Coffee with Maharam of Rothenburg

☕Maharam was a rabbi of rabbis, a pietist and Tosafist, the towering authority of all Ashkenazi—who witnessed the Disputation of Paris, endured royal power struggles, and kept writing through it all.

Welcome back to Medieval Ashkenaz, where we’ve spent the last few weeks getting to know to leading lights of the learning revolution started by Rashi. We’ll soon head to the Judeo-Arabic sphere to see how Rabbenu Chananel and Rif spearheaded the learning tradition that would guide Torah knowledge in the Sefardi world.

As a reminder, this kickoff (“Coffee with”) series of the newsletter explores the lives and works of major Rishonim. I have all the greats planned, which should take us up about to Pesach (IY”H). Don’t worry, we’re still going to be hanging with Rishonim on the regular after that, but I have some fun themed series planned, starting with famous Hebrew manuscripts.

In this issue:

Maharam is Too Busy for Coffee

R. Meir ben Baruch (Maharam), whose long life spanned the thirteenth century (c. 1215–1293), lived a life absolutely jam-packed with intellectual, political, and personal triumphs and tribulations. He was the scion of a family remarkably peopled by rabbis, superlative even among Ashkenazi scholarly families, but soon bested them all as the recognized authority of Ashkenaz writ large. By the age of twelve, reputedly, he was sitting in the beit midrash of the Or Zarua. By the time he set up shop in Rothenburg, he’d imbibed the Torah of Tosafists and Hasidei Ashkenaz (German pietsists) alike, sat in the crowd at R. Yechiel’s public disputation with the notorious apostate Nicholas Donin, and witnessed the public burning of the Talmud in Paris in 1242. Despite his dazzling rise to the very top of Ashkenazi society and his flourishing yeshiva, which nurtured a whole generation of rabbis, increasing oppression led Maharam to leave Germany.

He got as far as Lombardy in northern Italy before his plans were disrupted. A formerly Jewish convert to Christianity recognized Maharam and informed the local count that the Jew émigré he had in his jurisdiction happened to be the most important rabbi in all the land. Maharam was arrested and sent off to King Rudolph I.1 He was imprisoned for the remainder of his life. The year was 1286; Maharam was about seventy years old. He wrote stunning works of scholarship from prison.

Posek and Poet

Maharam wrote hundreds of responsa that reached across Jewish Europe. This was often to his consternation—he didn’t like to make non-local rulings on matters of taxation and governance, about which he was frequently consulted. He often dispensed with niceties (with a pro forma apology) and was wont to snap that he’d already answered a given question, sheesh. Many of his ritual rulings are familiar to us today, such as his decision that Rosh ha-Shana is two separate days and not one long day. He thus ruled that Shehechiyanu should be recited both nights—but preferably on a new fruit or garment. Because of the type of rulings that he was called to make in matters of civil law and interaction with the government, his halachic decisions form a major source of Jewish political philosophy.

Maharam was also a skilled poet. His best-known piyut is a pouring-out of anguish at witnessing the burning of the Talmud. The kinah (dirge), שאלי שרופה באש,is recited in most Ashkenazi rites on Tisha be-Av to this day. With typical Maharam panache, the poem spans Jewish cultural spheres: it’s modeled on Yehudah ha-Levi’s famous, stirring ציון הלא תשאלי but uses a characteristically Ashkenazi rhyme scheme, vocabulary, and theme. It ends on, of all things, with a hopeful lilt.

One of Maharam’s students, R. Shimshon ben Tzadok, meticulously recorded his master’s habits in the manner of the pietists; much of R. Shimshon’s halachic work Tashbetz Katan is based on Maharam’s personal practices. Here is a typical example from the opening of the book, on the laws of Shabbat:

ספר תשב"ץ קטן סימן א

מהר"ם ז"ל רגיל לעולם בליל שבת לאכול עם שקיעת החמה ואינו ממתין ממש עד הלילה. וגם אינו אוכל מיד כשבאים מבית הכנסת בעוד היום גדול…ואפילו כשהוא מתענה אוכל עם שקיעת החמה…אבל כשהוא מתענה תענית חלום בערב שבת מתענה עד צאת הכוכבים דכיון שהוא חמור כל כך עד שיתענה תענית חלום אפילו בשבת לכתחלה.

“The Maharam was accustomed to always eat at sunset on the night of Shabbat and not to wait until actual nightfall. But he would not eat immediately upon returning from the synagogue… Even when he is fasting he would eat at sunset. However, if he were fasting a taanit chalom (a fast in response to negative portents in a dream) on Friday afternoon, he would continue to fast until tzeit ha-kochavim (the time when three stars are visible in the night sky), because it is a serious matter such that he would fast a taanit chalom even lechatchila (ab initio) into Shabbat.”

This small window into Maharam’s world shows him to be suffused with halachic rigor and mystical insight; self-assured but subsumed by piety. For a moment, we can imagine the angle of the light through his window as he sits down to his first meal of the holy Shabbat.

An Unusual Imprisonment

Maharam’s well-documented imprisonment is the subject of legend and lively scholarly debate. Maybe we’ll get into the (absolutely fascinating) weeds of the evidence and its interpretation in a dedicated newsletter someday, but here are the basics: German Jews in the later thirteenth century were caught in an unenviable power struggle between local and regional rules. During the long interregenum period of 1254–1273, during which authority over German lands was in dispute, local nobility asserted the right to tax Jews. Taxing Jews was a lucrative business, so, in the period after Rudolph I was crowned emperor, he tried to wrest back control over taxation rights from the nobles. He did this by asserting an old theoretical concept that Jews are servi camerae regis, serfs of the royal treasury. (This was all the rage among the European kings consolidating their power in the thirteenth century.) In theory and practice, this wasn’t all bad, in the sense that the king was also bound to protect his serfs. However, it was really bad when Jews were being double-taxed as proxies in a turf war that also happened to make an excellent source of cash.

Maharam reputedly refused to be ransomed due to the impossible precedent set by the exorbitantly high price he was sure to extract from the local Jewish community. His failure to be redeemed, whether or not at his own behest, seems to have been tied up in the political consequences of capitulating to Rudolph’s claim over Jewish taxation. In other words, the problem was not one of simple ransom but of the political status of Jews. In a medieval Western Europe in which Jews were always conditionally granted rights of settlement, this was a very big deal.

And so, Maharam remained in prison until his death. He was, however, given a sentence of quasi-house arrest, with some, though not unlimited, access to his students and to books.

Enduring Influence

As if all that weren’t enough, Maharam was both the student and the teacher of the most prominent of minds in Ashkenaz. When he set up his own yeshiva in Rothenburg, Maharam became the fountainhead of important vectors of Jewish legal tradition.

Through his preeminent student R. Asher ben Yechiel (Rosh), who moved from Germany to Toledo, Spain with his young son Yaakov, the future author of the Arbaah Turim, Maharam was to become a formative influence on the Tur. The Tur, of course, forms the backbone of the Shulchan Aruch, from which halacha flows into modernity and down to us. The Rosh also transplanted Maharam’s Tosafot onto Sefardi soil, instituting their study in his new milieu.

Maharam’s Torah also seeded Ashkenaz with books of halacha, including the Mordechai, Haggahot Maimoniyot, Shaarei Dura, the Agudah, and the Tashbeẓ (Katan). These, in particular the Mordechai, were the sources of the Rema’s glosses on Shulchan Aruch, bringing in the Ashkenazi legal tradition and rendering the Shulchan Aruch the definitive code for Klal Yisrael.

Maharam Reads

You can read Maharam’s famous kinah here, with accompanying translation in English and Gershom Scholem’s searching German.

For an overview of the state of the evidence on Maharam’s imprisonment (along with the author’s take), see the late R. Eitam Henkin’s “728 Years After His Death, We Reassess the Ransom of Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg” in Tablet Magazine. This addresses some of the questions raised in Dr. Simcha Emanuel’s recent book עטרת זקנים.

Joseph Isaac Lifshitz’s Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg and the Foundation of Jewish Political Thought (Cambridge University Press, 2015) explores the political dimensions of Maharam’s rulings; it’s an expensive academic book (there are currently some reasonably-priced used copies on Amazon), but you can get a condensed version of the book in this freely-available article. (For the classic take, see I. A. Agus’s take here; you can read it for free online if you create a login.)

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

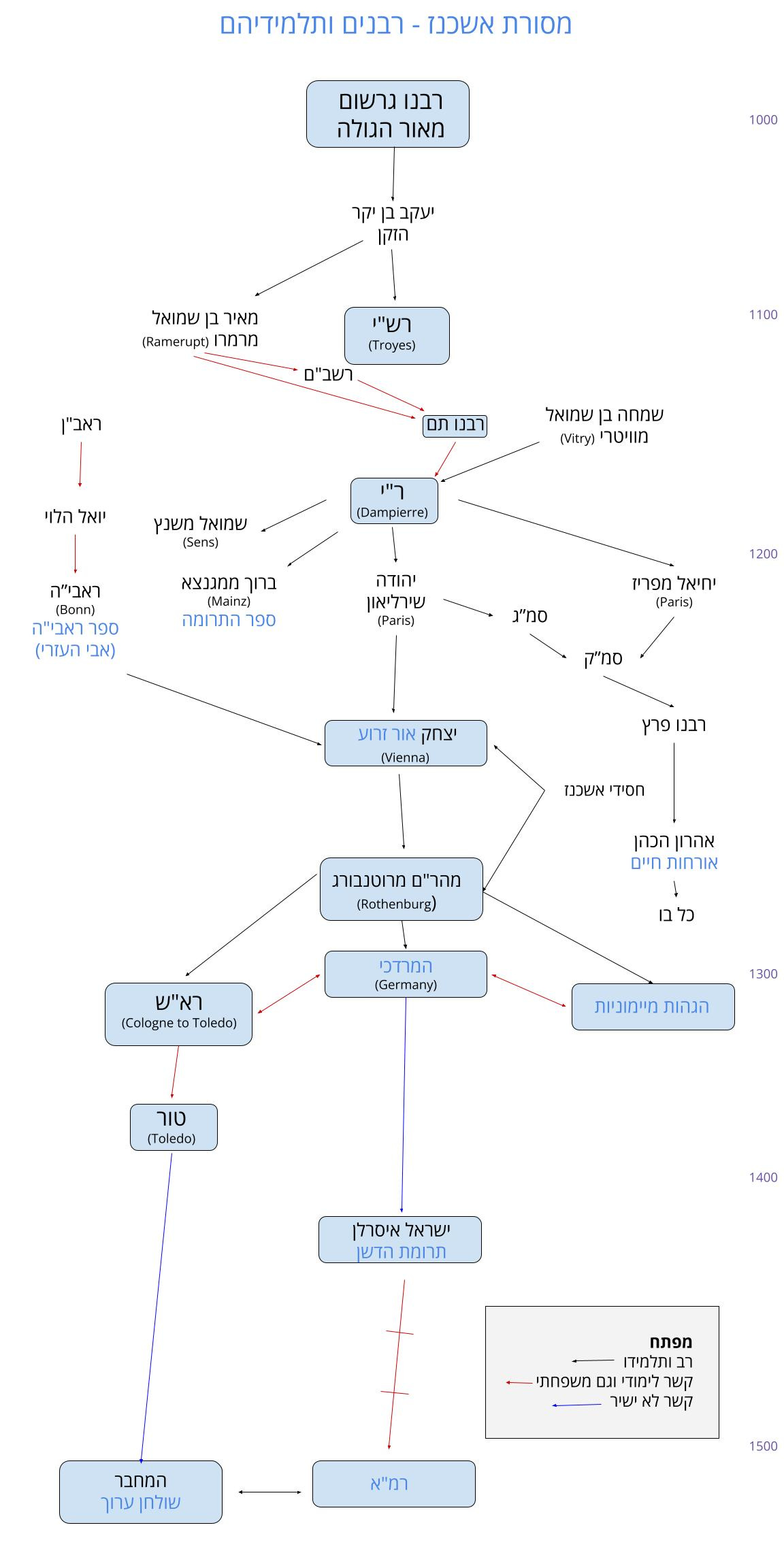

I made this (slightly intense) chart of Ashkenazi halachic transmission for you! (It’s not as intense some you’ll find out there, I promise.) It illustrates teacher-student relationships rather than family lineage, though family relationships are marked in red. You can trace the tradition from Rabbenu Gershom Maor ha-Golah, whose students taught Rashi, all the way down to the Shulchan Aruch with Rema’s glosses. You’ll notice that towards the end, there are bigger, more indirect leaps as more halachic works get written and into circulation. As well, it summarizes the relationships we’ve traversed over the last several weeks. I hope you’ll find it helpful. I made it in Hebrew, but I’m happy to take requests for an English version, if you’d like. (You can hit reply or comment below.) Click for a bigger image in Google Draw, where you can make yourself a copy or save a shortcut.

Maharam Twitter Thread

ICYMI or want to bookmark…

Next Coffee Date

Next week we’re off to sunny northern Africa to meet up with Rabbenu Chananel, who wrote the first Talmud commentary of the Judeo-Arabic world and set in motion a deluge of learning.

The first of the Hapsburgs, who literally ruled, in various iterations, until World War I. Rudolph I’s coronation had been preceded by a protracted period of political turmoil.

Thanks for the very cool chart on influences. I know that during the same time period, Provence had a very active Jewish community that often acted as a bridge between Sephardi thought and the non-Arabic speaking Ashkenaz world (e.g., the ibn Tibbon family's famous translations). Is there much back and forth between the Northern French/German Ashkenaz world that you've been detailing and the Provencal/Southern French world that straddles between Ashkenaz and Sepharad?