The Journey of Yehuda ha-Levi

🌅 Sefarad's golden boy turns his back on courtly pleasures and sets his sights on his once and future country.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. Thank you so much to all who wrote to me following the previous message. I am so glad to know that you found some small measure of comfort in my words and I read each email and message with care. Please accept my sincere apologies for not writing to each of you individually—I can’t say I’ve had much presence of mind in the past days, and I am also on mobile this week (hi from New York City!). But please know how appreciated you are. And now, let’s go hang out with the one and only R. Yehuda ha-Levi.

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here.

In this issue:

A Young Poet Rises

R. Yehuda ha-Levi (c. 1075-1141) was born on the northern edge of Muslim Spain, in the city of Tudela, and spent a chunk of his life in the Christian part of Spain, though his intellectual formation and the vast majority of his adult years were spent in the Islamicate sphere. Notwithstanding, his classical Judeo-Arabic education and his social connections render him perhaps the apotheosis of Jewish life in al-Andalus. He was reputedly catapulted to stardom in a poetry slam (yes, really; poetry competitions were an important element of elite culture, and Hebrew poetry “battles” were modeled on Classical Arabic ones), in which Yehuda ha-Levi successfully and on the fly improvised an extraordinarily complex imitation of a poem by the poet’s poet himself, R. Moshe Ibn Ezra, who we met last time. Moshe Ibn Ezra declared him the victor and took him under his wing. In this youthful stage, Yehuda ha-Levi was known for his poems on the good life as well as in praise of the rich and powerful.

But gradually, something inside of Yehuda ha-Levi began to shift. This is perhaps nowhere better illustrated than in his poem, Me’az meon ha-ahava hayita. The poem employs a trope well-known to Arabic love poetry, in which the forlorn lover celebrates the scorn of his beloved with self-abnegation. The language is the language of “secular” love poetry, the poet welcoming his dark fate since it, too, alas, binds him to his beloved. In fact, the scholar Y. Levin made the remarkable discovery that Ha-Levi’s poem is in actuality a translation of an Arabic secular (as in erotic) love poem by the poet Abu al-Shis, who lived in the eighth to ninth centuries. All of it, that is, except for the last line:

מֵאָז מְעוֹן הָאַהֲבָה הָיִיתָ –

חָנוּ אֲהָבַי בַּאֲשֶׁר חָנִיתָ.תּוֹכְחוֹת מְרִיבַי עָרְבוּ לִי עַל שְׁמָךְ,

עָזְבֵם – יְעַנּוּ אֶת‑אֲשֶׁר עִנִּיתָ.לָמְדוּ חֲרוֹנְךָ אוֹיְבַי – וָאֹהֲבֵם

כִּי רָדְפוּ חָלָל אֲשֶׁר הִכִּיתָ.מִיּוֹם בְּזִיתַנִי בְּזִיתִינִי אֲנִי,

כִּי לֹא אֲכַבֵּד אֶת‑אֲשֶׁר בָּזִיתָ –עַד יַעֲבָר‑זַעַם וְתִשְׁלַח עוֹד פְּדוּת

אֶל‑נַחֲלָתְךָ זֹאת אֲשֶׁר פָּדִיתָ.From time’s beginning, You were love’s abode /

My love encamped wherever it was You tented.The taunts of foes for Your name’s sake are sweet, /

So let them torture one whom You tormented.I love my foes, for they learned wrath from You, /

For they pursue a body You have slain.The day You hated me I loathed myself, /

For I will honor none whom You disdain.Until your anger pass, and You restore /

This people whom You rescued once before.Yehudah ha-Levi, Me’az meon ha-ahava, trans. Raymond P. Scheindlin, The Gazelle: Medieval Hebrew Poems on God, Israel, and the Soul (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1991), pp. 76-83.

In Ha-Levi’s hands, the jilted lover becomes Israel and the elusive beloved, G-d. He has transformed it into religious love poetry: an anthem for a long-suffering people persisting in long exile. This is also the reason for the note of nechama, of comfort and hope, with which the poem concludes and upon which it turns. Unlike the cruel beloved, G-d will remember His actions in history and return to Israel. But it is not only in the last line that we come to know that the poem has been transformed into an ardent prayer. It is also in the very translation, which Ha-Levi imbues with language lifted from Tehillim (Psalms). Compare: Tehillim 69 (selections):

רַבּ֤וּ ׀ מִשַּׂעֲר֣וֹת רֹאשִׁי֮ שֹׂנְאַ֢י חִ֫נָּ֥ם עָצְמ֣וּ מַ֭צְמִיתַי אֹיְבַ֣י שֶׁ֑קֶר אֲשֶׁ֥ר לֹֽא־גָ֝זַ֗לְתִּי אָ֣ז אָשִֽׁיב׃ [ה]

כִּֽי־עָ֭לֶיךָ נָשָׂ֣אתִי חֶרְפָּ֑ה כִּסְּתָ֖ה כְלִמָּ֣ה פָנָֽי׃ [ח]

מ֭וּזָר הָיִ֣יתִי לְאֶחָ֑י וְ֝נׇכְרִ֗י לִבְנֵ֥י אִמִּֽי׃ [ט]

כִּֽי־קִנְאַ֣ת בֵּיתְךָ֣ אֲכָלָ֑תְנִי וְחֶרְפּ֥וֹת ח֝וֹרְפֶ֗יךָ נָפְל֥וּ עָלָֽי׃ [י]

וָאֶבְכֶּ֣ה בַצּ֣וֹם נַפְשִׁ֑י וַתְּהִ֖י לַחֲרָפ֣וֹת לִֽי׃ [יא]

וְאַל־תַּסְתֵּ֣ר פָּ֭נֶיךָ מֵעַבְדֶּ֑ךָ כִּי־צַר־לִ֝֗י מַהֵ֥ר עֲנֵֽנִי׃ [יח]

קׇרְבָ֣ה אֶל־נַפְשִׁ֣י גְאָלָ֑הּ לְמַ֖עַן אֹיְבַ֣י פְּדֵֽנִי׃ [יט]5 More numerous than the hairs of my head are those who hate me without reason; Many are those who would destroy me, my treacherous enemies. Must I restore what I have not stolen? …

8 It is for Your sake that I have been reviled, that shame covers my face;

9 I am a stranger to my brothers, and alien to my kin.

10 My zeal for Your house has been my undoing;

The reproaches of those who revile You have fallen upon me.11 When I wept and fasted, I was reviled for it. …

18 Do not hide Your face from Your servant, for I am in distress; answer me quickly.

19 Come near and redeem me; free me from my enemies.

Ha-Levi finds an analogy to the love trope in the language of the scriptures, and brings it powerfully to bear upon a worldly poem. He has transformed it not only from chol (everyday) to kodesh (holiness), but, in due time, he will transform himself along this trajectory as well.

The Radicalism of The Kuzari

R. Yehuda ha-Levi wrote philosophy as well, though it would perhaps be more accurate to call it anti-philosophical or supra-rational, even as he worked in established genres of rationalist philosophical writing. In the book known generally as The Kuzari (The Khazarian), written in Arabic under the title translated as The Book of Refutation and Proof on Behalf of the Despised Faith, he employs the classical mode of the philosophical dialogue. It begins with the dream of a king of the Khazars, purportedly a kingdom roughly in the Crimea. There is strenuous debate, scholarly and popular, about the historicity of the claim that the Khazars converted en masse to Judaism, which we will have to leave to a future newsletter. For now, it’s important to note that those scholars who accept the evidence of an event of this nature emphasize that the move was likely made out of political expediency, given that Khazaria was probably located on the border of Christian and Muslim lands. For the purposes of Ha-Levi, what was important was his dream—that somewhere, a people wanted to opt into the “despised faith”—and the dream of the fictional protagonist, the Kuzari, who was told repeatedly, if a (recurring) dream is one-sixtieth of prophecy (Berachot 57b), that his spiritual intentions were pure but his actions were not. The Kuzari sets out to determine what religion would fit his needs and make his actions worthy. He consults a philosopher, a Christian scholar, a Muslim scholar, and, when they fail him, finally, a chaver (scrupulous rabbi). In contradistinction to the previous interlocutors of the Khazar king, the rabbi opens his salvo thus:

אָמַר לוֹ הֶחָבֵר: אֲנַחְנוּ מַאֳמִינִים בֵּאלֹהֵי אַבְרָהָם יִצְחָק וְיַעֲקֹב הַמּוֹצִיא אֶת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל מִמִּצְרַיִם בְּאוֹתוֹת וּבְמוֹפְתִים וּבְמַסּוֹת, וְהַמְכַלְכְּלָם בַּמִּדְבָּר, וְהַמַּנְחִילָם אֶת אֶרֶץ כְּנַעַן, אַחַר אֲשֶׁר הֶעֱבִירָם אֶת הַיָּם וְהַיַּרְדֵּן בְּמוֹפְתִים גְּדוֹלִים, וְשָׁלַח משֶׁה בְתוֹרָתוֹ, וְאַחַר כָּךְ כַּמָּה אַלְפֵי נְבִיאִים אַחֲרָיו מַזְהִירִים עַל תּוֹרָתוֹ, מְיַעֲדִים בִּגְמוּל טוֹב לְשׁוֹמְרָהּ, וְעֹנֶשׁ קָשֶׁה לַמַּמְרֶה אוֹתָהּ. וַאֲנַחְנוּ מַאֲמִינִים בְּכָל מַה שֶּׁכָּתוּב בַּתּוֹרָה, וְהַדְּבָרִים אֲרֻכִּים

The Rabbi replied: I believe in the G-d of Abraham, Isaac and Israel, who led the children of Israel out of Egypt with signs and miracles; who fed them in the desert and gave them the land, after having made them traverse the sea and the Jordan in a miraculous way; who sent Moses with His law, and subsequently thousands of prophets, who confirmed His law by promises to the observant, and threats to the disobedient. Our belief is comprised in the Torah—a very large domain.

The Kuzari, Book 1, trans. Hartwig Hirschfeld

The claim is specifically an historical one: it is based not on independent logic but on particular events happening in a discrete time and place, verified by a chain of transmission made up of thousands of authorities. It is, as the Kuzari observes, unconvincing on its face; one must take it at its word. But it is also impervious to logical challenge; it is, as the rabbi takes time to point out, an active and experiential practice. It explains to the king what his deeds are to be. And he finds them pleasing, converting to Judaism early in the book. The remainder, then, is further explanation made to an initiate.

As a part of the dialogue, the rabbi and the king speak about the sanctity and special status of the Land of Israel. The king, hearing the Land extolled, wonders why the rabbi does not trouble himself to go there, to make aliyah. The rabbi responds: “This is a severe reproach, O king of the Khazars” (Kuzari, Book 2). It is the seed of an idea that will bear fruit by the book’s end, when the rabbi announces that he is departing for Eretz Yisrael. It will turn out that the rabbi is, like at so many points throughout the book, acting as the mouthpiece of his author: R. Yehuda ha-Levi was to turn his back on the pleasures of Spain and set sail across the Mediterranean on aliyah.

His parting words to the Kuzari capture the essence of Ha-Levi’s repudiation of the culture with which he was so readily identified, an identification that made him a celebrity, hounded at each port of call at which he landed. (He refused the many calls to stay and went resolutely eastwards.) Ha-Levi/the rabbi explain poignantly that they are turning from worldliness to spiritual elevation:

אָמַר הֶחָבֵר: אֲבָל אֲנִי מְבַקֵּשׁ הַחֵרוּת מֵעַבְדוּת הָרַבִּים אֲשֶׁר אֲנִי מְבַקֵּשׁ רְצוֹנָם וְאֵינֶנִּי מַשִּׂיגוֹ, וַאֲפִלּוּ אִם אֶשְׁתַּדָּל בּוֹ כָּל יְמֵי חַיָּי, וְאִלּוּ הָיִיתִי מַשִּׂיגוֹ לֹא הָיָה מוֹעִיל לִי, רְצוֹנִי לוֹמַר: עַבְדוּת בְּנֵי אָדָם וּבַקָּשַׁת רְצוֹנָם. וַאֲבַקֵּשׁ עַבְדוּת אַחֵר, יֻשַּׂג רְצוֹנוֹ בְטֹרַח מְעָט, וְהוּא מוֹעִיל בָּעוֹלָם הַזֶּה וּבַבָּא, וְהוּא "רְצוֹן הָאֱלֹהִים", וַעֲבוֹדָתוֹ הוּא הַחֵרוּת הָאֲמִתִּי, וְהַהַשְׁפָּלָה לוֹ הוּא הַכָּבוֹד עַל־הָאֱמֶת.

The Rabbi: I only seek freedom from the service of those numerous people whose favour I do not care for, and shall never obtain, though I worked for it all my life. Even if I could obtain it, it would not profit me—I mean serving men and courting their favour. I would rather seek the service of the One whose favour is obtained with the smallest effort, yet it profits in this world and the next. This is the favour of G-d, His service spells freedom, and humility before Him is true honour.

Voting with His Feet

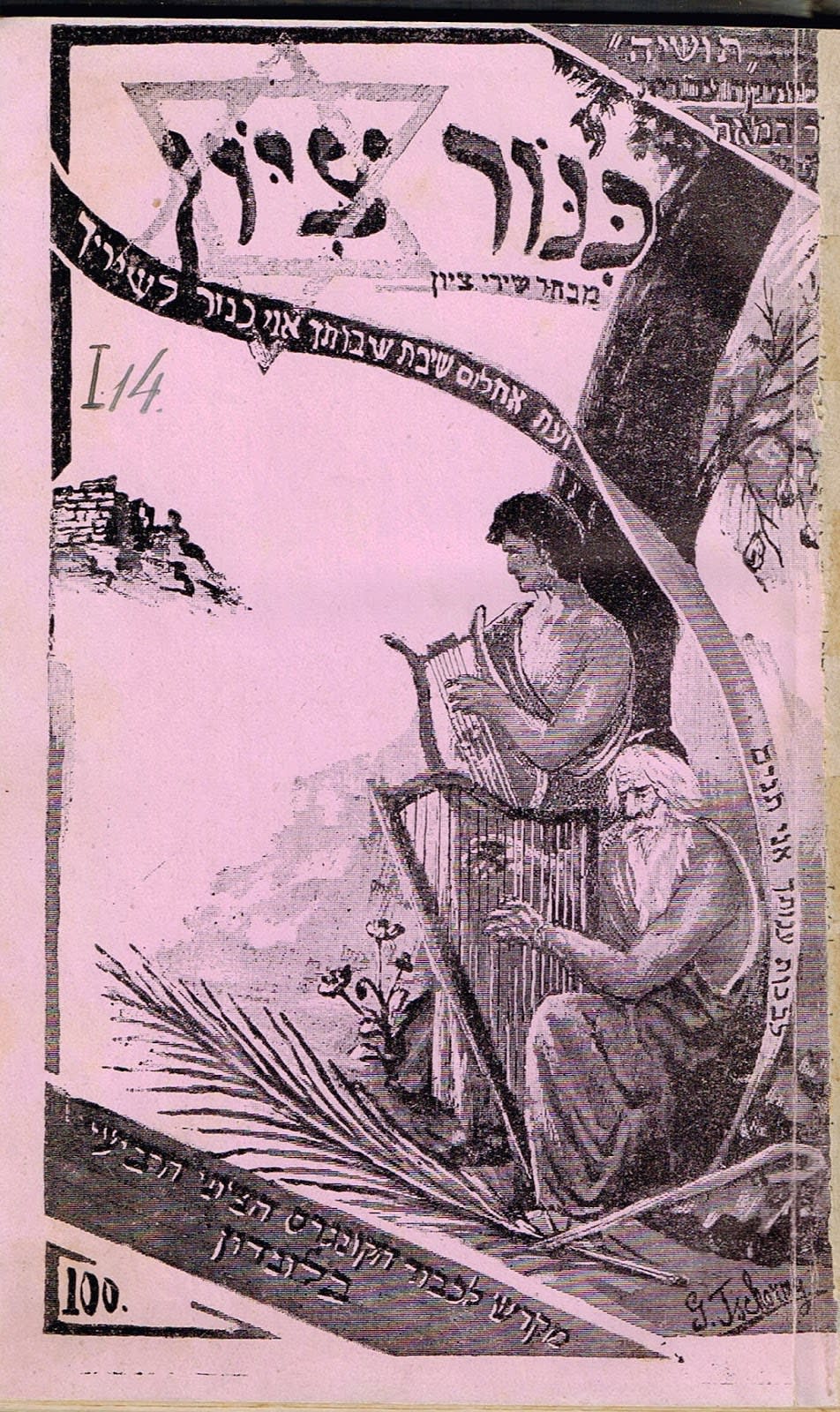

R. Yehuda ha-Levi actualized his poetically-expressed longing for the spiritual life and Zion. Among his most famous “Zionides,” or odes to the Land of Israel, is Tziyon ha-lo-tishali:

צִיּוֹן, הֲלֹא תִשְׁאֲלִי לִשְׁלוֹם אֲסִירַיִךְ,

דּוֹרְשֵׁי שְׁלוֹמֵךְ וְהֵם יֶתֶר עֲדָרָיִךְ?

מִיָּם וּמִזְרָח וּמִצָּפוֹן וְתֵימָן שְׁלוֹם

רָחוֹק וְקָרוֹב שְׂאִי מִכֹּל עֲבָרָיִךְ,

וּשְׁלוֹם אֲסִיר תַּאֲוָה, נוֹתֵן דְּמָעָיו כְּטַל–

חֶרְמוֹן וְנִכְסַף לְרִדְתָּם עַל הֲרָרָיִךְ!

לִבְכּוֹת עֱנוּתֵךְ אֲנִי תַנִּים, וְעֵת אֶחֱלֹם

שִׁיבַת שְׁבוּתֵך – אֲנִי כִנּוֹר לְשִׁירָיִךְ.Zion, do you ask if the captives are at peace—

the few that are left?

I cry out like the jackals when I think of their grief;

but, dreaming of the end of their captivity,

I am like a harp1 for your songs.From the Songs of Zion, translated by Charles Reznikoff

This poem, in addition to its general renown, also caught the hearts of later poets. Charles Reznikoff (1894-1976), the son of Jewish immigrants from Russia to the United States following the pogroms of the 1880s, tenderly translated a selection of the Zionides. He used these, alongside his own poetry, to express the dislocation he felt from both his parent’s home culture and that of America. And it was famously paraphrased by Naomi Shemer in the popular song “Yerushalayim shel Zahav” (Jerusalem of Gold): “I am a lyre for all your songs” (הלא לכל שירייך אני כינור). Incidentally, when I was a child, I thought the word nechoshet (“bronze”) in the song was choshech, making it, “Jerusalem of gold, of darkness and of light”—kind of like Yeshayahu 45:7, יוצר אור ובורא חשך. I thought it strikingly beautiful for the acknowledgement of joy and pain bound up in the holy city. Sentiments that feel all too close these days. Hachi garsinan (and so I will read it): darkness and light.

Reads & Resources

More about Charles Reznikoff at the Poetry Foundation.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective.

The meaning of the biblical Hebrew word kinor probably means a stringed instrument more like a lyre or harp, but in modern Hebrew it denotes a violin. The Hebrew word is the same in ha-Levi and Shemer.

Great post, and even greater punchline. שנשמע ונתבשר בשורות טובות

Great post, thanks for explaining so well R' Halevi's complex life. R' Halevi was singular in the Andalusian school in how he synthesized different approaches to Jewish thought, becoming, as you wrote, the anti-philosophical philosopher.

I've learned the Kuzari many times, teach a weekly class on it, and much of my worldview is based on this wonderful book.

In the coming weeks I'll be writing about the Land of Israel; many themes from the Kuzari will be in the background.

May we hear good news.