New Genres of Geonic Creativity

🕍 The Geonim of Babylonia created important new genres of writing which profoundly influenced, the Rishonim, including the Sheiltot, the early halachic codes, the first siddurim, and more.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. We continue in the Geonim series with an issue devoted to the wonderfully creative genres invented by the Geonim to express their learning and insights.

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here (and an archive of all audio editions here.)

In this issue:

The Geonim saw themselves as distinct from their predecessors, having inherited a largely closed text of the Talmud. They were no longer possessed of the authority to substantively add to or change the text created by the Amoraim and redacted by the Savoraim. This meant that they developed new ways of writing and disseminating halacha and Torah thought. These were not yet the type of Talmud commentary that would characterize the writing of the Rishonim,1 who followed the Geonim. Rather, they were foundational genres that were influential upon and further developed by the Rishonim. We’ll explore these below.

The Responsum (Teshuva)

The rabbinic teshuva remains such a basic source of Jewish law, down to our own day, that it is difficult to think of it as an innovation, or as belonging to any given era. In fact, as Robert Brody points out, there is evidence in the Talmud text itself of letters being dispatched to rabbis, who responded to the queries in writing. As such responsa are not entirely an invention of the Geonim. However, their development as an authoritative source of case law and distinctive form of written expression is very much the work of the Geonic period. If the responsum seems ubiquitous, that’s a mark of its pervasive influence from the era of the Geonim forward.

Queries, mostly about practical applications of halacha but also about interpretive issues arising from the text, reached the Geonim from across the Jewish world, particularly after the Muslim conquests and even more so after the establishment of the Abbasid caliphate in the mid-eighth century, which was headquartered in Babylonia (Iraq). Thousands of their responses have been preserved, with many more turning up in the Cairo geniza, often difficult to attribute. We’ve seen how the process of responding to the queries was institutionalized in the yeshivot of Bavel and a core part of the process of the Kallah (convocation) months, according to R. Natan ha-Bavli’s account.

The Sheiltot

A sheilta is a distinctively eastern (as in east of Eretz Yisrael) form of a derasha (sermon or homily). The Sheiltot, associated with one Rav Achai, are a collection of such derashot. Of Rav Achai we know relatively little, although in Rav Sherira Gaon’s letter, he’s presented as a well-known figure. He lived in the mid-eighth century and seems to have been passed over for the gaonate of Pumbedita, whereupon he left Bavel and went to Eretz Yisrael. In any case, the large amount of material and its varying language points to Rav Achai as the compiler or anthologizer of the work.

The Sheiltot include derashot for each of the Torah readings according to the Babylonian cycle, often multiple sermons for each. Their format is fascinating, especially in its focus on halachic material and copious quotation from the Talmud Bavli. It is built in four parts, each of which opens with a formulaic phrase. The question (sheilta) which opens the derasha is about one of the mitzvot (commandments), either positive or negative, generally originating in the the Torah but sometimes also rabbinic. This first section connects in some way to the parsha (the section of the Torah being read that day) and lays out a number of sources pertaining to the commandment at hand. The second section presents a halachic question about the commandment. The third, which forms the “heart” of the sermon, is thematic rather than halachic, presenting an exposition of the meaning of the commandment. The fourth and final section concludes by summarily resolving the question asked in the beginning.

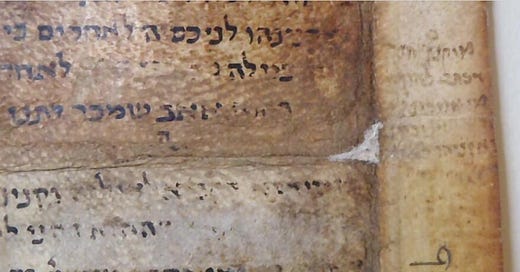

The First Halachic Codes: Halachot Pesukot and Halachot Gedolot

Of enormous importance are the creation of the first halachic codes. These were a natural outgrowth of the Geonim’s self-understanding as interpreters of the Gemara: since the dialectical give-and-take of the Talmud was “closed,” they had to invent new ways to explicate the text. The way they did so was by reorganizing and summarizing the material scattered throughout the Talmudic corpus into easier-to-digest codes. Halachot Pesukot (Decided Laws)’s achievement is reflected in the name by which it’s known: it laid out currently relevent areas of the law as they should be practically followed, including laws of prayer, of Shabbat and holidays, family law, and commercial law. In many respects, it is still beholden to the internal structure of the Talmud, often following it carefully. Still, Halachot Pesukot sets out new subject areas and often synthesizes information from different sections of Talmud. By the time of the Rishonim, Halachot Pesukot was associated with the famed Gaon Rav Yehudai.2

Halachot Gedolot, which superceded Halachot Pesukot even as it was indebted to it, was a groundbreaking work. It is associated with one R. Shimon Kayara, also called Behag (Baal Halachot Gedolot). So called because of its large size, Halachot Gedolot includes not only halachic material but much homiletical material as well, including much drawn from the Sheiltot. It also consciously covers areas of the law not directly relevant in its own time, including the laws of Beit ha-Mikdash (the no-longer-extant Jerusalem Temple). In addition, Halachot Gedolot introduces the introduction: it has a programmatic opening consisting of a conceptual homily on the authority of the Oral Torah. This introduction includes a classified enumeration of the 613 mitzvot, which would later draw the ire of Rambam in his own enumeration, much influenced, however, by the Halachot Gedolot.

The First Prayerbooks

Rav Natronai, who was gaon of the Sura yeshiva in the mid-ninth century, received a query from Lucena, Spain, about the baraita in Menachot 43b which cites Rabbi Meir as maintaining that one is obligated to recite one hundred blessings a day. The questioner asked what, exactly, those blessings are? Rav Natronai Gaon responded with a schematic of the daily prayers and a list of the blessings, which we might call a “proto-Siddur",” or a prayerbook in embryonic form. Rav Amram ben Sheshna, who styled himself gaon of a breakaway yeshiva from Sura, nonetheless mentions his rival’s achievement in the introduction to his far more complete Seder, which encompassed the weekday and Shabbat prayers as well as prayers for the cycle of holidays, including a Pesach Haggada. Seder Rav Amram thus became the first complete enumeration of Jewish liturgy; it also included relevant laws, as most machzorim would continue to do into the Middle Ages. (The exemplary liturgical scholar Daniel Goldschmidt produced a critical edition of this complex text, published by Mosad ha-Rav Kook in 1971.) The importance of Seder Amram Gaon is expressed in a teshuva written by Rabbenu Tam:

Anyone who is not proficient in Seder Ram Amram and in Halachot Gedolot…does not have the prerogative to overturn the words of our predecessors and their practices, for they are to be relied upon for matters that do not contravene our Talmud but only add to it. Many of the practices that have come down to us [literally: that are in our hands] originate with them.

כל שאינו בקי בסדר רב עמרם ובהלכות גדולות…אין לו להרוס דברי הקדמונים ומנהגם, כי יש עליהם לסמוך בדברים שאינם מכחישין תלמוד שלנו אלא שמוסיפין. והרבה מנהגים בידנו על פיהם.]

Rabbenu Tam, teshuva written to R. Meshullam ben Natan of Melun, in Sefer ha-Yashar (responsa section), no. 45.

The idiosyncratic Rav Saadia Gaon also produced an important Siddur.

Halachic Monographs

Speaking of Rav Saadia, who was the initiator of a number of new genres of writing, one his innovations which was subsequently picked up by his immediate successors in the gaonate is the halachic monograph. The fancy term “monograph” refers to an interesting phenomenon: that of the single author. While works like Halachot Pesukot and Halachot Gedolot were, as we’ve seen, associated with an individual, that person served as a compiler more so than an author, and the finished composition was the work of many hands. In contrast, in the later Geonic period individuals begin composing works on discrete topics in halacha, such as the laws of testimony or the laws of business partnerships. These focused works were more synthetic than earlier works, moving outside of the framework of the Talmudic discussion as well as its style in order to synthesize legal information. Some such works dealt, instead, with halachic methodology: the method behind the Talmudic argument and the process of deciding halacha. Both of these areas of subject matter, as well as the genre as a whole, would be much developed by the Rishonim in the coming years.

Reads & Resources

Most of the major primary sources mentioned above can now be found online:

The Sheiltot: Al HaTorah | Sefaria

Halachot Gedolot (Behag): Al HaTorah | Sefaria

Seder Rav Amram Gaon: If you don’t have access to Dr. Goldschmidt’s edition, the Warsaw 1865 is here - Part 1 | Part 2

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective. If you’d prefer to make a one-time donation in any amount, you can do that easily through my page at Ko-fi. Thank you so much.

Although we arguably see what might be called early Talmud commentary in the later Geonic period.

Geonic sources speak of a Halachot of Rav Yehudai, which is generally taken to refer to Halachot Pesukot.

Fascinating stuff.

I love when I am forced to think about things that I previously took for granted and never considered their origins.

The links to Hebrew books dot org don’t work