The Aliyah of 300 Rabbis in 1211

🗺️ In the early twelfth century, several groups of learned Jews, mainly from France, England, and Provence, reached Eretz Yisrael. What do we know about their journey and motivations?

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. Today we’re continuing our adventures in premodern Eretz Yisrael with the aliyah of “three hundred rabbis” from Ashkenaz. A variety of sources testify to their efforts to travel and settle in the Land, though their motivations are the subject of scholarly debate. I tend to think, as with so many historical events, it’s multifactorial. We’ll explore below.

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here.

In this issue:

A thirteenth-century source records that three hundred rabbis from France and England made aliyah to Eretz Yisrael in the year 4971 (1210/11). This source was copied as an appendix to Shevet Yehuda, a sixteenth-century historiographical work by R. Shlomo Ibn Verga, a Sefardi Jew who escaped from Málaga in southern Spain to Lisbon, Portugal, and finally to Ottoman Turkey. Shevet Yehuda was published by Ibn Verga’s son, Yosef, who added material to it, including this copy of a chronicle he found in the library of one Yom Tov Sanzolo. The rabbis are sometimes referred to as Tosafists, although the relatively small size of Ashkenazi communities coupled with what is known about the demographics of the Tosafist enterprise make it unlikely that they were all Tosafists. However, there is evidence that the group consisted of learned, pious Jews and their families—and that there were, indeed, waves of rabbis who made aliyah around this year.

What We Know About the Aliyah of 1211

A number of early sources attest to the presence of a group of Ashkenazi immigrants in the Land of Israel in the early thirteenth century. The poet Yehuda al-Harizi—a pen name that means “of the rhyme” and alludes to his Arabic literary model, al-Hariri of Basra—traveled to the Land of Israel, recording some of his experiences in his book of maqamat, Hebrew rhymed prose, in this case, embedded in a frame story, as well as in a travel narrative. In Tachkemoni 46, al-Harizi records that he was in Jerusalem in 1216 and met there several French scholars, mentioning “men of great piety who came from the land of France to dwell in Zion” (חסידי עלין הבאים מארץ צרפת לשכון בציון—notice the rhyme in the Hebrew!). In his Milchamot Hashem, written in 1235, R. Avraham the son of Rambam also mentions a group of French scholars who made aliyah and passed first through Egypt, where he lived. Another important source is a letter written by one R. Shmuel ben R. Shimshon, who traveled from France with the prominent Provençal rabbi, R. Yonatan ha-Kohen of Lunel. It has been suggested that he was the son of R. Shimshon of Sens, who, as we’ll soon see, was part of the aliyah. We’ll take a closer look at this letter below.

As mentioned, the aliyah of the three hundred rabbis is sometimes known as the aliyah of the Tosafists, that is, drawn from the Ashkenazi rabbis who were responsible for the generations-long dialectical commentary on the Talmud Bavli known as Tosafot (literally, “Additions”—almost certainly in reference to the line commentary of Rashi). We do know that several prominent Tosafists were among the rabbis who made it to Eretz Yisrael in the early thirteenth century, as well later in the thirteenth century. These include R. Baruch ben Yitzchak of Worms (mentioned in an obscure chronicle published by Israel M. Ta-Shma); R. Yosef of Clisson—known in the Tosafot as Ish Yerushalayim, “a man of Jerusalem”—and his brother R. Meir (mentioned by al-Harizi); possibly R. Shimshon “ha-Sar” of Coucy (mentioned in a unique manuscript also published by Ta-Shma); and R. Shimshon of Sens (mentioned by R. Avraham ben ha-Rambam). The representation of Tosafists in this aliyah is undoubtedly striking, although, considering that the enterprise continued to flourish in Europe, it’s unlikely that they numbered three hundred, which would have decimated the movement. Rather, it seems that the aliyah drew members of the educated class from France and England. The question is: why?

What Inspired the Rabbis to leave Europe and Make Aliyah?

Ephraim Kanarfogel has argued compellingly that a major driver of the aliyah of the French rabbis was the religious desire to be able to perform more mitzvot (Torah commandments). He notes the trend of Tosafist practical interest in commandments that can only be performed in Eretz Yisrael, in the spiritual merits of making aliyah, and in agricultural mitzvot, omitted from the discussion that constitutes the Talmud Bavli, itself a product of a diaspora community. While there were other forces, they were subordinate, on Kanarfogel’s read, to the spiritual dimension.

These forces were not insignificant. In concert with their spiritual motivation, Jews in early thirteenth-century Ashkenaz were facing increased persecution—in France, Germany, and England. Experimentations with local and regional expulsions of Jews began in the late twelfth century in northern France (French Crown lands) and England. These would later result in kingdom-wide expulsions. The mendicant movement, a Christian protest movement that was eventually channeled and subsumed into monastic life, was picking up steam in the earlier thirteenth century, particularly in Italy and southern France. The mendicant friars would spearhead a new conception of theological anti-Judaism that sought conversion as opposed to toleration, if in a state of debasement. In addition, heavy taxation by the French Crown placed severe strain on French Jewish households. Robert Chazan has argued that economic and political forces were motivating factors in the aliyah of 1211.

R. Shmuel ben R. Shimshon’s Account

R. Shmuel’s account was truncated by the copyist to emphasize the graves of holy figures, an enduring area of interest for those making aliyah, as we’ve seen in the accounts of R. Petachia of Regensburg and R. Binyamin of Tudela. R. Shmuel traveled from Europe via Egypt, the Jewish community of which had close ties to the communities in the Land of Israel. These included missions to collect monies on behalf of impoverished students in various cities in the Land of Israel. Traveling along with R. Shmuel were as well as two students, R. Saadia and R. Tuvia, as well as R. Yonatan ha-Kohen of Lunel, one of the great sages of Provence.

Known through the ages mostly by quotation by other Rishonim, R. Yonatan wrote extensive commentaries on the Talmud and on the Rif; the Talmud commentaries remained in manuscript until modernity. He was also known for his role in one of the earliest of the Maimonidean controversies, a set of cultural debates over the reception of the works of the Rambam which began in his lifetime and stretched on into the fourteenth century (arguably, until the present). In it he emerged as a defender of Rambam and his works. R. Yonatan himself engaged in correspondence, chiefly halachic, with Rambam, which left Rambam with a deeply favorable impression of Provençal Jewry. Rambam enclosed copies of both Mishneh Torah and, later, Moreh ha-Nevuchim (Guide of the Perplexed), in letters to R. Yonatan. It was R. Yonatan who gave the Moreh to R. Shmuel Ibn Tibbon, who translated it in the version best known to Hebrew-reading audiences.

Notice the pious practices and deep emotion of the party as they enter the holy sites of Jerusalem:

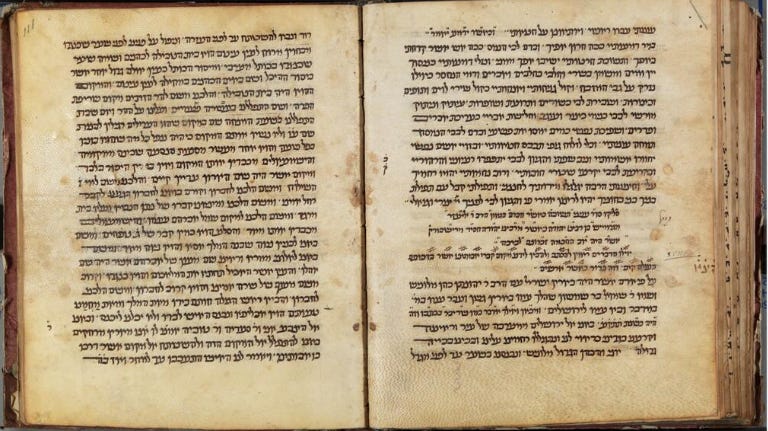

באנו אל ירושלים ממערבה של עיר וראינוה וקרענו בגדינו כראוי לנו, ונתגוללו רחמינו עלינו ובכינו בכייה גדולה אני והכהן הגדול מלוניש. ונכנסנו בשער עד לפני מגדל דוד ונבא להשתטח עד לפני העזרה. וניפול על פנינו לפני שער שכנגדו מבחוץ מרוח לעין עיטם הוא בית הטבילה לכהנים ושמה שער שכנגדו בכותל מערבי ומיסוד הכותל כעין אולם גדול אחד אשר ביסוד ההיכל, ושם באים הכהנים במחילה לעין עיטם. והמקום ההוא היה בית הטבילה.

We approached Jerusalem from the west of the city and, seeing it, we rent our garments as is incumbent upon us. Our compassion was aroused and we wept, a great weeping, myself and the great Kohen from Lunel. We entered the gate and went up to the Tower of David, then came and prostrated ourselves upon the Temple court [Azarah]. We fell on our faces opposite the gate, which, beyond it, is a clearing for the spring of Eitam that serves as the site of immersion for the priests. There, opposite it, is the gate to the Western Wall [Kotel Maaravi]. From its foundation the Wall appears like one great hall that is at the foundation of the Heichal [inner chamber], and from there the priests come in absolution to the spring of Eitam. That place was the place of immersion.

The Letter of R. Shmuel ben R. Shimshon, ed. Yaari in Igerot Eretz Yisrael, p. 78.

R. Shmuel has a keen interest in identifying the specific sites of the destroyed Temple, and his description reads as though he is imagining—and to the extent possible, reenacting—the ancient ritual. The wound is still fresh, over a thousand years later: though certainly a pious custom, evident here is the sense of emotional immediacy in tearing kriya (the halachic practice of rending one’s garments upon seeing or hearing of a close person’s death) for Jerusalem. R. Shmuel also details the heightened experience of praying at the holy sites along with his companions. Eight centuries ago, a man walked from France to the Middle East in order to see with his own eyes the places invoked in daily prayer and make his home in his ancestral land.

Reads and Resources

You can read R. Shmuel bar Shimshon’s letter in Avraham Yaari’s אגרות ארץ ישראל (Tel Aviv, 1943). The digital copy on HebrewBooks is, unfortunately, a bit worse for the wear, with low-res type and some missing portions at the tops of the pages, but it’s still readable.

Ephraim Kanarfogel’s masterful article on this subject is: “The ‘Aliyah of “Three Hundred Rabbis’ in 1211: Tosafist Attitudes toward Settling in the Land of Israel,” Jewish Quarterly Review 76 (1986). It’s freely available at the link thanks to the YU repository.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective. If you’d prefer to make a one-time donation in any amount, you can do that easily through my page at Ko-fi. Thank you so much.

Perhaps these Baalei Tosfos made aliyah because they realized that Jewish life and the transmission of Torah in France at the time of the Crusades was no longer viable

Thank you. The link to אגרות ארץ ישראל is broken.