הפוסקים שלנו וחקרתי ממנו כי בכמה מצות בקצתן נוטים לדעתנו ובקצתן נוטים לדעת הקראים ויש להם מגילת אסתר [ופורים] אבל לא חנוכה ורחוקים ממנו מהלך ששה חדשים, ובארצם נמצא נהר גוזן

[They] are their own masters, and owe no dependence to anyone. They dwell among a great nation called Habesh [חבש - Abyssinia, today’s Ethiopia], [who] make a show of [their] Christianity…they [the Jews] are constantly at war with them [the Christian Ethiopians] and only now and again with other Jews. These Hebrews have a language of their own. It is neither Hebrew nor Ishmaelite [Arabic]. They possess the Torah and a traditional oral commentary upon it. They have neither our Talmud nor our codes. I have obtained information from this young Jew about several of their precepts. In some they follow our doctrine; in others they conform to the opinions of the Karaites. They are in possession of the Book of Esther [and celebrate Purim], but they do not have Chanukah. They are a six months’ journey distant from us, and the river Gozan1 flows through their regions.

Letter of R. Eliyahu of Ferrara, (“Ahavat Tziyon”), trans. E. N. Adler, with slight modifications

After description of the communities of “new” and “old” Babylonia, R. Eliyahu turns to reports from farther east: India. He claims that he has heard of a king who rules over the Jews of India alone, which may be a reference to a Prester John-like figure, or perhaps to tales of a local Jewish ruler on the Malaber coast that circulated in the later middle ages. R. Eliyahu reports that the rest of the country consists of vegetarians “who kill no living creature for food”—a overly broad heuristic, to be sure, but one that has some basis in reality. He also characterizes Indian religion through the lens of Talmudic paradigms: “Their adoration is given principally to the sun, moon, and the stars.”

R. Eliyahu’s descriptions of others of the ten tribes of Israel, lost in the exile of the ancient northern kingdom of Israel, are, like others of his reports of reports, based heavily upon the testament of Eldad ha-Dani. Eldad was a ninth-century figure who appeared in Qayrawan (Kairouan) in north African, claiming to be of the lost tribe of Dan (hence, ha-Dani, “the Danite”). He presented a copious amount of information about Dan and several other tribes, some of it clearly mythical. However, Eldad also presented alternative halachot (Jewish laws), especially pertaining to kosher slaughter, that were widely considered authentic by Rishonim (medieval Torah scholars) and seem to invoke a genuinely divergent tradition. (Eldad didn’t travel to the Land of Israel, so alas, I had to leave him out of the current series.)

R. Eliyahu, like Eldad, talks about the Sambation River, mentioned in rabbinic literature, which is described differently in different sources but in all behaves differently on Shabbat. He claims that the tribe of Moshe (i.e., the Levites) live on one side of the Sambation with the tribe of Menashe, while the tribes of Dan, Naftali, Gad, and Asher live on the other side. R. Eliyahu reports that Issachar is an isolated tribe dwelling in its own land without contact with the others; this seems to be somewhere in Persia, since they speak Persian alongside Hebrew and Arabic, according to R. Eliyahu, and “dwell among fire worshippers,” perhaps Zoroastrians. The tribe of Shimon lives “to the extreme south,” while Zevulun and Reuven are in Babylonia, on either side of the Euphrates River, with Efraim to the south. The former two tribes, in R. Eliyahu’s telling, possess the Mishnah and the Talmud.

In closing, R. Eliyahu mentions that he’s holding off on describing graves of holy figures because he intends to visit them soon, after which he’ll be able to record his own, direct impressions of them. Like so many before him, praying at the gravesites of revered Jewish people was a stirring prospect for spiritual edification. Experiencing the actual siting of holiness in the Land was real and important to R. Eliyahu, as it was for so many who made aliyah in premodernity.

Reads & Resources

You can read the Hebrew account of R. Eliyahu of Ferrara in two of the anthologies I’ve mentioned before, J. D. Eisenstein’s אוצר מסעות, pp. 83-43, and Avraham Yaari’s אגרות ארץ ישראל, pp. 86-89. The full English is in Adler’s Jewish Travellers in the Middle Ages.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective. If you’d prefer to make a one-time donation in any amount, you can do that easily through my page at Ko-fi. Thank you so much.

Adler suggests that this refers to the Nile, but the Gozan River is usually identified with the Sambation, on which, see below.