Coffee with the Rif

☕ Rabbi Yitzchak Alfasi learned from the greats of Kairouan, built a life in Fez, and the, in an unlikely last act, transplanted his Torah to Spain, where it took root and flowered...for centuries.

Hi, it’s another Tuesday in 5783, but some people seem to think the calendar’s changed? Yeah yeah, I’m an insufferable stickler, in case you didn’t already know. In my defense, January 1, Julian and certainly Gregorian, is of recent vintage; no one in the Middle Ages, and especially not the Rif, had any idea what it meant. (Even the Romans only sort-of used it.)

Today: We’re on the ground as the Rif births one of Judaism’s most influential works of all time. Is there political intrigue, intellectual grit, a surprising last act, and plenty of Torah? Of course there is! Ready for it?

Back in Qalat Hammad

For a hot minute, the city of Qalat Hammad was the glittering capital of Ifriqiya, in what is today Algeria (it’s now a UNESCO World Heritage Site).1 It was founded in 1007 by a branch of the Zirids, the Berber Muslim dynasty that ruled from Kairouan (Qayrawan),2 where we hung out last week with Rabbenu Chananel. When the neighboring metropolis was attacked and destroyed in 1057, Kairouan’s loss was Qala’s gain. It was all over by 1152, when the extremist Almohads (al-Muwahiddun, “the Unifiers”), another Berber dynasty from the Maghrib, destroyed the city. (Yep, these were the same Almohads that caused so much strife for Ibn Ezra and his fellow Jews in Spain.)

The Rif, R. Yitzchak Alfasi (1013–1103), gives few details of his life. Much of what we know comes from R. Avraham Ibn Daud’s twelfth-century account in Sefer ha-Kabbalah, which was also an important source for us last week. According to Ibn Daud, Rif was born in Qalat Hammad, and we do see other Rishonim refer to him as ha-Kala’i, “from Qala.” He was apparently educated at Kairouan; Ibn Daud states that the Rif’s teachers were Rabbenu Chananel and Rav Nissim Gaon (Rabbenu Chananel’s disciple and colleague). What is certain is that Rabbenu Chananel’s Talmud commentary was a formative influence upon the Rif, who based his magnum opus squarely upon it.

The Rif settled in Fez, Morocco, where he lived for most of his long life and from which he gets his surname (al-Fasi, “of Fez”). His impetus to leave was entirely external: in 1088, when he was an elderly man of seventy-five, Rif was impelled to flee Fez when he was denounced to local Muslim authorities. He settled in Lucena, Spain, the city of Torah scholars and poets. A year later, when the great R. Yitzchak Ibn Ghiyyat, who was head of the Lucena yeshiva, passed away, the Rif filled the position. Among his important students in this unlikely last act were the Ri Migash, possibly R. Yehuda ha-Levi, and R. Baruch Albalia. Ri Migash was to become the teacher of one Maimon ha-Dayan, the father of Rambam.

The Little Talmud

Rif’s crowning achievement, the one that changed Jewish history, was his Sefer ha-Halachot, also known as Halachot Rabbati (“the large halachot”) or the Talmud Katan, “the little Talmud” (or, “the abridged Talmud”). As the name implies, Rif excerpted those parts of the Talmud that were relevant in his day, following the Geonic curriculum. This meant that he covered the orders of Moed (holidays), Nashim (family law), and Nezikin (torts and other areas of civil law), as well as the tractates Berachot (on prayer) and Chullin (on kosher slaughter). The practical material in the orders Kodashim and Toharot, such as laws of mezuza, tefillin, and the writing of Torah scrolls, he excerpted under the section known as Halachot Ketanot (“small halachot”). At the same time, he omitted those parts of the tractates mentioned of no practical application, such as the parts of Pesachim that deal with Korban Pesach (like, the actual paschal sacrifice) and the parts of Yoma that deal with the Kohen Gadol’s service in the Beit ha-Mikdash (Jerusalem Temple). Rif also omitted most—though notably not all—of the aggadic (narrative as opposed to legal) portions of the Talmud. He left in those aggadot that he believed to be morally edifying and relevant.

What this achieved, in line with Rif’s stated purpose for the work, was to allow more people to study the Talmud, especially at a time when copying and acquiring the entirety of the massive work was impossible for most. Generations of students learned Gemara from the “the Little Talmud,” including times when the Talmud was banned, as occurred in early modern Italy—the ban explicitly permitting the Rif’s Halachot. Moreover, the Halachot inspired a huge commentarial and critical literature and served as the backbone or core resource for numerous works, including Sefer ha-Itim, the Rosh, the Ran, Sefer ha-Chinuch, and the Mordechai, among many others.

A Commentary? A Code? A Summary? Yes.

However, serving as an accessible summary was only one function of the Rif’s Halachot. Rif also offered his own terse explanatory notes modeled on Rabbenu Chananel’s; importantly, he brings other relevant sugyot to bear on the local sugya. In this, he assembled for the reader the needed background information to understand what is happening in the text before them.

Rif was also interested in reconciling each sugya down to its final conclusion, meaning that he issued important rulings in the commentary. He sometimes discusses his rulings in conjunction with those of the Geonim, citing the great gaonic compendia of law: the Sheiltot, the Halakhot Pesukot, the Halakhot Gedolot, as well as the works of his senior contemporary, the “last gaon” Rav Hai ben Sherira. In its function of deciding halacha, Rif’s summative commentary also acts as a code.

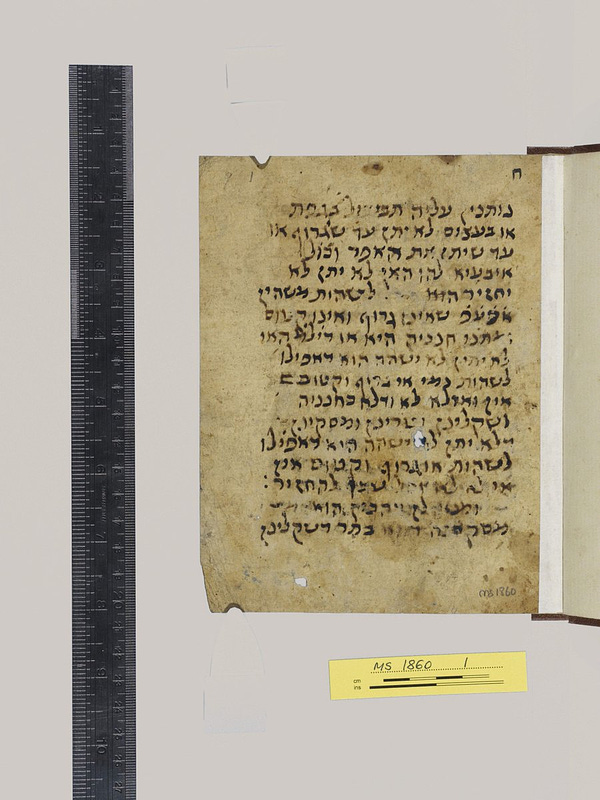

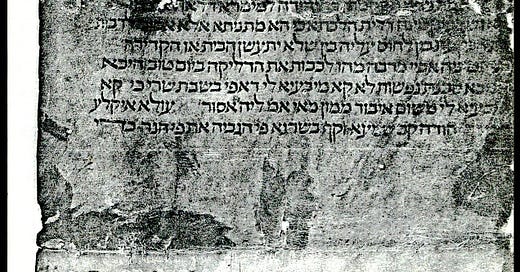

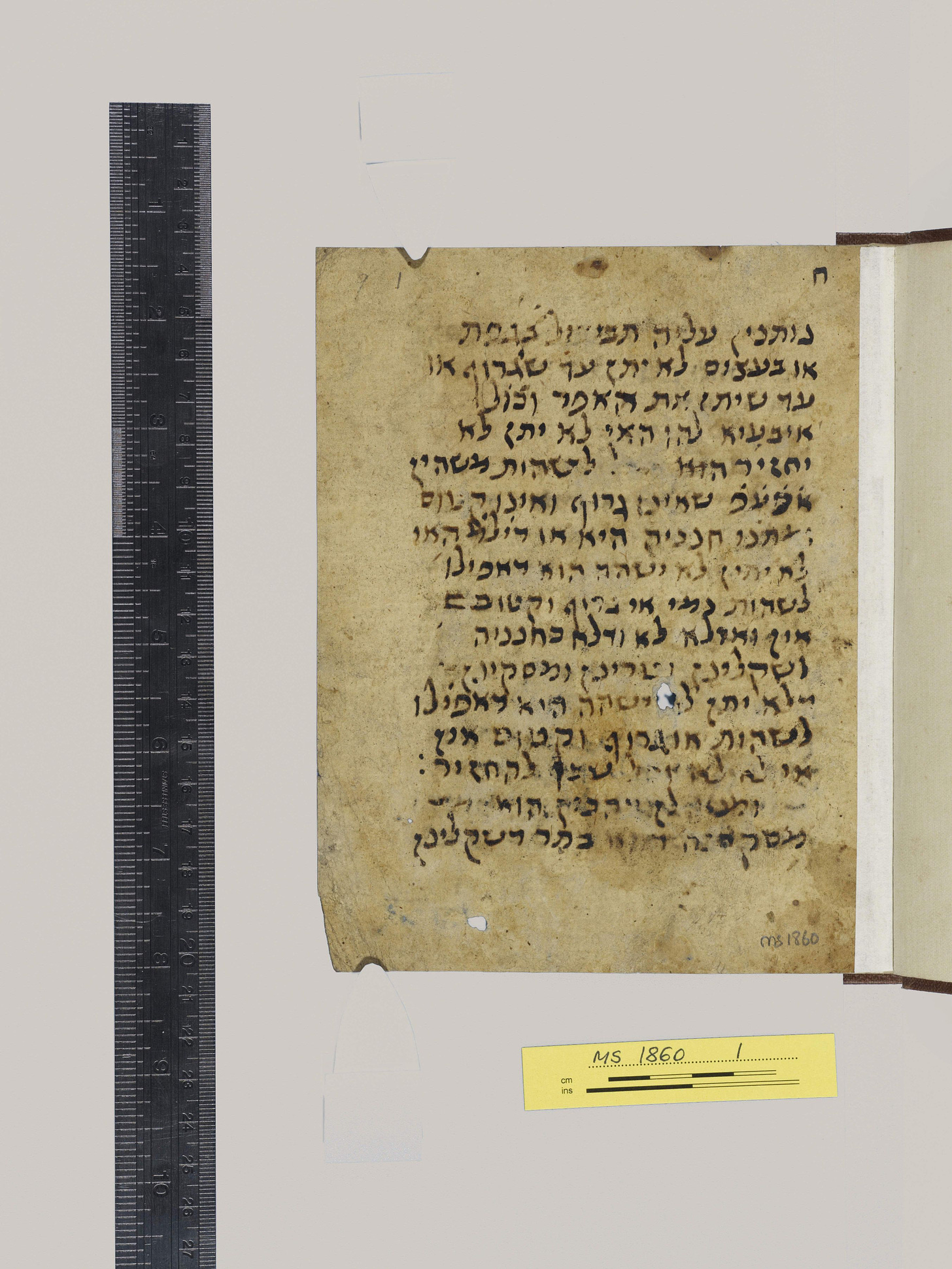

The publication history of the Rif is unusually gnarled; the first two printed editions, Constantinople 1509 and Venice 1521, are based on different groups of sources and are quite distinct from one another. The Rif printed in the Vilna edition of the Talmud, which forms the basis of most present editions, is itself based on the eclectic second (Venice) printing. Unlike his contemporaries in Ashkenaz, Rif wished for his revisions to be adopted and to supersede his earlier remarks. For instance, the Baal ha-Maor (R. Zerachia ha-Levi) notes, in a discussion of the validity of a stepson (or possibly brother-in-law) serving as a valid witness:

מפני זה חזר בו הרי"ף ז"ל וצוה למחוק כל זה שכתב מן ועוד דכד מעיינת בדברי גאון ז"ל וכו' עד סיפא וצוה לכתוב במקומו ועוד האי דדייק ואמר אף כמו כן

For this reason, Rif, of blessed memory, went back and instructed that that which he wrote should be erased, from “and also as we have seen in the words of the gaon of blessed memory” and so on, until the end, and instructed that in its place should be written, “and also Hai made a correction, stating that it was indeed this way.”3

Critical editions, including newer manuscript evidence, are happily coming out now.

When Rif passed away, Moshe Ibn Ezra, the consummate Andalusi Hebrew poet, wrote in euology, “Inside this grave the very light of wisdom is buried, and the world is left blind… within him are hidden away the luchot [the Tablets of the Ten Commandments] and the aron [Holy Ark].” Yehuda ha-Levi4 lamented:

הרים ביום סיני לך רעשו כי מלאכי הקל בך פגשו ויכתבו תורה בלוחות לבך.

Mountains trembled before you as at Sinai / as the angels of G-d came to meet you / to write the Torah on the tablets of your heart.

Rif Reads (and a Listen)

Dr. Ezra Chwat, author of a new critical edition of the Rif, on the Seforim Chatter podcast discussing the life and work of the Rif.

Dr. Chwat also wrote a series of four blog posts, mostly in Hebrew, analyzing halachot found in manuscript versions of Rif (and not in our “standard” printed version). They can be downloaded as a PDF or read them here, here, here, and here.

Also a technical read, but in English, Dr. Ron Kleinman explores a legal innovation of the Rif’s and traces its influence in “The Power of Monetary Customs to Override the Law: On the Innovative Approach of Rabbi Isaac Alfasi and His Influence on Medieval Spanish Rabbis.”

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

WebShas is a project of the early-aughts internet, which is to say, it’s awesome and has withstood the test of time. Created and maintained by R. Mordechai Torczyner, WebShas is a simple interface the offers powerful functionality: creating a topical index of the Talmud. For example, I was just looking up where in the Gemara kosher species of fish are discussed; it’s here.

Rif on Twitter

ICYMI.

Next Coffee Date

Okay, get ready…next time we’re (gulp) hanging out with RAMBAM. If, you know, he has the time for us...

More images are available here, on Archnet.

Berbers constitute a large, important north African ethnic group that was Islamized during the Arab conquests of the seventh century. Even today, vernacular Moroccan Arabic is significantly different from other spoken forms of the language due to an admixture of Berber vocabulary; and Berber remains an official, and living, language alongside Arabic in contemporary Morocco.

You can see in the our received text indeed has the Baal ha-Maor’s correction.

Well, possibly: this poem is often attributed to Yehuda ha-Levi, though it’s poorly attested.

Fascinating. Would the Rif have been copied and transmitted as a single codex, or would it have been assembled with other, perhaps related, texts?