Important Manuscripts of the Mishnah and Tosefta

📜 Our major textual witnesses to the text of the Mishnah show slight, but occasionally enlightening, differences that can be examined with reference to the manuscripts.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. Last week, we looked at Masoretic codices, or bound Hebrew Bibles with Masoretic notes, including nikud (vowel marks); today, we’re turning our attention to the text of the Tannaitic Mishnah and Tosefta. A special thank you to readers of my Sunday Twitter thread, who contributed their expertise, insights, and questions that helped shape this edition! (If you’d like to read the thread, it’s here. No Twitter account required.)

Audio: Listen to this Newsletter (paid feature)

Subscribers can find the audio for this post here, read by me. You can always click on the “Podcast” tab as well.

In this issue:

There is something astounding about coming to know that the texts we take for granted, that we tend to see as stable and fixed, have a history of being handed down that is intimately connected to the lives of individual humans. We often don’t have so much information to color our understanding of these individuals (as will, alas, be the case today), but their handwriting serves as testimony to their presence and efforts. In most cases, the textual histories of even foundational texts hangs on a thread, resting on a small number of textual witness. (Textual witnesses are just what they sound like: manuscripts that serve as early evidence for the modern printed texts, or postmodern digital texts, that we see before us.) There are, of course, plentiful manuscripts as a whole of such texts, but most are copies of each other (or of similar texts, no longer extant). In other words, there are few early exemplars that serve as “witnesses” to the version of the text coming out of antiquity, often, as for the Mishnah and Tosefta, out of orality and into textuality.

Variations in the Text of the Mishnah

It bears emphasizing at the outset that textual variations in the received text we have of the Mishnah are slight. For the most part, they are of interest to historians trying to reconstruct the processes that affected the transmission of the text more so than to Torah scholars, for whom there is rarely a substantive difference in meaning. That being said, there are occasional differences in phrasing (the way a Mishnah is divided up) or in wording that do potentially change the meaning of the text. For such cases, it can be illuminating to look at a critical edition, which marks the differences among major manuscripts, or at the manuscripts themselves. (Yes, even non-experts! See my quick-start guide to using Jewish manuscripts; for critical editions, see below in the resources section.)

Differences in versions of the Mishnah were noted already by the Amoraim and later by the Rishonim, especially Tosafot (dialectical commentary to the Talmud produced in Ashkenaz). One such comment appears in the Tosafot to Bechorot 22b, which examines the text of the Mishnah under discussion. The context of the Mishnah, which isn’t so important for our topic, is a mix-up of consecrated foodstuffs that are due to the kohanim (priests) and non-consecrated foodstuffs. What should be done in such a case of doubt—does the entire lot of food need to be discarded, and if so, how? According to the Mishnaic sage Rabbi Eliezer, a seah measure should be “removed” from the lot (terom). In the text of the Mishnah that appears in the Bavli, the next word is “and left to rot” (tirakev). However, in the Mishnah text as it appears in the Yerushalmi, the next word is “and burnt” (tisaref). So which one is it? Left to rot, or burnt? Here is what the Tosafot say:

מת’ [תרומות ה ב] רבי אליעזר אומר תירום ותרקב

תירום ותירקב - בירושלמי תני תשרף וקשה…ור"ת מפרש דתרקב ותשרף הכל אחד והגמרא שלנו מפרש ותשרף דתנן היינו בלא הנאה כעין רקבון דאי שרית בהנאה אתי למיכליה הואיל וסברא היה להתירה ע"י בטול כדאמרי רבנן תעלה ותיאכל כו' וה"ק או תרקב או תשרף בלא הנאה ועוד יש לפרש דמחלוקת של בני בבל ושל בני א"י מהש"ס שלנו והש"ס ירושלמי וכמו כן בבבא אחרת ששנה באותו פרק דקתני אחר שהודו ר' אליעזר אומר תירום ותישרף קתני בתוספתא תירום ותרקב ואפשר דאיכא תני הכי ואיכא תני הכי וכן נמי אשכחן בפרק מצות חליצה (יבמות דף קד:)…

Mishnah [Terumot 5:2]: Rabbi Eliezer says: [a seah] must be removed and left to rot…

“Removed and left to rot” - In the Yerushalmi it is taught and burnt. This raises a difficulty… Rabbenu Tam explains that left to rot and burnt are one and the same matter. Our Gemara explains that the meaning is burnt, as it is taught: meaning, without benefit, as a kind of rotting away. For if it was permitted to benefit from it, one might come to eat it [the consecrated foodstuff], reasoning that it would be permitted were it to be nullified, as the Tannaim stated, “It may be taken out and eaten,” and so on. Thus whether it says to rot or burnt, it must be without benefit. We also need to explain this as a disagreement between the Jews of Babylonia and the the Jews of Eretz Yisrael, between our Talmud and the Talmud Yerushalmi. In addition, in another section that is expounded in the same chapter, it is taught, after they agreed that Rabbi Eliezer said must be removed and burnt, they taught in the Tosefta [that he said] must be removed and left to rot. It is possible that one taught thus and the other taught thus, and indeed this is what we find in the chapter called “Mitzvat Chalitza” [Chapter 12 of Yevamot, on amud 104b].

The Tosafot here compare three parallel versions of the text, from the Bavli, the Yerushalmi, and the Tosefta. Notice that they first attempt to harmonize the significance of “left to rot” and “burnt,” but conclude that it may simply be a difference in versions. This, they note, is a possibly raised explicitly elsewhere in the Mishnah, in a different context. Centuries19th ago, such small differences were recognized and discussed, especially between the version of the Mishnah preserved within the Talmud Bavli as opposed to the Yerushalmi.

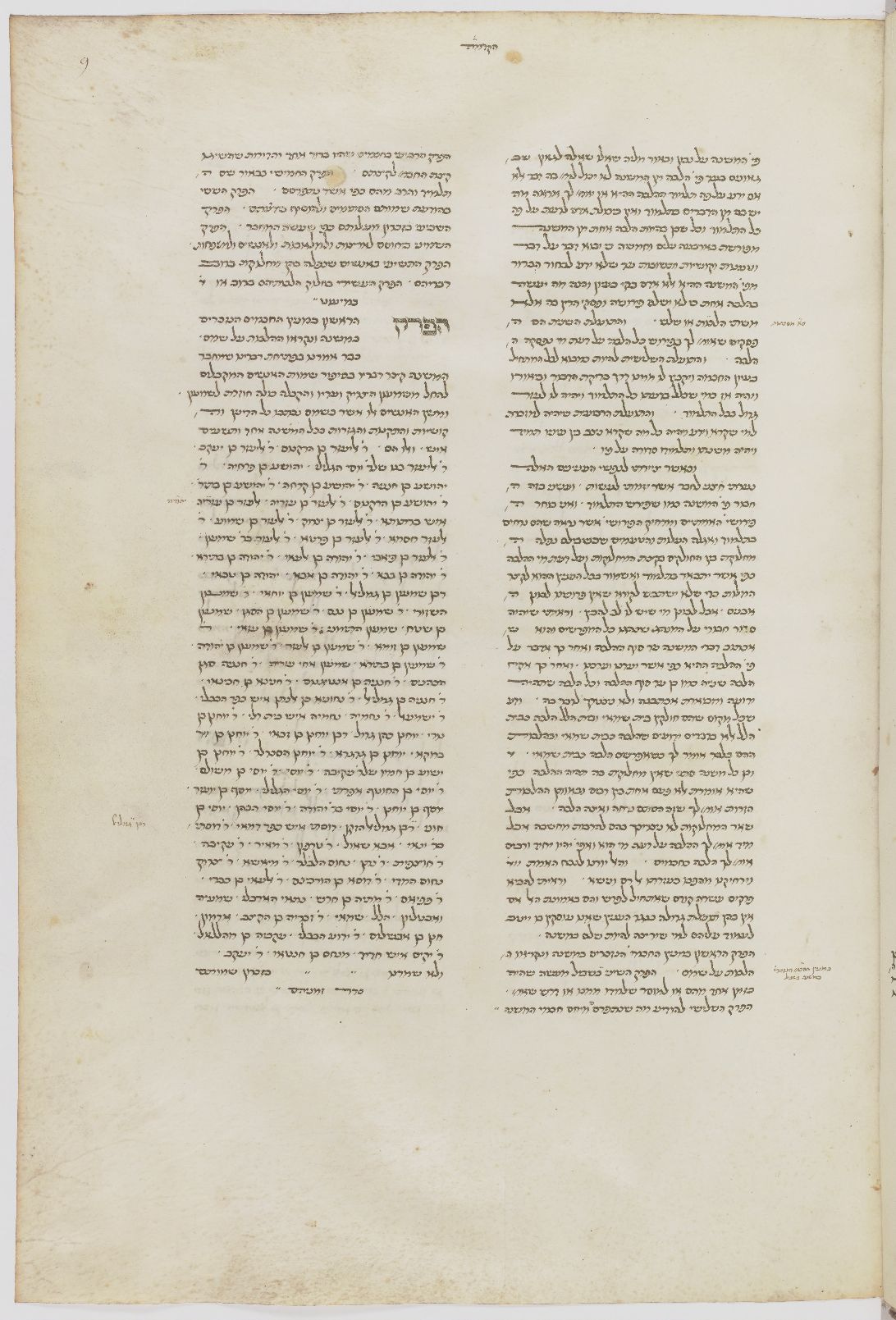

The King of Mishnah Manuscripts: Kaufmann

Our greatest exemplar for the Mishnah is the Kaufmann manuscript, pictured in the first image above (Ms. Kaufmann A 50, now at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest; it gets its name from its previous collector, the erudite and prolific 19th-century Jewish scholar David Kaufmann). Initially thought to date from the 13th century, it is today dated earlier, 11th-12th century, with its Tiberian vocalization added somewhat later. It is written in an Italian script and bears marked similarities to the Mishnah as recorded in the Yerushalmi, i.e., the Eretz-Yisrael version.

Several of the famous manuscripts from the erstwhile Kaufmann collection have a dedicated website, which features full-color images. Another, quite handy way to consult Kaufmann is to use the Sefaria interface. While browsing the Mishnah, look for “Manuscripts” in the tools sidebar (mine is in Hebrew, but it should appear in the same place in the English interface):

Click on “Manuscripts” and you’ll see the available images right in the sidebar. In this case, there’s just the one, Kaufmann. Click on the thumbnail and you’ll see a high-res image keyed to the page you’re in (which is, like, a manuscript miracle):

Other Important Mishnah Manuscripts: Parma, Cambridge, Paris, and More

There are two more manuscripts of the Mishnah that are substantially complete. Of great importance is “Parma” (Palatina Library, Parma, Italy Cod. Parm. 3173, formerly known as de Rossi 138). It is potentially earlier than Kaufmann, dating to the 11th century. Also written in an Italian hand, and with partial vocalization added later, it can be browsed at the link above. Some scholarship has argued that Parma formed the basis of the text in later manuscripts, specifically the Leiden manuscript of the Talmud, which we’ll get to in a minute (but cover in depth next week).

Also significant is “Cambridge” (Cambridge University Library, Ms. Add. 470, 1), a later manuscript dating from c. 1400, likely from southern Italy. The hand is variously described as semicursive Byzantine (southern Italy having been under the cultural and sometimes political sway of the Byzantine empire for centuries) or “Sefardic-Greek.” This piques my curiosity, because we see here what appears to be an Italian tradition of preserving the Mishnah text on its own, and, later, the revival of Mishnah study in Italy in early modernity. But, tzarich iyun—it requires further inquiry. You can browse Cambridge here.

It should be noted that important texts of the Mishnah are also found within the “star” manuscripts of the Talmud Bavli (“Munich”) and the Yerushalmi (“Leiden”). That is, in these manuscripts, as in our contemporary versions of the Talmud, the Mishnah and Gemara are both contained in the body of the text. These are another “first place to look” for Mishnah textual variants, but we’ll cover the particulars of these two manuscripts next week, when we turn to Talmud manuscripts.

The manuscript known as “Paris” (Bibliothèque nationale de France Ms. hebr. 328) includes a text of the Mishnah along with Rambam’s Mishnah Commentary in Hebrew translation. It too was written in an Italian hand, c. 1400. Similarly, Rambam’s own copy of the Mishnah Commentary (in Judeo-Arabic)—possibly an autograph copy (meaning written by Rambam himself)—contains a text of the Mishnah. As sometimes happens, the original manuscript was later split into pieces, with two ending up at Oxford University’s Bodleian Library (Mss. Hunt. 117 and Poc. 295) and two in the Sassoon collection (yes, the same one from which the “Sassoon Codex” of the Masoretic Bible came), later united the National Library of Israel as Ms. Heb. 4°5703. This makes it a bit tricky to consult, but it’s good to know about (and shows us the version of the Mishnah Rambam had before him!)

A final major source of variant readings of the Mishnah is the fragmentary evidence from the Cairo geniza.

The Major Tosefta Manuscripts

There are three manuscripts of the Tosefta of great significance because of their age and state of preservation. The reigning champ is known as the Vienna manuscript (or “Vienna 20”), because it’s owned by the Austrian National Library in Vienna (Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek Cod. hebr. 20). This manuscript, despite some losses over the years, is close to complete. Its script is Sefardic. Though script tells us more about the training and potential identity of the scribe and not necessarily about provenance (where the manuscript was physically created), this is an important detail.

The Erfurt manuscript, formerly owned by the Library of the Evangelical Ministry in Erfurt, Germany, and today housed in the State Library of Berlin (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin), Ms. Or. fol. 1220), is at least a century, possibly two, older than the Vienna manuscript, dating from the 11th or 12th century. However, it contains only four Sedarim (Orders) of the Tosefta. Erfurt is written in Ashkenazic script, and it’s been suggested that its text reflects a version of the Tosefta circulating in Ashkenaz.

Finally, the London manuscript (British Library Ms. Add. 27296), produced in the 15th century and written in a Sefardic hand, contains Seder Moed (on the holidays) and Chullin (on kosher slaughter). Though considered less textually reliable, possibly an attempt to harmonize earlier versions, it is a contender for the text that informed the publisher of the first print edition, produced in Venice in 1521-22 as an addendum to the Rif. (That edition is based on a lost manuscript, but possibly from the same family as the London manuscript.)

Mishnah Reads & Resources

This time I included most of the resources above in the body of the newsletter, but a few more recs:

This recent book called What Is the Mishnah?: The State of the Question, edited by Shaye J. D. Cohen, is high on my reading list. You can read Shamma Friedman’s chapter, “Mishnah and Tosefta,” here.

Here’s a handy list of Critical editions of the Mishnah at the Talmud Blog. Fair warning: they are going to require a lot of legwork to track down, and likely access to a well-stocked library. However, good to know about in case you get into the weeds and intensely curious about a particular Mishnah. (You know?)

For Hebrew readers, check out this comparison tool for the Mishnah at NLI that displays multiple manuscript thumbnails for each Mishnah. (Thanks so much to the reader who alerted me to this amazing resource!)

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective.