Rishonim, Autographed and Illuminated

📜 For the conclusion of the Famous Hebrew Manuscript series, a look at important or beautiful manuscripts of Rashi, Rambam, and Tur.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. Today we’re spending time with a few rare manuscripts from the period of the Rishonim that characterize the type of information by which manuscript work enriches our knowledge of our core texts, as well as several beautifully decorated works that emphasize the value placed on medieval texts.

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here (and an archive of all audio editions here.)

In this issue:

On the one hand, when it comes to the works of the Rishonim, the manuscript attestation for their works can be complex; for example, a work like Ibn Ezra’s Torah Commentary is preserved in numerous piecemeal manuscripts in up to three versions. On the other hand, there are generally few early manuscripts, and even fewer autograph copies, meaning manuscripts handwritten by the text’s author. This makes each early textual witness exceedingly precious and autograph copies, particularly ones with corrections or additions, critical for research and understanding. Below, we’ll look at an important examples of an early witness and autograph copies.

The Leipzig Rashi

Rashi’s commentaries, on both Tanach and Talmud, were epoch-making works, each playing, however, a very different role in Torah learning. In particular, the Talmud commentary “opened” the challenging text to generations of students in Ashkenaz with its clear explanations of key concepts, difficult words, and the background of the dialectical argument. The Torah commentary, meanwhile, had two disparate effects: first, it brought into wider circulation chosen passages of Midrash that serve as explanations of the text of Tanach, and second, it instigated a peshat revolution (of contextual reading of Tanach) in northern France in the 1100s and 1200s.

Both of Rashi’s commentaries were, in a way, the work of many hands; the Talmud Commentary was likely based upon students’ notes from Rashi’s ten years of study in the Rhineland Valley, while some thirty or more percent (in Dr. Avraham Grossman’s estimation) of the Tanach Commentary is comprised of citations from Midrash. But in addition to the use of Midrash in the Tanach Commentary, manuscript research demonstrates that a fairly significant percentage of Rashi’s commentary as we have it today incorporates glosses made by his students. In part, this stems from the approach to text in Ashkenaz, which was seen to have more porous boundaries than in Sefarad. Ashkenazi scribes felt comparatively more at liberty to rearrange units of text and to emend them as a means of adding knowledge.

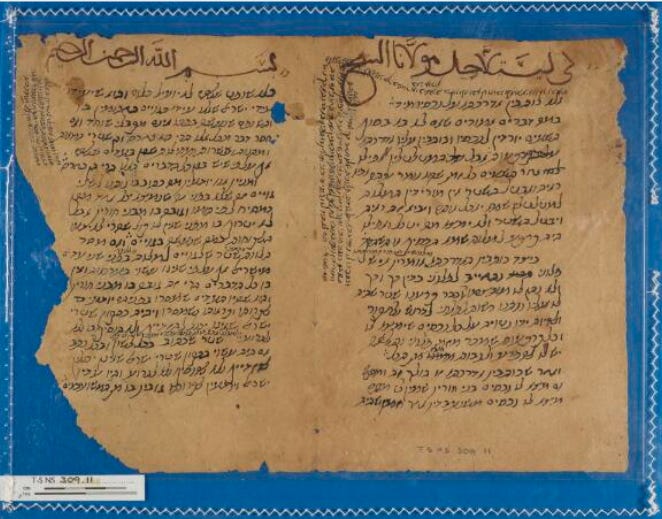

In the case of the “Leipzig Rashi” (Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig Ms. BH 1), which dates from the 13th century and includes Chumash and Megillot (the end is missing), the text is significant in two key ways. First, its scribe, Machir ben Karshavya (מכיר בן קרשביא), states that he is copying from a manuscript prepared by Rashi’s leading student and personal secretary, R. Shemaya. Secondly, Machir, against the Ashkenazi trend, copied emendations by R. Shemaya separately from the main text of Rashi’s commentary, as can be seen visually in the first image above. These permit us to see that many of R. Shemaya’s emendations are copies of Rashi’s own corrections. They also permit a comparison with later manuscripts and early printed versions that evidence the interpolation of emendations into Rashi’s commentary. This makes the standard Rashi on the Torah that we have before us today a composite work, to some extent. Leipzig 1 thus both complicates the notion of an original text and gives us a closer look at what Rashi’s own words on the page might have been.

Rambam Autographs

We possess, for the medieval period, an unusually large (relatively speaking) and important set of autograph manuscripts by Rambam. These make it eminently possible to recognize his rather blocky handwriting. Of particular significance are manuscripts attesting to the text of Mishneh Torah, Rambam’s groundbreaking law code. These include a manuscript (Bodleian Library, Oxford, Ms. Hunt. 80) of the first two, theologically-oriented books of Mishneh Torah, Sefer ha-Madda and Sefer ha-Ahava, authorized by Rambam thus (on fol. 165r): “Corrected from my own copy, I, Moshe the son of Rabbi Maimon of blessed memory.”

In addition to this authorized copy of Mishneh Torah, the Cairo geniza, a treasure-trove of texts from the Fustat (Old Cairo) Ben Ezra synagogue, most dating from the 10th to the 13th centuries, has yielded a number of additional autograph responsa by Rambam. Among them are additional fragments of Mishneh Torah with corrections (Cambridge University Library T-S NS 309.11, shown above; Bodl. Ms. Heb. d. 32/G.1 and G. 2, 32.47-50, 53, 55-56; University of Manchester Library Mss. B 5756, A 281, and B 6210; JTS Ms. ENA 2632.24).

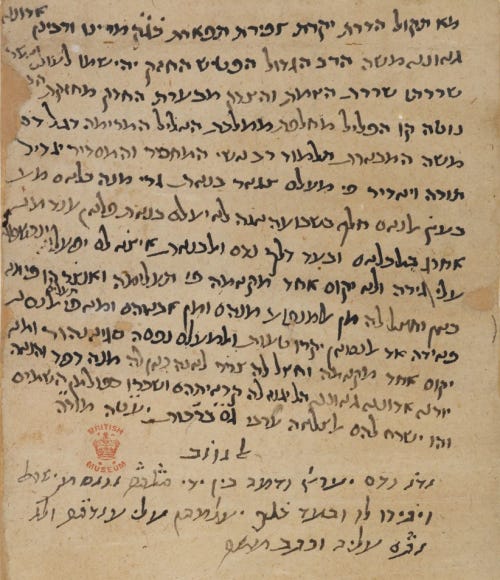

Also found in the Cairo geniza: a fragment (T-S 10Ka4.1) of an autograph copy of Moreh ha-Nevuchim (“The Guide of the Perplexed”). Clearly visible in the image above is a line crossed out by Rambam.

There are also a number of important responsa, including a signed teshuva (British Library Ms. Or. 5519B) which is simply concluded with “thus wrote Moshe.” Others are unsigned but authenticated by careful handwriting analysis. One (T-S 12.192) deals with Jewish immigrants to Egypt (a matter close to the heart of Rambam, an immigrant to Egypt himself); another (T-S 12.832) with inheritance; and a third is addressed to a judge (T-S AS 149.89; see also T-S AS 111.164). T-S 16.290 is a particularly interesting anonymous query asking for philosophical instruction and a correspondingly appropriate dietary regiment. (Rambam recommends almonds, raisins, and date honey. Philosophy is apparently aided by sweets.) It may well include a partial, inadvertantly-inked fingerprint of Rambam’s: scroll down here to see.

Rambam, Illuminated

There are three standout illuminated editions of Rambam’s works, two of Mishneh Torah and one of which is likely a miscellany of his philosophical works. The earliest of these is the miscellany, also known as the “Vienna Maimonides,” since it is owned by Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Austrian National Library, Cod. Hebr. 197). This manuscript includes the theological Introduction to Perek Chelek from Rambam’s Mishnah Commentary, which includes the Thirteen Principles of faith; Shemona Perakim, Rambam’s introduction to Pirkei Avot; and then Rambam’s Commentary on Pirkei Avot, all in R. Shmuel Ibn Tibbon’s Hebrew translations.

The Vienna Maimonides was created in 1283 by the master Italian illuminator-scribe Avraham ben Yom Tov ha-Kohen, who is known to have produced a number of magnificent manuscripts for his patron, Shabbetai ben Matityahu. (One of these is an illuminated Bible mentioned in last week’s newsletter.) It has been suggested that two other, similarly decorated manuscripts, one of Moreh ha-Nevuchim (British Library Ms. Harley 7586a) and another of various philosophical works (“the Casantense Miscellany,” Biblioteca Casanatense, Rome, Ms. 2916), were once part of this manuscript as well. These are not explicitly signed. However, the latter includes dotted letters spelling out mechokek (“engraver” - מחוקק), which Dr. Malachi Beit-Arié, the eminent Hebrew codicologist, has identified as a professional moniker of Avraham ben Yom-Tov ha-Kohen (mechokek also equals “Avraham” in gematria, Hebrew letter-math). And it records works found in the Casantense Miscellany.

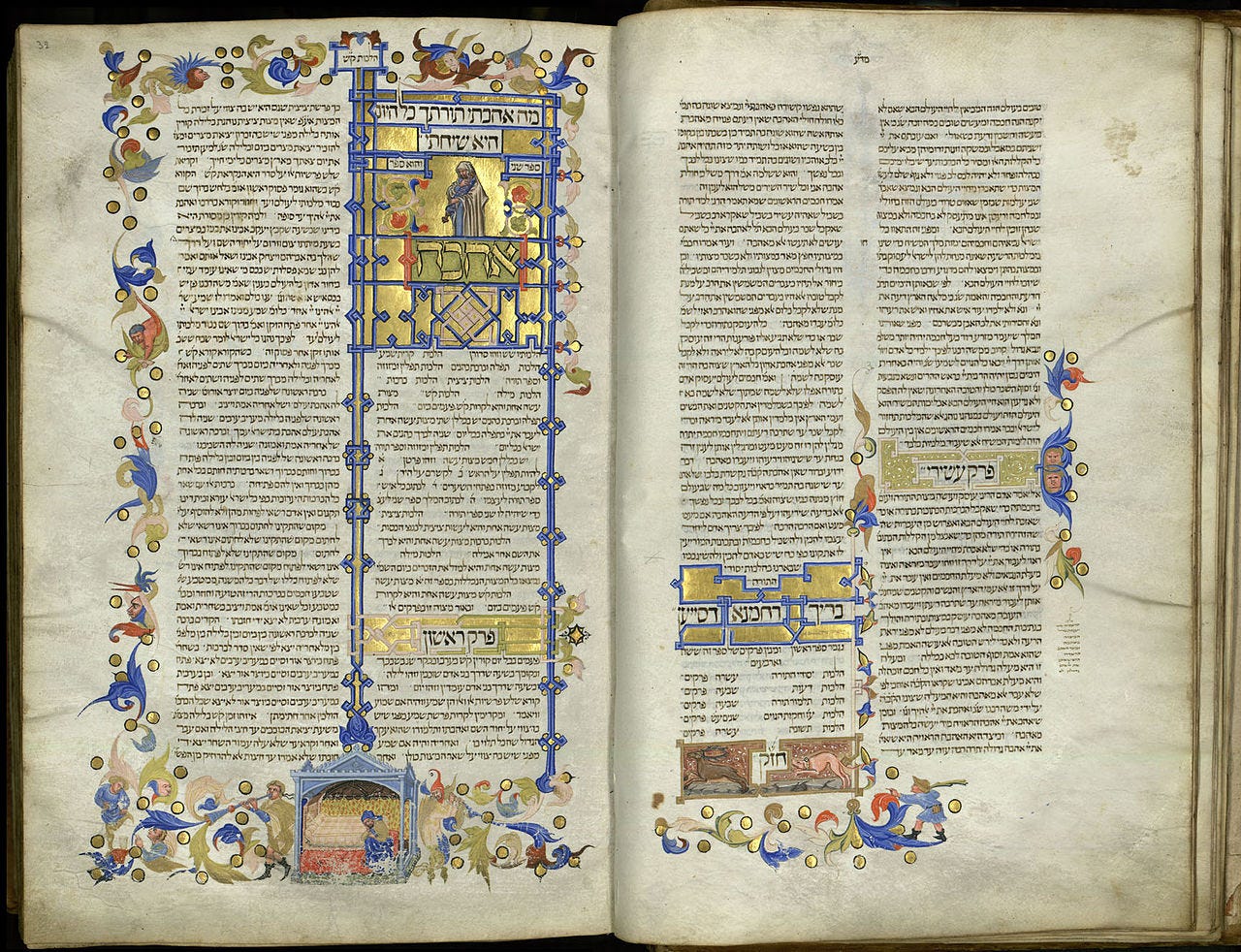

Created in Spain c. 1350, the illuminated Mishneh Torah (National Library of Israel, Jerusalem Ms. Heb. 4°1193) was designed to be decorated by a master artist. The opening pages seem to have been illuminated by a Spanish artist, while most of the decorations seem to be those of an Italian Christian illuminator, Matteo di Ser Cambio (compare here and here) that were added later, c. 1400. Interestingly, areas were left blank where Rambam created diagrams for the artist to fill in in the section on the kelim (instruments) of the Beit ha-Mikdash in Hilchot Beit ha-Bechira, bearing the captions per Rambam’s text.

The “Lisbon Mishneh Torah” (vol 1: British Library Ms. Harley 5698; vol. 2: British Library Ms. Harley 5699), produced in Lisbon, Portugal in 1472, also presents an elaborately illuminated version of Rambam’s law code. Like the Spanish Mishneh Torah, it features decorated opening pages to the books of the code.

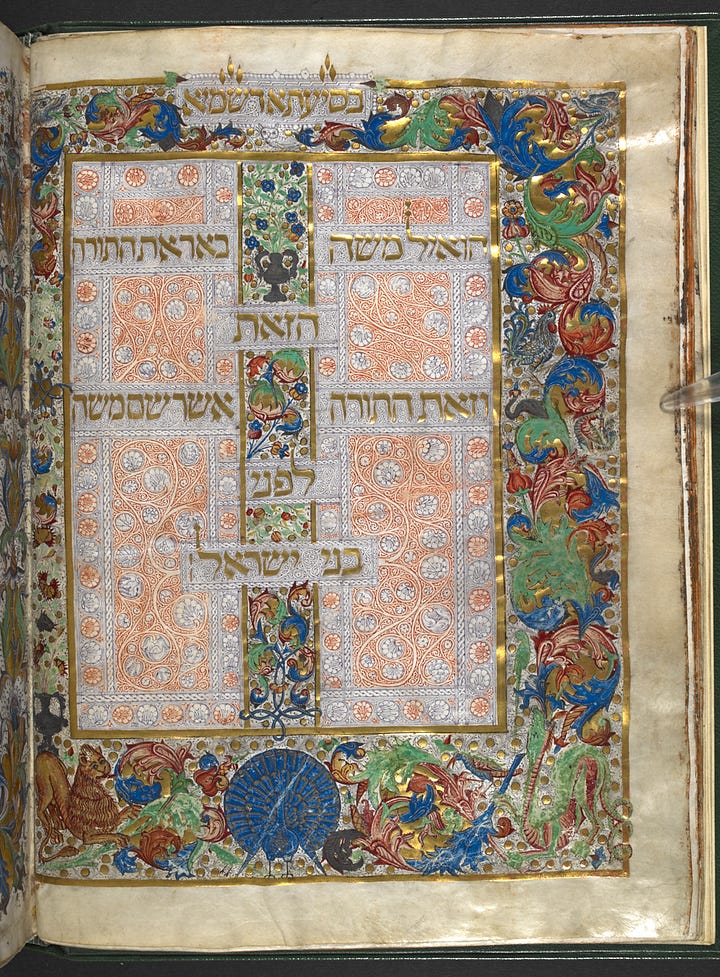

A Decorated Arbaa Turim

In 1435, only a century or so after its composition, R. Yaakov ben Asher (the Tur)’s world-changing law code, Arbaa Turim, received lavish illuminated treatment (Vatican Library Ms. Ross. 555; digitized here.) Produced in Mantua, it seems to follow the 15th-century Italian predilection for luxurious book productions for wealthy patrons. Here, it recognizes and dignifies a relatively recent work with an eminent position in the canon of Jewish law. The manuscript also includes glosses of difficult words preceding the chapters, showing its utility to the student, and indeed it shows many signs of wear.

Reads & Resources

A critical edition of Rashi on the Torah based on Leipzig 1 is available freely online via Al-HaTorah. See here for more details about the project. Sefaria does not have the manuscript view of Leipzig as far as I could tell.

For an example of how Leipzig 1 can affect our understanding of Rashi, see “What if the Maharal of Prague Had Access to Leipzig 1 and Other Manuscripts?” by Eli Genauer on the Seforim Blog.

For an example of how the autographs can affect our understanding of Rambam, see “Oxford's Autograph of Maimonides' Mishneh Torah: Does G-d sleep?” on the Oxford Chabad site.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective.