Coffee with the Ran

☕A fruitful era of synthetic Sefardi scholarship reaches its conclusion in the work of the Ran; his students took his Torah with them in addressing the unforeseeable difficulties of their day.

Hello, dear readers. And I do mean that: this newsletter continues to grow, thanks to you, and each signup is dear to me. You’re my people.

Today we’re exploring the calamitous fourteenth century through the life of R. Nissim ben Reuven Gerondi, better known as the Ran, who was born around 1305 (or slightly later, in the 1310s) and died around 1375. The fourteenth century gets this moniker from Barbara Tuchman, an interesting figure in her own right. Academic historians are generally disdainful of non-guild-members like Tuchman, and there’s valid reasons for that. However, Tuchman had the deck stacked squarely against her—specifically, against her accessing the training of a professional historian—but still managed to bring history to life, if imperfectly, for many. Though her medieval book is, like so much history writing, more about her own time, the twentieth century, than the one she was purportedly writing about, “calamitous” is an achingly fitting descriptor for the fourteenth century.

Okay, you might be thinking, it’s not like the thirteenth century, where we’ve spent quite a lot of time recently, was exactly uneventful. There was the whole seismic shift in Christian attitudes towards Jews, which led to disputations, conversionary efforts, and book burnings. There were blood libels, the first general, or kingdom-wide, expulsion of Jews (from England, in 1290), and the horrific Rindfleisch massacres that impelled Rosh to flee Germany. What makes the fourteenth century different, I’d say, is the degree of dissolution that occurs among the Jews of Europe.

The Black Death arrives on European shores in 1348 and ravages the continent over the next year, resulting in waves of anti-Jewish violence: Jews were blamed for poisoning wells and otherwise being responsible for the plague. By 1400, Jews have largely been emptied out of Western Europe, their rights of settlement rescinded by royals desperate to raise funds for their armies. In Spain, nearly half of the largest Jewish community in Europe has been converted to Christianity through coercion, terror, and/or ecstatic, populist missionizing. Not to mention the brutal Hundred Years’ War, populist uprisings, and a papal schism causing instability among Christian rulers. It is this world that Ran and his students finds themselves facing.

In this issue:

Back in Barcelona

The Ran garners the appellation “Gerondi,” of Girona, his family’s hometown, probably en route from Córdoba. He himself was active in Barcelona where he headed the famed yeshiva. He worked in the tradition of the Ramban as continued by Rashba, Rah (R. Aharon ha-Levi of Barcelona), and Ritva. The Ran’s lucid capacity for capturing the insights of this fruitful school render his halachic works a sort of culmination. Despite the fact that he did not hold an official position such as dayan (rabbinical court judge), the Ran became the leading decisor of Aragon (northeastern Spain) and was widely consulted beyond its borders as well.

The Ran’s life was not particularly placid; he not only lived through the Black Death and witnessed an influx of Jewish exiles from France, but was also arrested (for reasons that are not entirely clear) and spent several months imprisoned on trumped-up charges. However, he died prior to the great upheavals that would strike Aragon and then Castile in 1391-92. It was left to his students to lead, adjudicate, and grapple with these events, which they did by drawing upon both Ran’s halachic and ethical writings. The Ran’s leading students included the Rivash (R. Yitzchak bar Sheshet Perfet), whose responsa include many important rulings dealing with Conversos; the Nimukei Yosef (R. Yosef Chaviva), who wrote Chiddushim on Shas and a commentary on Rif, like his teacher; and two figures who developed the Ran’s complex anti-philosophical philosophy, which we’ll explore below: R. Avraham ha-Levi Tamach and the late, great philosopher-polemicist R. Chasdai Crescas.

The Ran on the Rif

Like his predecessors, the Ran wrote in multiple genres of halachic literature. He produced Chiddushim (“insights”) on the Talmud, probably from his teaching notes for those tractates that were studied in the Barcelona yeshiva. He also wrote commentaries on several masechtot (tractates), most notably on Nedarim, where his commentary appears in the usual place of the Tosafot in standard editions of the Talmud, opposite pseudo-Rashi—the commentary attributed to Rashi but probably composed in the Rhineland by German scholar(s). In these writings, the Ran is conceptually oriented, discussing major themes and problems that arise in the sugya. He selects judiciously from a wide array of commentary, from the Geonim to his predecessors.

The Ran is most noted for his commentary on the Rif, in which he not only deals abstractly with halachic subjects but resolves them with a decision. In some cases, the Ran’s view shapes subsequent discussion—such is his stature as a decisor. His commentary is, in that sense, broader than the Rif, with the Rif’s “Talmud Katan” providing a structure for the Ran’s positions.

The (A?) Twilight of Jewish Philosophy

The two great medieval systems of meaning developed to speak to the purpose of Jewish law and practice were rationalist philosophy and Kabbalah. As the Middle Ages draw to a close, we see that philosophy falls away and Kabbalah gains ascendency. The Ran, though not a Kabbalist (and, some have argued, was even opposed to Kabbalah), belongs to this era of eclipse. While he was familiar with the conceptual world of late medieval philosophy, the Ran has a noted anti-philosophical trend in his writing, which he bequeathed to his famed student, R. Chasdai Crescas. Despite attaining renown as a philosopher, R. Chasdai became a principled critic of Aristotelianism.

Let’s take a close look at one of Ran’s Derashot to see how his anti-philosophical philosophical streak works. His long first derasha deals with the iconic early stories of Sefer Bereshit (Genesis), beginning with creation itself. How, asks Ran, can we square the goodness of creation with Kohelet’s pessimism?

והנה זה כלו אף על פי שאימת אותו טבע ההויה ונמשכו עליו דברי רז״ל יראה זר מאד בעיון בהפך ממה שנבנה עליו ספר קהלת, כי הוא פסק הדין בתחלת ספרו היות כל הנמצאים שתחת הירח הבל ובלתי בעלי קיום והעמדה, ואחר גזרתו זאת הוכיח אותו בראיות והכלל שעליו סובבות ראיותיו כלם הוא שאחר שהמורכבים האלה הורכבו מפשוטים שהם בעלי תנועה ושינוי שהוא מהמחוייב שהמורכבים מהם יהיו באותה תכונה עצמה

But all of this [goodness], though it be confirmed by nature and substantiated by the words of our sages of blessed memory, seems exceedingly strange upon closer scrutiny, at complete variance with the premise of the Book of Ecclesiastes, in the beginning of which it is laid down that all things beneath the moon are vain and ephemeral, this assertion being subsequently borne out by proofs, the principle upon which they all revolve being that since these composites were all compounded from elements that are subject to movement and change, it must necessarily follow that the composites themselves partake of these characteristics.

This language of “elements,” “composites,” “movement,” and “change,” is drawn from Greco-Islamic philosophy (including natural philosophy, which would become the thing we call “science”). It indicates that the Ran was no stranger to the pervasive intellectual culture of his times. Consider, however, the focus of Ran’s interest in understanding the meaning of the Mikra (Bible) and on its ethical significance (emphasis added):

וזה היה ענין דור הפלגה ועונשם שהניחו אותנו המפרשים באפלה עד שכמעט נגששה כעורים קיר, כי אלו האנשים מה עשו מה פשעם ומה חטאתם אם רצו להיות כאיש אחד חברים, הלא היה ראוי להיות להם בזה שכר טוב, כי ראינו הכתובים כלם מישרים אל זה הדרך עד שאמרו אפילו עובדי ע״ז כל זמן שהשלום ביניהם אין מדת הדין פתוחה כנגדם, והסמיכו זה אל הפסוק חבור עצבים אפרים הנח לו. ועם היות שבאו בטעם ענשם של אלו מדרשים, אינם מסכימים לפשוטו של מקרא, כי לדברי מי שאמר שהיתה הסכמתם לעלות לרקיע, הוא מן התימה איך הסכימו כל בני עולם בשטות כזה, ולו חשכו ראותם ועורו עיני שכלם היה ראוי להיות פתיותם מציל אותם מן העונש, וכיוצא בזה יישב בשמים ישחק וכו', ועוד כי לו פשטו יד בעיקר איך תספיק ענשם להפיץ אותם לבד, ועוד כי מפשט הפרשה נראה כי לא היה עונשם על מה שעשו כבר אבל מה שהיה אפשר שימשך ממעשיהם… וכל אלה הדברים משימים המשכיל במבוכה וצריכים ביאור, וכל זה נמשך ונוסד על השורש שאמרנו, כי חברת הרשעים ואסיפתם דבר מזיק, הן בעת השתדלם בפעולת רעתם, או לא ישתדלו בה, כאשר חברת הטובים דבר מועיל, הן בעת השתדלותם, או בעת ינוחו

And this is the principle behind the generation of the dispersal [dor hapalagah] and their punishment, concerning which the expositors have left us so much in the dark that we are almost like the blind groping for the wall. For what did these people do? What is their offense and what is their sin? If they wished to form a common bond, should they not merit a goodly reward for their labors? For we see all of Scripture directing us in this path, so much so that our sages have declared (Sifrei 42): "Even idolators, so long as there is peace among them, the attribute of justice is not stretched out against them," basing this upon the verse (Hosea 4:17): "Ephraim is joined [in unison] to idolatry — let him alone." And though there are midrashim dealing with the reasons for their being punished, they do not accord with the plain meaning of the verses. For according to the view (Genesis Rabbah 38) that they made a compact to ascend to the heavens, this is indeed to be wondered at. How could all of humanity concur in such folly? And if their sight was withheld and the eyes of their intellect blinded, then their ignorance itself should have protected them from punishment, it being written about such as these (Psalms 2:4): "He who sits in heaven will laugh; the L-rd will mock them." What is more, the plain meaning would indicate that they were being punished not for what they had already done but for the potential repercussions of their deeds… All of this places the thinker in perplexity and demands explanation. [The explanation is as follows.] All of this proceeds from and is founded upon the above-stated principle: the company of the wicked and their gathering is injurious, whether they are actively engaged in the performance of evil or not, just as the company of the good is beneficial, whether they are actively engaged in the doing of good or not.

Here we see the Ran’s synthetic approach on full display. He is, on the one hand, steeped in knowledge of midrash, to which he accords much attention and great authority. At the same time, he is unflinching in his insistence that peshat (contexual or “straightforward” readings) must not be ignored or abrogated. In this Ran echoes Ramban’s sense of multiple, coexistent layers of meaning. However, Ran’s interest coheres in the ethical meaning borne by the narrative: What does it mean for us that the generation of the Tower of Babel was dispersed? As we’ve seen, he builds upon rationalist habits of mind to draw his conclusions, a theory of collative forces. But Ran grounds logic in prooftexts from Tanach, ultimately rejecting philosophy for an ethical-homiletic take-home point, namely, forces of evil bind together collectively, but so too do forces for good.

Ran Reads & A Listen

The Ran’s Derashot are available on Sefaria along with a good English translation by R. Shraga Silverstein and on Al HaTorah. Ran on the Rif is available on Sefaria and Al HaTorah (search by masechet); the latter has a fuller selection of his Chiddushim.

Seforim Chatter has a podcast devoted to the Ran’s Derashot.

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

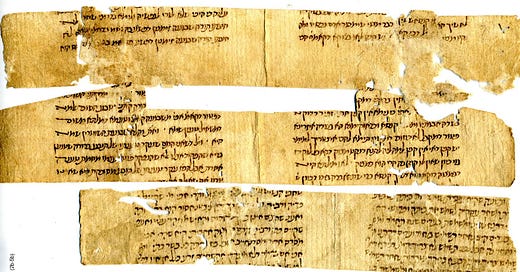

If you’re learning Talmud, you’re bound to encounter interesting and potentially substantive differences in girsa (versions of the text). The Friedberg Jewish Manuscript Society has an amazing tool called Hachi Garsinan that allows you to quickly compare the Vilna (standard) text of the Bavli against major textual witnesses (important printings and manuscripts). It requires a free and painless registration with an email address in order to use it. I wrote a quick-start guide to using Hachi Garsinan which you can find here.

Ran on Twitter

Next Coffee Date

Next time we’re going to be with R. Yitzchak Abravanel, who will take us into the fifteenth century and along with him as he flees the order of expulsion from Spain.