Coffee with Ritva

☕Ritva's synthesis brings together Sefarad and Ashkenaz, philosophy and Kabbalah, Rambam and Ramban—all in service of his search for the essence of halachic argument and hidden meanings in Torah.

Hello, dear readers! It’s great to be back with you for another Rishon story. We’re still in the late thirteenth/early fourteenth century period of flux this week; still exploring the lives and works of the inheritors of Ramban’s towering legacy. In Ritva’s contributions, we see a master of synthesis at work: he brings together centuries of scholarship and digs deeply into philosophy and Kabbalah alike.

In this issue:

Ritva’s Sefardi Synthesis

The Chiddushim (“insights”) on the Talmud of R. Yom Tov ben Avraham Ishvili (“of Seville”) are mainstays of the yeshiva curriculum in our own day. Anyone who seeks to navigate the Sea of Talmud will find the Ritva, at least occasionally, as their intrepid guide. And for good reason. With Ritva, you’ll get a clear account of scholarly thought on the sugya (section of Talmud) from the time of the Geonim down to Ritva’s time, as well as his own insights. Included are Sefardim and Ashkenazim alike.

Born c. 1250 into a family hailing from Seville in southern Spain, Ritva made his way north to study in Barcelona under the great Rashba and Ra’ah (R. Aharon ha-Levi). Aragonese archival documents place him in Zaragoza (Saragossa) as a dayan (rabbinical court judge). In this too, Ritva represents a Sefardi synthesis: he knew Arabic, probably nurtured during his early days in the south, but established himself in the north under the tutelage of Christian Iberia’s most prominent Jewish leaders.

Consider the synthetic nature of Ritva’s explanation of the bat kol (heavenly voice) that decrees that both Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai’s interpretations are “the words of the living G-d,” but the halacha is in accord with Beit Hillel:

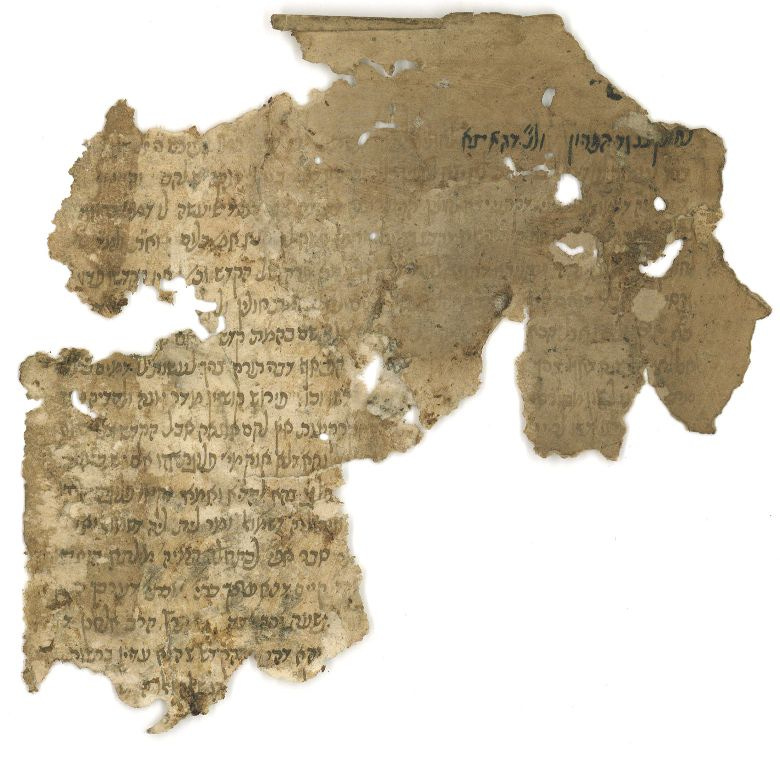

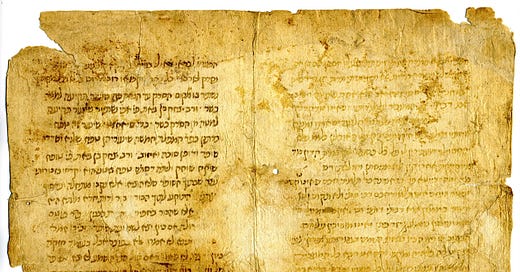

אלו ואלו דברי אלקים חיים שאלו רבני צרפת ז״ל היאך אפשר שיהו אלו ואלו דברי אלקים חים וזה אוסר וזה מתיר ותרצו כי כשעלה משה למרום לקבל התורה הראו לו על כל דבר ודבר מ״ט פנים לאיסור ומ״ט פני׳ להיתר ושאל להקב״ה על זה ואמר שיהא זה מסור לחכמי ישראל שבכל דור ודור ויהיה הכרעה כמותם ונכון הוא לפי הדרש ובדרך האמת יש טעם סוד בדבר.

“These and those are the words of the living G-d”—the rabbis of France, of blessed memory, asked: how is it possible that these and those can be the words of the living G-d, when one forbids and one permits? For when Moshe ascended on high to receive the Torah, it was shown to him, about every matter, forty-nine ways to forbid and forty-nine ways to permit. He asked the Holy One, blessed be He, about this and He said that this is to be given to the sages of Israel that are present in each generation, such that there will be judgement in accordance with them. This is all true according the traditional interpretation (derash), and by way of truth, there is an esoteric reason (ta’am sod) in this matter.

There is so much of Ritva on display in this passage. It’s important to note that most of his Chiddushim deal with the technical aspect of the law, meaning that this is not representative of the kind of sustained argumentation included in his commentary. It is, however, an important moment when he steps back and asks a meta-question, revealing his interest in the theory of the law. He brings in the views of the “rabbis of France,” a typical inclusion of Ashkenazi scholarship amidst his own Sefardi tradition. He answers their question about pluralism by suggesting, following tradition, that each facet of legal reasoning has its place and value in particular times and places. And then, he gives us just a taste of a deeper meaning: it is an esoteric secret.

Rationalist/Kabbalist

An initiate of the Kabbalah of his teachers, Ritva was also well-read in logic and other rationalist philosophy. In fact, he wrote a book, Sefer ha-Zikaron (“The Book of Remembering”), critical of Ramban’s hassagot (criticisms) of Rambam and in defense of the Moreh ha-Nevuchim (“Guide of the Perplexed”). He undertook a careful study of the Moreh, comparing the Hebrew translation with the original Judeo-Arabic. He concluded that Ramban, whom he revered as the master of all Sefarad, did not fully understand the depths of the Moreh. And yet, he insisted that Ramban’s Torah and Rambam’s Torah were coeval: equally valid on different planes of meaning. In the introduction to Sefer ha-Zikaron, he wrote:

עמודי זהב וכסף אשר בית החכמה נכון עליהם…הם המאור הגדול מורה דעה ומבין שמועה, מלא תורה ומצות כרמון, רבינו משה בו מיימון, ואשר החזיק ביסודות התורה ותקעם יתד במקום נאמן האשל הגדול מצדיק הרבים ככוכבים רבי’ משה בר’נחמן.

…[They are] pillars of gold and silver upon which the house of wisdom steadily rests…they are the great luminary, the teacher (moreh) of knowledge and master of tradition, as full with Torah and mitzvot as a pomegranate: Rabbenu Moshe ben Maimon; and he who grasps the foundations of the Torah, anchoring them in a firm location, the great oak who guides those as numerous as the stars: Rabbenu Moshe ben Rabbi Nachman.

Ritva, Sefer ha-Zikaron, Introduction

In addition to his Talmud commentary, halachic works, responsa, and criticism, Ritva wrote a commentary on the Passover Haggadah. In it, he ponders the way G-d is referred to as ha-Makom, “the Place.” Ritva first suggests the answer given in Bereshit Rabba: G-d is the “place” of the world, even as the world is not His place. But then, Ritva, as is his way, gives another, coexistent, deep meaning:

ברוך המקום שנתן תורה לעמו ישראל וכו'. …ויש אומרים כי אמר מקום בענין זה, לפי שעד שלא נתן הקב"ה תורה לישראל לא היה נודע לא הוא ולא חכמתו, אלא כדבר הגנוז במקום נסתר ואינו נראה, וכשנתן תורה לישראל אז הופיע אורו לכל העולם, ועל דרך האמת זה כמו הנה מקום אתי (שמות לג כא), שהוא מקום ההשגה לאספקלריא המאירה מקום תמונת ה', ועל פנים המאירים אמר ברוך הוא, והמבין ידום.

There are those who say that it says “Makom” for this reason, that until the Holy One, blessed be He, gave the Torah to Israel, He was unknown and neither was His wisdom, except as something that is hidden away in a concealed place and cannot be apprehended. When He gave the Torah to Israel, then its light became apparent to the entire universe, and by way of truth, this is like the verse, “there is a place (makom) near Me”(Shemot 33:21), which is a place of reaching the looking-glass (aspaklaria) that radiates1 the place (makom) of the image of Hashem, and it was with regards to the radiant Face that He spoke, may He be blessed, and he who understands will stay silent (ha-mavin yidom).

Today Ritva sits in the company of Sefarad’s greatest Rishonim, his place on the shelves of the beit midrash prominent, himself as full of Torah as a pomegranate and as sturdy an oak who teaches multitudes of students. However, his great Chidushim were largely published in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. His important teshuvot (responsa) had to wait until the twentieth century for publication. This is a powerful reminder not to take for granted that we possess the Ritva's works and can easily consult them. Even the "standards" arrive to us tenuously. But arrive they do: words written in Aragon some seven centuries ago are still alive in our batei midrash.

Ritva Reads

Over on Sefaria, you can access most of Ritva’s Chiddushim, one teshuva, and the Haggadah commentary, although untranslated. (Bava Batra can be found here; fuller responsa, here.) Sefer ha-Zikaron is available on HebrewBooks.org (there are other editions there as well).

It’s a specialist piece, yes, but a great read (promise): Dr. Ephraim Kanarfogel’s “Between Ashkenaz and Sefarad: Tosafist Teachings in the Talmudic Commentaries of Ritva.”

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

Have I ever mentioned I had a stint in art school back in the day? I retain a deep love for the visual arts and a wide-ranging side interest in Jewish art. (See: my Pinterest.) It’s been under construction, now reconstruction, for a long while, and is a bit clunky to navigate, but I still love the Center for Jewish Art website, a project of Hebrew University. It covers ancient to modern art, including ancient art, synagogue architecture, illuminated manuscripts, modern painting, and more.

Ritva on Twitter

ICYMI!

Next Coffee Date

You’re in for a treat—he’s one of my absolute favorites: R. Menachem ha-Meiri. (But, you know, they’re all my favorite.)

See Sanhedrin 97b. “Looking through an aspaklaria ha-meira” is a commonly-used epithet for achieving mystical understanding in medieval Kabbalah.

"He brings in the views of the “rabbis of France,” a typical inclusion of Ashkenazi scholarship amidst his own Sefardi tradition. He answers their question about pluralism by suggesting, following tradition, that each facet of legal reasoning has its place and value in particular times and places."

Unless I am mistaken, both the question and answer in the passage are from חכמי צרפת, hence "שאלו רבני צרפת ז״ל ... ותרצו". Perhaps there are cases of Ritva providing an answer to a open question from Ba'alei Tosefos, but this does not seem to be one of them.