The Sefardi Grammarians and their Battles

🌅 We move into the culture of Sefarad by unpacking a famous (and famously vicious) controversy over Hebrew grammar that broke out in the late ninth century.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. Today we get a juicy glimpse into the culture of medieval Sefarad by exploring a famous controversy among early grammarians of Hebrew with turned rather vicious before it was over. What could possibly inspire such vitriol in the name of morphology and syntax? Well, the meanings of words and the ways those meanings are carried, it turns out, can really get as the essence of things. The jury is still out on whether there was real heresy involved, as we’ll see.

Audio

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here.

In this issue:

There’s a saying about academia, the fights are so vicious because the stakes are so low. In the case of Hebrew grammar around the year 1000, however, the stakes were not actually low, as academic as such debates might seem today. What made them high? Well, for one, as was obvious to Jewish speakers of Arabic, Hebrew and Arabic are cognate languages. Arabic, however, was considered by the dominant Muslim culture to be the superior of all languages, uniquely pure and beautiful as it was used in the Quran. For another thing, there was a fierce contest over the precise transmission of the Biblical Hebrew corpus unfolding between Karaite and rabbinic Jews. And if that weren’t enough, the actual meanings of Biblical words had very real halachic and cultural implications.

The rise of a literature of Hebrew grammar grew out of the achievements of the Masoretes in the ninth and tenth centuries and their elaborate system of encoding grammatical information into the Masoretic markings, including vowel points and cantillation marks. The first Hebrew dictionary and the first systemic linguistic treatise both came from the pen of R. Saadia Gaon. After him, medieval Hebrew linguistics flowered for a relatively brief time in Muslim Spain before being transmitted, though little transformed, into Hebrew-literate Christian Europe. The achievements of the Sefardi grammarians continue to reverberate in modern Hebrew.

Dunash Ibn Labrat: Consumate Andalusi or Recalcitrant Outsider?

There can be no better introduction to the culture of Jewish al-Andalus than Dunash ben (or Ibn) Labrat’s1 poem Ve-omer al tishan. Possibly (more than possibly) I think that because it was, if memory serves, the first poem from medieval Sefarad I was assigned to read, translate, and explain as a young grad student. It made quite an impression. Let’s set it up first. Picture a stately courtyard, the kind filled with brilliantly-colored geometric tilework, potted fruit trees, and lion’s-head fountains. It’s the small hours of the morning, and an elegant young server flits between the men arrayed on their chaises, twirling wine glasses in their tiring hands. A musician in the corner is strumming his oud. The men are sporting, and their sport is poetry: the victory goes to he who spins words most skillfully, sometimes dizzingly so, according to elaborate rules the men all know even through their wine. None of this is quite true, but it is very much the imagined scene in which Dunash’s poem is set. It opens:

וְאוֹמֵר: ”אַל תִּישָׁן / שְׁתֵה יַיִן יָשָׁן

עֲלֵי מוֹר עִם שׁוֹשָׁן / וְכֹפֶר וַאְהָלִיםבְּפַרְדֵּס רִמּוֹנִים / וְתָמָר וּגְפָנִים

וְנִטְעֵי נַעְמָנִים / וּמִינֵי הָאְשָׁלִיםוְרֶגֶשׁ צִנּוֹרִים / וְהֶמְיַת כִּנּוֹרִים

עֲלֵי פֶה הַשָּׁרִים / בְּמִנִּים וּנְבָלִיםAnd he said: “Do not sleep! Drink old wine!”

Amid rose and myrrh, feast awayIn a pomegranate orchard, filled with date palms and grapevines

That extend amid tamarisks,Where the fountains splash and the hymns of ouds

compliment the singers and harps…

It goes on in this manner for a number of stanzas. And then—the turn:

גְּעַרְתִּיהוּ: ”דֹּם דֹּם / אֱלֵי זֹאת אֵיךְ תִּקְדֹּם

וּבֵית קֹדֶשׁ וַהְדֹּם / אֱלֹקים לָעְרֵלִיםבְּכִסְלָה דִּבַּרְתָּ / וְעַצְלָה בָחַרְתָּ

וְהֶבֶל אָמַרְתָּ / כְּלֵצִים וּכְסִילִיםוְעָזַבְתָּ הֶגְיוֹן / בְּתוֹרַת אֵל עֶלְיוֹן

וְתָגִיל וּבְצִיּוֹן / יָרוּצוּן שׁוּעָלִיםוְאֵיךְ נִשְׁתֶּה יָיִן / וְאֵיךְ נָרִים עָיִן

וְהָיִינוּ אַיִן / מְאוּסִים וּגְעוּלִים"

I chastised him: “Quiet! How can you go on like this

When the holy Temple of G-d belongs to the uncircumcised.You have spoken foolishly and chosen indulgence,

Spoken vainly like a boor or an idiot.You’ve abandoned the reason of the Torah of the highest One,

Will you really enjoy yourself while foxes run wild in Zion?How can we drink wine and lift our eyes

When we are nothing, hated and despised?

Dunash has captured for us the polarities of Jewish life in medieval al-Andalus: the cultural and material riches, the comradery—or at least the relative tolerance—enjoyed by the chattering classes on the one hand, and on the other, the reality of being a minority in exile, as another contrarian denizen of drunken poetry slams, R. Yehuda ha-Levi, would put it, “the edge of the West.” The voices—“Drink old wine!” “How can we drink?”—both belong, at once, to Dunash, as they did to many of his contemporaries.

The sober turn taken in the small hours by the poem’s narrator belies a stringent tendency in Dunash’s character, which later brought him to attack with viciousness his contemporary over a matter of…Hebrew grammar. In part, this was down to Dunash’s personality and his public persona; another important aspect of the puzzle is Dunash’s thorough and exacting knowledge of Hebrew grammar, which has been borne out by subsequent research.

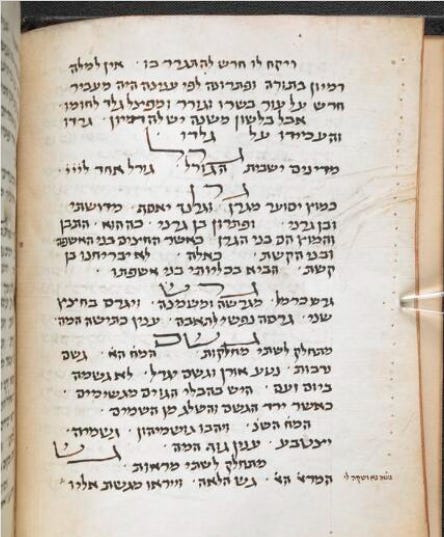

The Subject of the Attack: Menachem ben Saruk

Menachem ben (or Ibn) Saruk holds the distinction of writing the first Hebrew-Hebrew dictionary: that is, one in which the definitions are given in Hebrew, as opposed to Arabic, like his colleagues’ offerings. Menachem wrote his work, known as the Machberet, sometime in the latter half of the 900s; its original title may have been Sefer ha-Pitronim (The Book of Solutions), the term machberet generally denoting a smaller segment of a dictionary or other literary work, such as that devoted to words beginning with a given letter. Menachem’s work became the Machberet because it was the only classical Sefardi grammar produced in Hebrew, making it available to Jews outside of Arabophone areas. It was used extensively in Ashkenaz, notably by Rashi. (After the mid-twelfth century, following political upheavals in Sefarad, Sefardi emigres began translating and then producing their own works of Hebrew grammar, building heavily upon the classical works.)

Menachem ben Saruk wrote his dictionary under the tutelage of his patron, Chasdai (or Chisdai) Ibn Shaprut. He’d first worked under Chasdai’s father Yitzchak, then returned to Córdoba and begun working with his patron’s son’s support, still, however, enduring poverty. As well as writing superlative elegies for Chasdai’s parents, Menachem is credited with penning a famous letter to the Khazar king on Chasdai’s behalf. (Khazaria was a Crimean kingdom that had converted en masse to Judaism for reasons of political neutrality; it attracted the attention of Jews far and wide.) His dictionary was state-of-the-art at the time, though it would soon be superseded by important discoveries in Hebrew linguistics. Though non-systematic—Menachem tended to describe grammatical phenomena rather than theorizing it—he worked out an approach to the Hebrew root that assiduously avoided comparing the holy language to any other. As a result, he believed weak radicals to fall away and subscribed to the idea of words with one- or two-letter roots.

The Controversy Unfolds

These linguistic faults in Menachem’s Machberet were not, however, the reason he was targeted for intense criticism—on 180 numbered points3—by Dunash ben Labrat. Rather, Dunash attacked Menachem for wrongful interpretations of words which, Dunash maintained, could lead people to mistakes in halachic observance and even to heresy. The bitterness of the accusations has led to the question of whether Dunash was implicitly calling out Menachem as a Karaite. Research has not established a direct answer to that question, although Menachem’s demonstrable reliance on rabbinic tradition in several places seems to militate against him being a Karaite.

Things did not initially go well for Menachem; his patron, Chasdai Ibn Shaprut, dropped him for a time and he was impelled to leave Córdoba. He never raised his pen to defend himself, but three of his pupils did so in his stead: Yitchak Ibn Kapron, Yitzchak Ibn Gikatilla (or Chiqatillia—not to be confused by the eleventh-century, important grammarian Moshe Gikatilla), and one Yehuda ben David. This Yehuda has sometimes been identified with Yehuda Ibn Chayuj; what is certain is that Ibn Gikatilla was the teacher of Yonah Ibn Janach. Together, Ibn Chayuj and Ibn Janach would reach the pinnacle of Sefardi grammatical discovery. Notwithstanding, many of Dunash’s criticisms are considered linguistically valid.

Dunash does not seem to have harbored a personal grudge against Menachem; Menachem eventually got reinstated under Chasdai and ended up okay, to the best of our knowledge. Dunash’s ire, as outsized as it seems to us, was apparently the real deal. He really was concerned about the implications of Menachem’s linguistic verdicts. I actually think there’s something stunningly modern-feeling about it, for all its medieval abstruseness. Yes, it’s hard to imagine talking heads today bickering over a matter of grammar, you know, browbeating someone over a contested pluperfect. But it’s actually not at all that difficult to imagine “thought leaders” arguing over semantics, about the meanings that words bear (say, “female”) or, in our day (though not in Dunash and Menachem’s), even if they are capable of bearing definitive meaning at all.

Ibn Chayuj and the Discovery of the Triliterate Root

At the center of Menachem’s students’ counterattack on Dunash ben Labrat was Dunash’s application of Arabic poetic meter to Hebrew. This has a technical side to it: Arabic features long vowels that are audibly pronounced distinctly from short vowels. This would be like if you could hear the difference between a kamatz gadol (אָ) and a patach (אַ). Because this is natural in Arabic, Arabic poetry, which was an integral part of Arabic culture with a long history by the tenth century, uses vowel length in set patterns to establish meter. Dunash adapted this by counting shva na, chatafim, and וּ (probably pronounced as in Arabic, wa) as “short.” All other Hebrew vowels were considered “long.” After this move, Arabic poetic meters could be readily applied to Hebrew. This was, however, a deeply controversial move. Why? Well, for one, it seemed to equate Hebrew with Arabic, which was the crux of the criticism of Menachem’s students against Dunash. Also, soon enough, Arabic poetic meter would be used by Sefardi poets to create liturgical piyut. This is something like, culturally speaking, composing a hiphop Shabbat song, to be sung by the crowd at shul. As in, bound to rankle some.

However, the comparison between Hebrew and Arabic would prove enormously fruitful in the linguistic arena. Around the turn of the millennium, c. 1000, Yehuda Ibn Chayuj wrote two books (among others) devoted to the Hebrew verb, in which he presented the verb as being triliterate or tri-radical: having three consonantal anchors. (There are some linguists who add layers of precision to what is meant by this and the nature of Ibn Chayuj’s innovation.) Yonah Ibn Janach, the student of Menachem’s student, completed Ibn Chayuj’s work, engendering an enduring, bitter debate of his own that spawned a whole bookshelf of responses and counter-responses. But they created the foundations of Hebrew grammar as we know it, their insights lasting centuries. The meanings of words, it turns out, mean a lot.

Reads and Resources

If you want a geeky, wonderfully clear tour through the recondite formality of Hebrew quantitative meter, see Dr. Raymond P. Scheindlin (my teacher)’s information sheet, fourth link (pdf) here.

Many of the classical grammatical works are available in older or critical editions, but they’re specialty pubs. One exception is Machberet Menachem, which is available online here at Daat and here at Sefaria, as well as in the important (though outdated) 1854 edition here on HebrewBooks.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective. If you’d prefer to make a one-time donation in any amount, you can do that easily through my page at Ko-fi. Thank you so much.

The words ben and ibn are cognate; they just mean “son of.” Sometimes, confusingly, Jewish “Ibn” names are no longer patronymics but function as surnames, much like we have them today. R. Avraham Ibn Ezra’s father was not probably not called Ezra; he was from the Ibn Ezra family, to which the poet Moshe Ibn Ezra may have also belonged. Sometimes it’s uncertain whether a person is using a patronymic or a surname, as in, here.

See also the beatiful translation and notes of Dr. Raymond P. Scheinlin, my teacher, in Wine, Women, and Death, 40-45.

Dunash claimed that he was raising 200 objections, but 180 (or 178) are extant.

"This would be like if you could hear the difference between a kamatz gadol (אָ) and a patach (אַ)."

All systems of grammar that are based on the Tiberian system must have an audible difference between a patah and kamatz (the distinction between kamatz gadol and katan is itself a product of the Spanish grammatical tradition). Otherwise they would just be the same thing. The distinctive feature of Spanish grammar in this regard is that the distinction between a patah and a kamatz is identified (solely or primarily) with length. This is quite characteristically Spanish not just because it involves importing classical Arabic grammar into Hebrew, but also because of the imperious assumption that because Spanish Jews treated these vowels as phonemically identical then so must the Tiberian system.

I absolutely love that there was a period in History where people got fired up about grammar! Its fascinating to see how different areas of Torah resonate with different generations. Like a jewel with many facets, the Torah refracts new glimmers of meaning as it is turned in the hands of each age.