Illuminated Hebrew Bibles

📜 From Spain to Germany to Yemen, Jews of the mid- to late Middle Ages began producing decorated Bibles, some with smaller ornamentation and others with detailed, gold-leafed miniatures.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. Around the same time we start seeing those beautiful illuminated haggadot being produced, we see, to a lesser but still exciting extent, the production of illuminated Hebrew Bibles. Today, we turn to these masterpieces, which come from all over the Jewish world.

In this issue:

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here (and an archive of all audio editions here.)

In our exploration of illuminated machzorim and haggadot over the past few weeks, we saw that most of the machzorim were from Ashkenaz and that haggadot came from both Ashkenaz and Sefarad, each with distinct characteristics but often sharing common influences. When it comes to illuminated Tanachim, we see, interestingly, examples from across the Jewish world. It was, perhaps, a common impulse to elevate such a holy text with artistic embellishment.

Early Illuminated Bibles: To the 13th Century

The earliest decorated volumes of Tanach are Karaite and date as early as the ninth century. They tend to feature carpet pages with geometrical motifs, so called because they resemble the design of an elaborate Central Asian carpet. (You can see an example of carpet page at the top of this newsletter, with micrography too, another classic feature of Jewish manuscript decoration.) We also have two 11th-century slightly decorated Bibles from Persia, which feature a few small, marginal decorative elements (British Library Ms. Or. 1467, fols. 43v–44r and British Library Ms. Or. 2363, fol. 73v; click on the links for the folio page numbers to see them opened to the decorated pages). The First Gaster Bible (British Library Ms. Or. 9879) dates from 10th-century Egypt (most likely) and features decorative elements in gold.

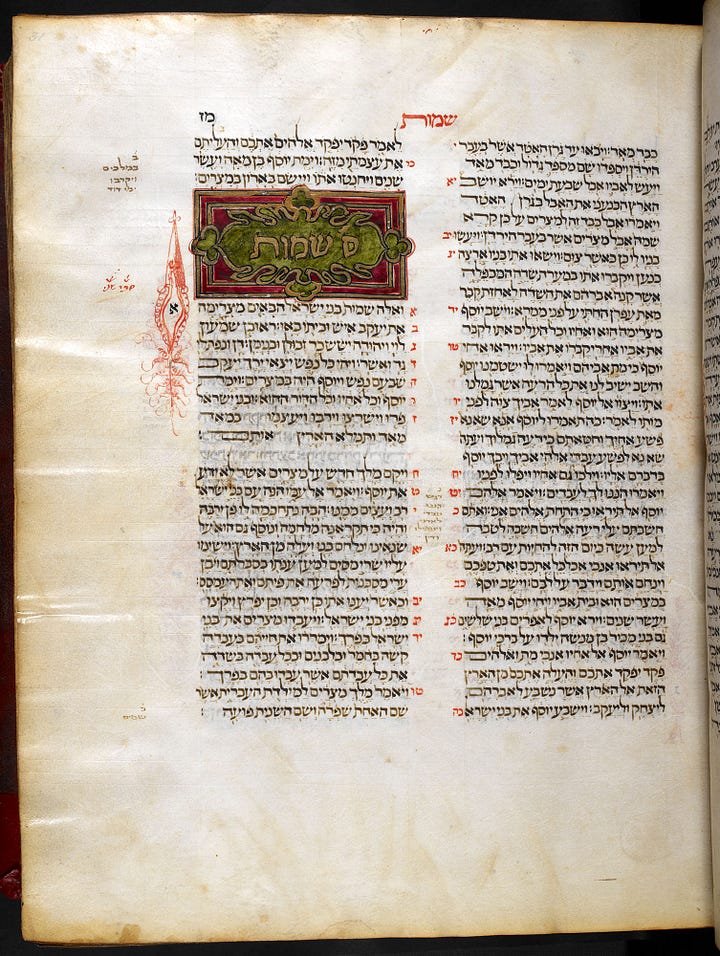

After that, we begin to see decorated Tanachim from Italy. In 1284/5, the master illuminator-scribe Avraham ben Yom Tov ha-Kohen created a delicately decorated Tanach (Emmanuel College Library, Cambridge, England Ms. I.I.5-7/1) for his patron, Shabbetai ben Matityahu, for whom he also produced several other known works, including the “Vienna Maimonides,” which bear similar decorations. The illuminations consist of frontispieces and “opening gates” for the books featuring decorative arches, and the text includes vowelization and cantillation marks and Masoretic notes. (The images do not allow reuse but see here for a beautiful example of the illumination style.) Avraham ha-Kohen also composed an opening poem for the manuscript and left an interesting note that mentions the slight differences between the text known in Rome and “the copies which came from Sefarad.”

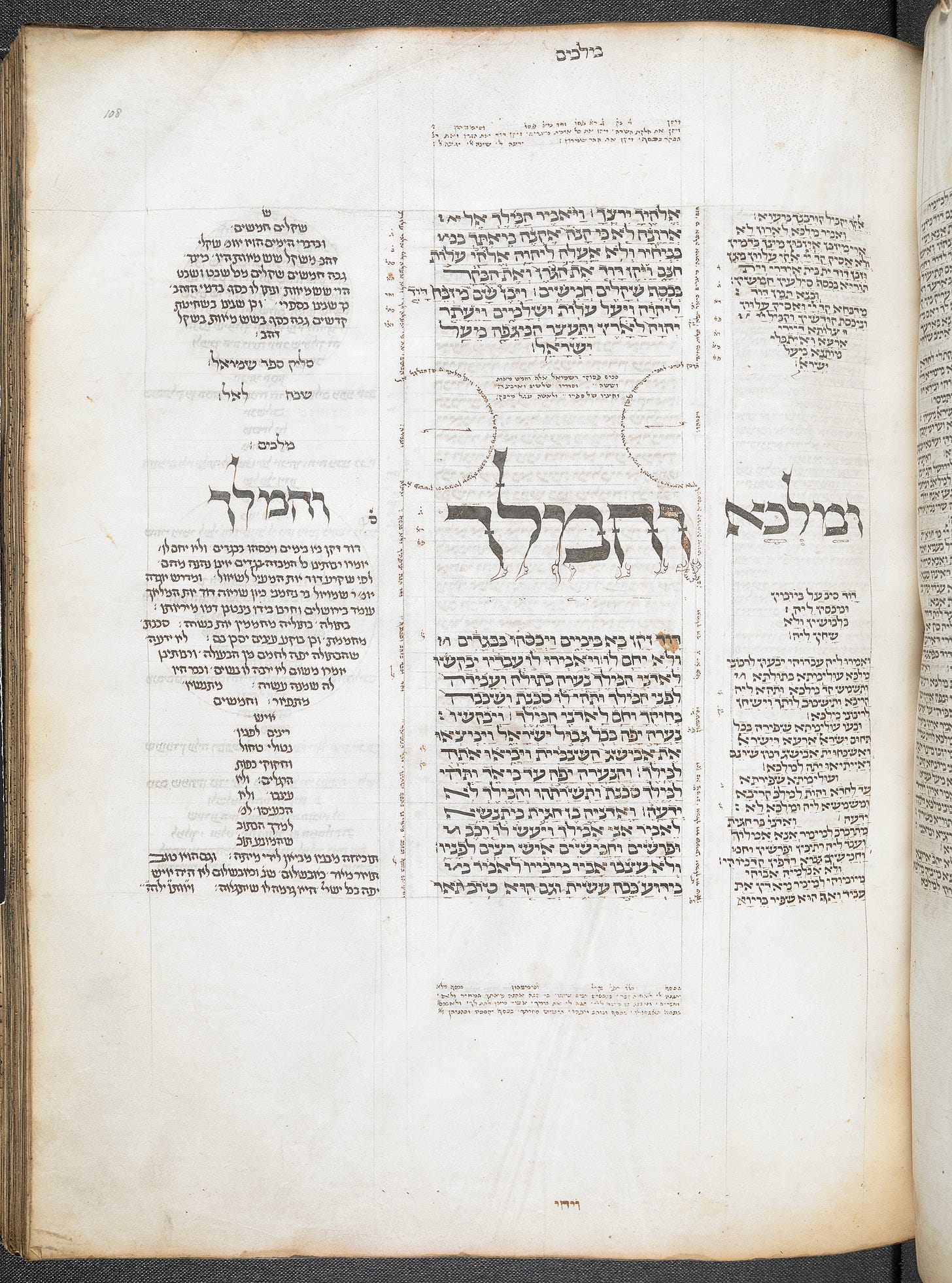

While not illuminated, an important 13th-century Ashkenazi precursor to the multi-commentary page layout that was established by early printers in early modernity is British Library Ms. Add. 26879. This manuscript of Neviim (the Prophets section of the Bible) includes Targum Yonatan, the canonical Aramaic translation of the Biblical text, but also, unusually, includes Rashi’s commentary. In addition, it uses decorative elements in the layout of the text. A fully illuminated 13th-century Bible from Ashkenaz is the Ambrosiana Bible (Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, Italy Ms. B. 30-32 Inf.), which we looked at earlier in exploring the Birds’ Head Haggada: it, too, features animal-headed humans.

Later Illuminated Bibles: 14th-15th Centuries

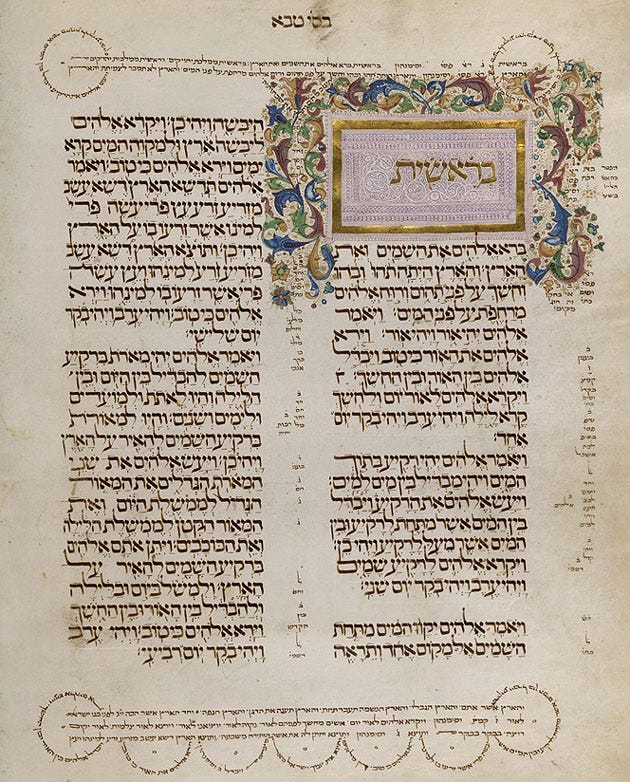

In the 1300s in Spain and Portugal, we begin to see the production of exquisitely illuminated manuscripts of the Tanach, including some with the complete 24 books (per the tradition enumeration). Dating from before 1326, Rylands Heb. Ms. 36, now at the University of Manchester in the UK, was created in Spain but features French or possibly Italian-influenced designs. On the decorative panel for the opening of Sefer Bereshit, we see a delicate floral pattern, fine gold-leafing, and centuries of wear.

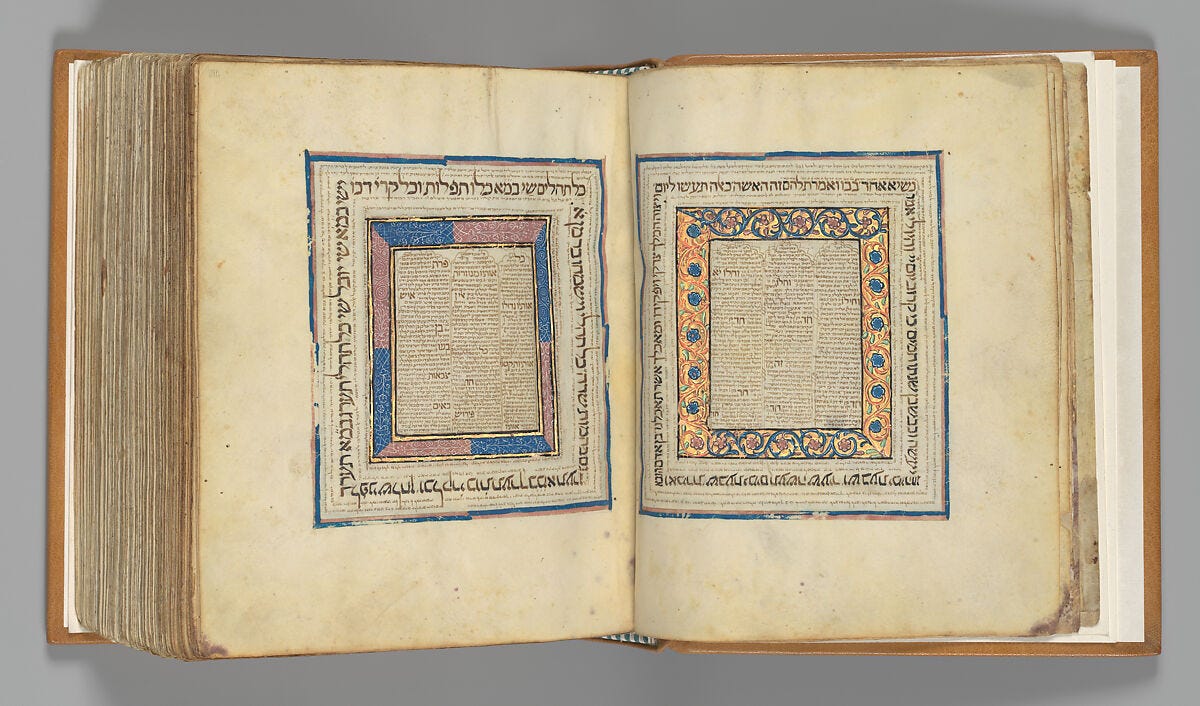

Produced before 1366 in Castile, the Metropolitan Musuem of Art’s Sefardi illuminated Bible (Cloisters 2018.59) features elaborate text layouts on select pages, stunningly delicate decorations, and fine gold-leafing. The volume is complete and features vowelization, cantilliantion marks, and Masora (critical apparatus). The motifs show the influence of both Christian and Islamic art.

Another beautiful Sefardi 14th-century Bible is the King’s Bible (British Library, Kings Ms. 1), produced in Catalunya (northeastern Spain) in 1384/5 by Yaakov ben Yosef Ripoll for Yitzchak ben Yehuda of Tulusa (possibly Tolosa or Toulouse). It’s so called because it eventually passed into the ownership of King George IV, who donated it to the British Library in 1823. In the image at top right, you can see similarity both to the Met’s Castilian Bible and the earlier carpet page technique. There are also ink and gold initial word panels and marginal embellishments in the text.

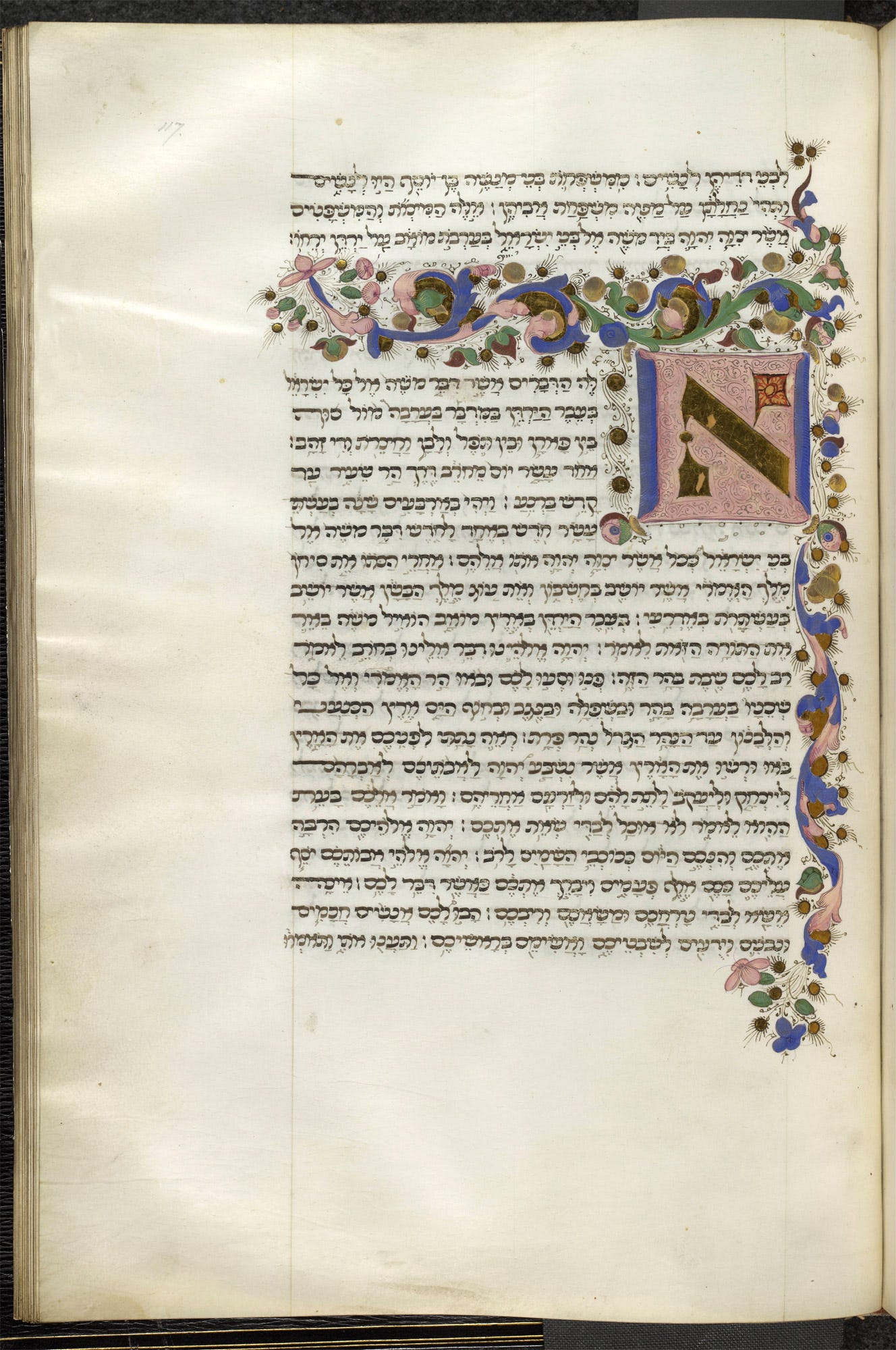

In Italy too in this period, we see the continued production of illuminated Bibles. The Duke of Sussex’s Bible (British Library Ms. Add. 15423), c. 1441–1467, is notable in that it features decorated initial letters as opposed to initial words, more commonly seen in Hebrew manuscripts. The scribe, Yitzchak ben Ovadia of Forli, known in the vernacular as Gaio di Servadio (active in Florence in the mid-15th century), used an Italian semi-cursive script that resembles the script often used in contemporary Latin manuscripts.

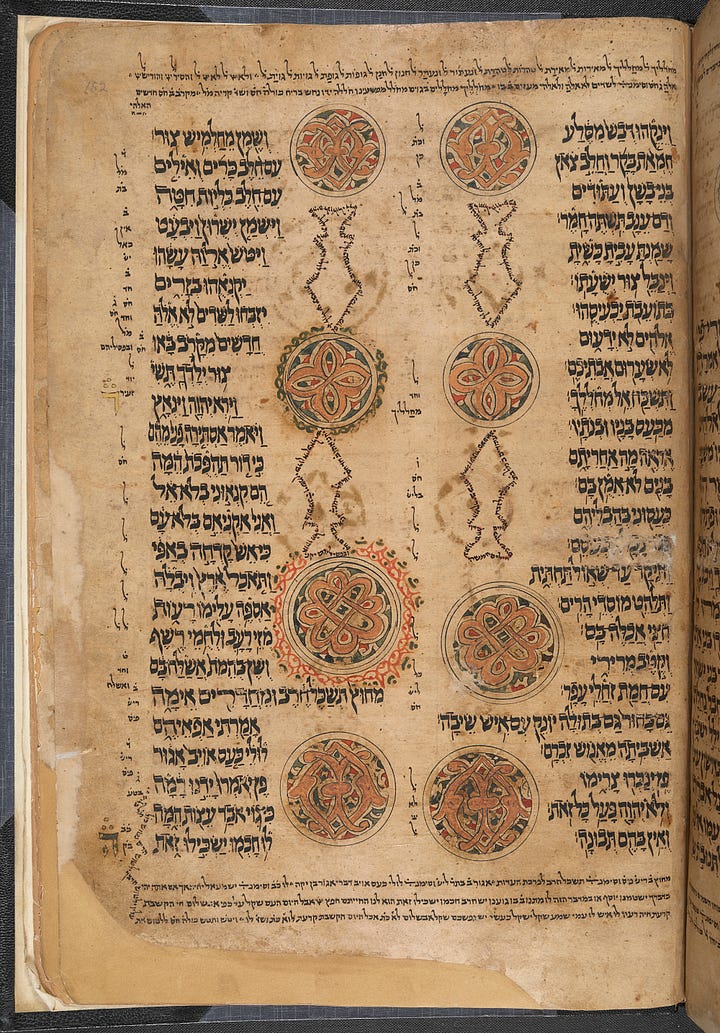

The Sanaa Pentateuch (British Library Ms. Or. 2348) is an example of an illuminated Torah from Yemen, produced in 1469. It employs micrography—miniature letters forming shapes of figures—and geometrical patterning to stunning effect. By comparison with other signed manuscripts, the scribe has been identified as Benaiah ben Saadia ben Zecharia ben Marga (d. 1490). It is thought that he was also the illuminator. The fish micrography seen on the pages above is characteristic of the manuscript.

Three Superstar Bibles

Three Tanach manuscripts spanning the years 1300-1500 reach, perhaps, an apex of decorative brilliance: the Cervera Bible, the Kennicot Bible, and Lisbon Bible. The oldest of the three is the Cervera (National Library of Portugal, Lisbon, Portugal Ms. 72), begun in July 1299 and completed in the following year in May. Illuminated by Yosef Asarfati (or Tzarfati, i.e., “the French”) and sometimes called the Sarfati Bible, it includes one of the most iconic images of the Temple Menorah, as well as detailed decorations. The colophon features giant animal-form letters (see images here). The Cervera Bible includes before and after it a copy of Radak (R. David Kimchi)’s Sefer ha-Michlol, a grammatical treatise in two parts.

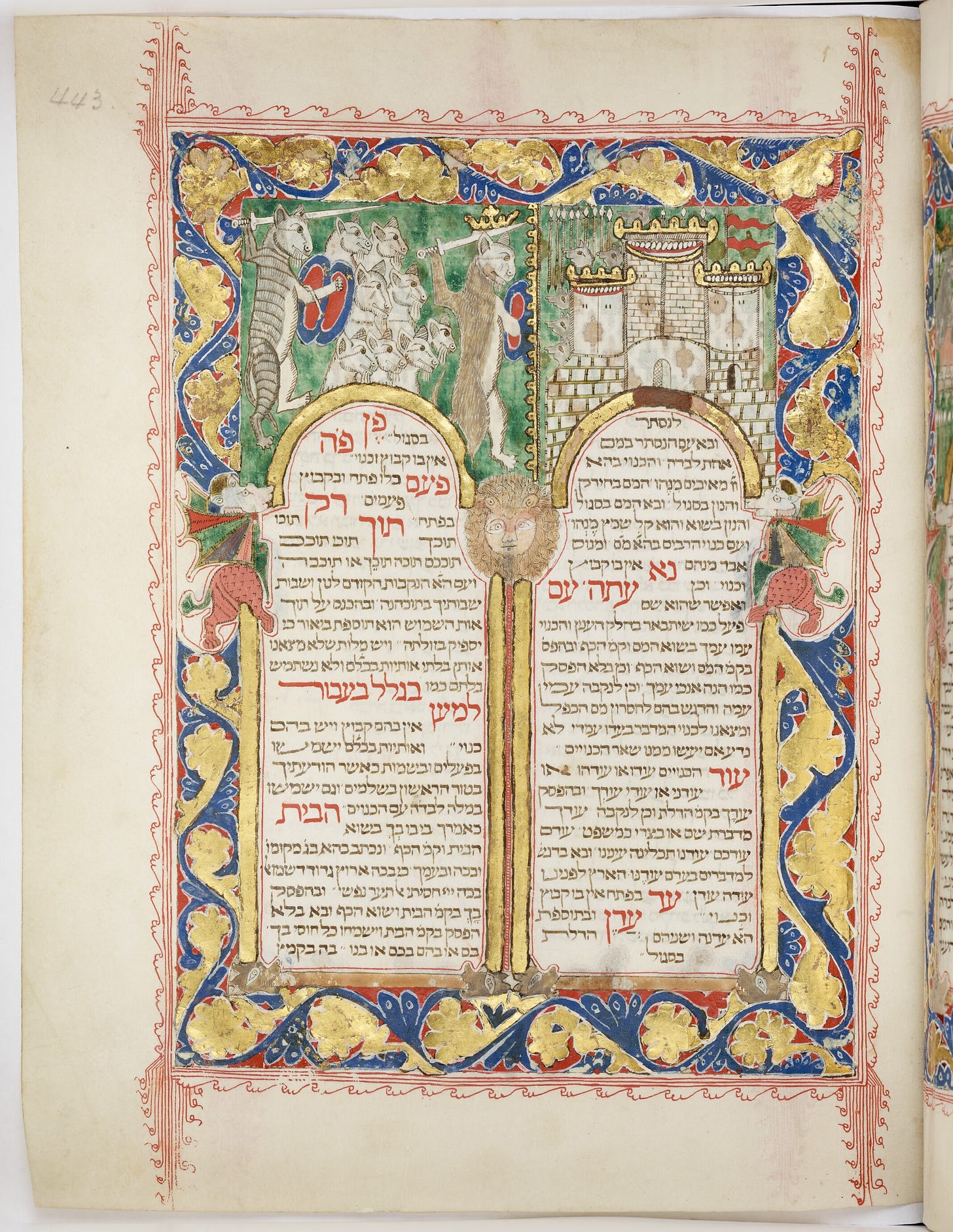

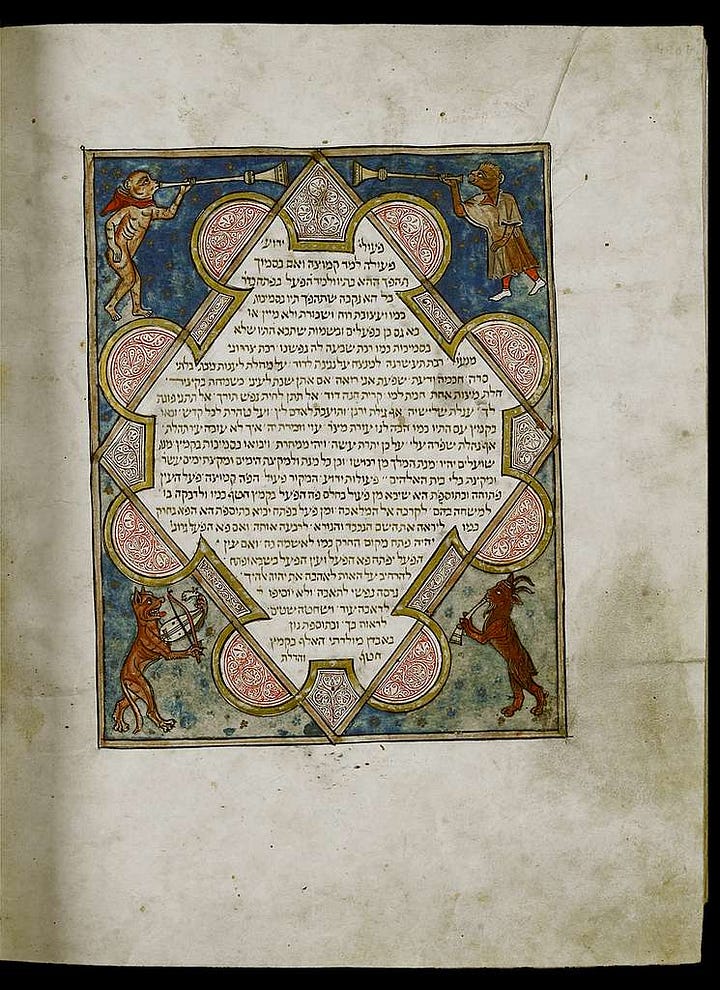

The magnificent Kennicott Bible (Bodleian Library MS. Kennicott 1) is replete with many detailed illustrative panels and frames, some incomplete. Like the Cervera Bible, it includes Radak’s Sefer ha-Michlol and features an animal-letter colophon (see here for the colophon and more images, including the box binding in which it traveled out of Iberia following the expulsion of 1492). The Kennicott Bible is the product of a collaboration between the scribe Moshe Ibn Zabara, who records that he completed writing and checking the manuscript in La Coruña in the year 1475/6; the skilled illuminator was Yosef Ibn Chaim.

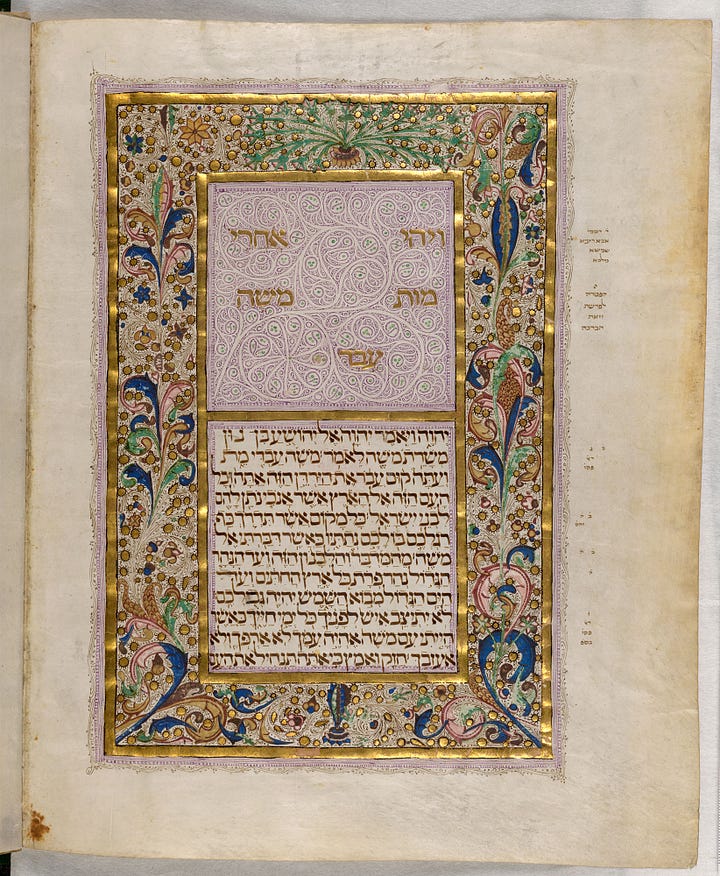

Finally, the Lisbon Bible (British Library Ms. Or. 2626, Or 2627, and Or 2628) is a complete Tanach in three volumes which shares with the Kennicott Bible the tendency to be labeled “the finest” of Sefardi illuminated Bibles. (Obviously, such rubrics are highly subjective.) Creating it was a team effort; it was written in 1482/3 by Shmuel ben Shmuel Ibn Musa in a square Sefardi script, and illuminated by several hands. Its nikkud (vowelization) and Masoretic notes are regarded as particularly skillful and accurate.

Reading & Resources

Tablet has an article, Everything is Illuminated (oh, if only it was!), with a slide show, covering an exhibition at the Met of three of the Bibles featured above.

One of the world experts on Hebrew manuscripts introduces the Kennicott Bible in this video.

Most facsimile editions are prohibitively expensive, but there is a (still pricey, but non-exorbitant) edition of the Kennicott Bible available on Amazon.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective.

> This manuscript of Neviim (the Prophets section of the Bible) includes Targum Onkelos, the canonical Aramaic translation of the Biblical text, but also, unusually, includes Rashi’s commentary.

Presumably this is the Targum Yonatan, not Onkelos?