The Last Maimonidean Controversy? The Controversy of 1304-1307

🎓 We have a rich trove of sources documenting the Maimonidean controversy of 1304-1307, which drew in the Rashba, allowing us to see how the nature of the Maimonidean controversies shifted.

First, I want to send out my gratitude and appreciation to all the many of you who wrote to me after the last announcement—I’m so sorry I wasn’t able to respond to each individually, but please know that I read each message, and that they mean a great deal to me. Life has been busy and full. This is a year of leaps of emunah (faith) for me and my family without a lot of certainties, except that we’re moving boldly in the direction of our dreams. I hope this will mean lots more writing for me.

In the meantime, I’ve missed writing for you very much and I’m happy to be back in this space with the concluding post in the Maimonidean controversies series. This subject is particularly near to my heart (and mind), being the subject of my doctoral dissertation. It still fascinates me after many years of research. It was a challenge to distill the many twists and turns of this last of the medieval controversies into short form, but I hope it gives you an overview of the core elements of the debate and piques your curiosity about how this fourteenth-century affair still resonates today.

In this issue:

The Maimonidean controversy of the early fourteenth century is different in kind from those that preceded it: it was no no longer a dispute about the place of the Rambam’s works in the Jewish canon—including his controversial inclusion of dogma in his code of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah (also controversial due to its lack of sources throughout), as well as the Aristotelian-inflected contents of his elite philosophical work, Moreh ha-Nevuchim (The Guide of the Perplexed). Both Rambam’s proponents and his detractors in this later cultural debate accepted the value and legitimacy of these two key works and of Rambam’s philosophical project. All refer to him in respectful terms. The concern now turned to philosophy in general, particularly non-Jewish, Aristotelian philosophy. Was its method a danger to young, impressionable minds? Should cultural access to philosophy be limited in the Jewish community?

R. Abba Mari’s Goals and Tactics

The instigator of the fourteenth-century controversy was one R. Abba Mari ben Moshe ha-Yarchi (“of Lunel”), a smalltime intellectual living in Montpellier. (Lunel was renowned as a city of scholars, so those whose families once lived there tended to lay claim to it.) Though sometimes depicted in the scholarly literature as a resolute conservative, R. Abba Mari was neither anti-intellectual nor reactionary, but a middle-of-the-road, not atypical member of the educated class of Provençal Jewry. His concern was about the popularization of Aristotelian philosophy and its undue influence on young minds not yet fully immersed in Torah learning. Among other complaints, he noted, and there is some evidence to back up the accusation, that some of the more rationalist-minded intellectuals in Provence had taken to promoting a highly allegorized view of the narratives of the Torah, preaching such interpretations publicly on Shabbat afternoons in synagogues. A prevalent view, attacked vociferously by opponents in singsong prose, was the suggestion that Avraham and Sarah were not historical individuals but allegorical figures representing Form and Matter, respectively. (In the rhyming taunt, “Avraham and Sarah” were juxtaposed to chomer ve-tzurah, “matter and form,” due to the necessity of rhyming; but Sarah, being female, was identified in the medieval period with the lowlier Matter while Avraham, the male, was associated with the higher Form.)

R. Abba Mari’s opening gambit was a long shot, but a brilliant one: he attempted to reel in the leading authority of the age, the great Rashba of Barcelona, who headed the school of learning inherited from the epoch-making Ramban.

Though Barcelona, in Catalunya, lay jurisdictionally outside of Provence, Abba Mari was banking on the preeminent rabbi exerting his legal authority and cultural éclat into the neighboring region. R. Abba Mari first wrote to the Rashba regarding the use of medical talismans, a practice that emanated from the world of philosophical rationalism, which encompassed natural philosophy, or what we now call science, and its applied field of medicine, which had a strong astrological component. The medical talismans, decorative objects inscribed with meaningful symbols and used to ward off disease and medical catastrophe, particularly in childbirth, were not the central issue, but a hook to garner the involvement of Rashba. In fact, Rashba had already adjudicated the matter and, as he wrote back to R. Abba Mari with annoyance, circulated his responsa on the use of medical talismans widely, including in Provence. (Rashba ruled the talismans to be medicinal and permitted.)

In spite of this unpromising beginning, in which Rashba shrugged off the Provençal rabbi’s complaint, R. Abba Mari managed to achieve his goal. He had enough of an opening to inform Rashba of the allegorical preaching, teaching of philosophy to impressionable minds, and other such rationalist activities he regarded as dangerous to the core principles underlying Jewish life and ritual. Hearing R. Abba Mari’s reports, Rashba indeed became incensed and determined to act to limit the study of philosophy.

The ensuing dialogue between Rashba and his beit midrash in Barcelona and R. Abba Mari and his supporters in Montpellier and greater Provence was conducted via letters. These letters were sometimes private, written to individuals, and at other times public, addressed to a community writ large. As the cultural debate grew and became more rancorous, it drew in many additional voices from both Provence and Iberia, including the great Rosh, active in Toledo (in Castile, the heartland of Spain, further from France).

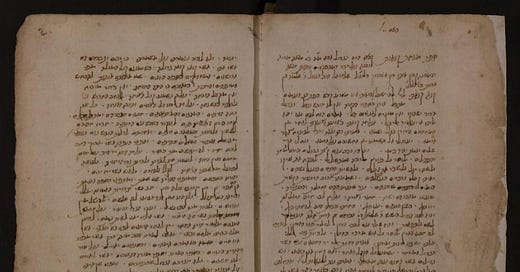

Remarkably, this multifarious epistolary controversy was preserved by R. Abba Mari himself, including not a few writings that were uncharitable towards him. (He also pledged to collect and edit the letters of his opponents, which, however, he was unable or unwilling to ultimately do, to the best of our knowledge.) R. Abba Mari not only collected the letters sent between Provence and Spain, but also edited them carefully into a book he titled Minchat Kenaot (Offering of Zeal),1 arranging them in a sensible order and writing headnotes to explain their context. He included within its pages a polemical manual for his supporters, the so-called anti-rationalist faction, titled Sefer ha-Yareach (Book of the Moon, a play on his name ha-Yarchi, a translation of Lunel). In many cases, R. Abba Mari preserved what book historians call paratextual features, meaning elements of a text outside the main body of writing. In Minchat Kenaot, that includes signatures and even the text that had been written on the outside of the sealed letter at the time of its delivery. This richness of detail makes the fourteenth-century controversy particularly illumined and thus illuminating.

R. Levi ben Avraham ben Chaim: An Actual Philosophical Heretic?

One of the first matters dealt with in the letter exchange recorded in Minchat Kenaot, after the establishment of the problem and the need to address it, is the matter of identifying the actual individuals who had transgressed communal boundaries in Provence. Rashba assumed that R. Abba Mari had in mind particular transgressors who needed to be reigned in, and was not just proposing an abstract debate with vague actors. R. Abba Mari, in turn, was prompted to find someone who fit the bill and demonstrated the pitfalls of popularizing philosophy. This he found in the person of one R. Levi ben Avraham ben Chaim (c. 1245–c. 1315) of the small town of Villefranche-de-Conflent.

R. Levi was the son of an established and respected family of the educated class of Provençal Jews,2 and by 1304 an older man. He was the author of two voluminous philosophical encyclopedias, Batei ha-Nefesh ve-ha-Lechashim (The talismans and the Amulets, from Yeshayahu 3:20) and Livyat Chen (Graceful Wreath, an allusion to Levi’s name lifted from Mishlei 1:9, repeated in Mishlei 4:9), only parts of which have been edited and published. Some of the ideas expressed therein accord broadly with the accusations levied against him, but Rashba’s response to the identification of Levi as a heretic is telling. Though Rashba was not typically restrained in the language he used for rationalists whom he considered dangerous, he ultimately treated R. Levi with nuance and even deference. Noting the problematics of Levi’s intellectual project, Rashba nonetheless expressed to him a sense that, between the two of them, he knew that R. Levi was not engaged in any heresy. However, Rashba proceeded to caution that for more impressionable minds, this type of material might well lead to heresy and to recommend strongly that its teaching and public dissemination be curtailed.

The Barcelona Ban and the French Expulsion

After a lull in the controversy over the winter of 1304-1305, apparently due at least in part to illness suffered by the Rashba, Barcelona leapt to action. The tool selected by Rashba and his supporters in the community was a particularly interesting one: the use of a ban of excommunication, which carried symbolic, but more importantly real, consequences. The mechanism of a ban (cherem) was a not-uncommon tool in the toolkit of the medieval posek (rabbinic authority), and included bans of various sorts, usually not involving heresy. There are two especially noteworthy aspects to the Barcelona community’s decision to enact a ban. The first is the reliance on a familiar legal mechanism, as opposed to novel means, such as the establishment of a creed. This, in fact, is what Rambam, at the center of the swirling controversies, himself attempted to do, first with the Thirteen Principles and later in Sefer ha-Madda.

The second noteworthy aspect of the ban is the scope chosen by the rabbis of Barcelona. Rather than issue the ban against individuals—such as R. Levi ben Avraham ben Chaim—or against concrete actions such as the production of philosophical tracts or the preaching of allegorizing sermons, the rabbis chose to ban the underage study of philosophy. There was a debate as to the age below which one should not be permitted to be instructed in rationalist philosophy of non-Jewish origin, with the moderate side winning the day. Accordingly, the age was reduced from forty, the traditional, though oft-disregarded, age for initiation into Kabbalistic secrets, to twenty-five years of age. How exactly was this to be enforced? The ban targeted teachers of philosophy rather than students, making the punishable offense the teaching of philosophy to others. This softened the effects of the Barcelona ban significantly, though it certainly did not erase them or their profound cultural message.

The rabbis of Barcelona saw their action as a catalyst for wider adoption of similar bans in other jurisdictions, and expected Montpellier to follow suit shortly thereafter. Instead rationalists in Provence issued counter-bans, this time targeting individuals, including Abba Mari. And then, the king of France intervened, if indirectly. Although the south of France (Occitania), which Jews called Provence, was ruled by a patchwork of counts, dukes, and other landed nobility, these were theoretically, and by the early fourteenth century increasingly, under the authority of the French Crown. Needing to raise monies for Crown, the king came upon the mechanism of expelling French Jews from the kingdom and its territories—collecting Jewish property and especially loan repayments to which they were entitled in the process.

Expulsions were a not infrequent fact of Jewish life in Europe, but had been limited, in the central Middle Ages, to local expulsions, which at least left dispossessed Jews with nearby options for resettlement. In the later centuries of the medieval period, however, monarchs began to experiment with larger-scale expulsions, usually motivated by the prospect of short-term financial gain (and certainly not helped by pervasive anti-Jewish attitudes in the Latin West). King Philip IV had taken note, and in July of 1306 issued a declaration of expulsion to French Jews. The upheaval of this act effectively brought the Maimonidean controversies to an end, though one wrought by circumstance and not by decision.

The Last Maimonidean Controversy?

R. Abba Mari, now a refugee, nevertheless found the wherewithal to assemble and edit Minchat Kenaot as he sought to resettle in Perpignan (not yet under French control) and ended up going east to Arles, one of the “Four Communities” where Jews found refuge under the Avignon papacy, which ruled the Comtat Venaissin. Evidently, he believed his struggle against potential heresy to be unfinished, and intended to take it up once again, something which did not come to pass. Thus the controversies ended on a technicality and not by dint of communal agreement or resolution.

History has not looked kindly upon R. Abba Mari and his mission, depicting him, often, as a representative of a close-mindedness that leads to self-defeating zealotry. This is, admittedly, how I expected to find him, and leave him, when I began my study of the documents of this controversy. I wound up in a very different place. I now see him as a prescient figure. Himself educated in the eminently rationalist tradition of Provençal Jewish learning, a kind of proto-Torah u-Madda, I believe that R. Abba Mari sincerely did not wish to stamp out the important possibilities of philosophy but rather to limit what he foresaw as its pitfalls. He anticipated, correctly, that taking some rationalist ideas to their logical conclusion would clash with the revelatory truths that underlie Jewish tradition. As the apparent contradictions between some aspects of Torah (the Jewish Bible) and Masorah (Jewish tradition) continue to bedevil us into postmodernity—arguably more than ever before—Abba Mari’s concerns are all too real. This is not to say that bans, or for that matter creeds, are the tools for the job, as the medieval community of Barcelona concluded with regard to the former. But addressing such contradictions directly and sensitively, which is what R. Abba Mari attempted, not entirely successfully, to do, remains a communal need.

Reads and Resources

Minchat Kenaot is printed with Rashba’s responsa, and was critically edited by the late H. Z. Dimitrovsky. The uncorrected text is available on Sefaria.

The literature about the last of the Maimonidean controversies is huge, and spread out not only in scholarship dedicated directly to the events and central figures of the controversy, but in related fields as well. As an entry point, I recommend the chapter on the controversy by Gregg Stern in The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Jewish Philosophy. (The whole volume is terrific.) Stern also has a (somewhat specialized) book on the controversy, Philosophy and Rabbinic Culture, which is, however, pricey.

Minchat Kenaot is a term taken from the ordeal of the Sotah, with the rationalists here pegged in the role of the Sotah

It has been suggested that the Ralbag (R. Levi ben Gershom) was related to him, though this is likely not the case.

Where can I read about what the rationalist education looked like during that time? I'm thinking of Shalom Sadiq's desire for revival, and wondering if there is precedent in communities being philosophical/rationalist, and note merely individuals.

Fascinating! Thank you again for the well researched and presented historical background of important medieval works.