Coffee with Rabbenu Chananel

☕Rabbenu Chananel, author of the first Sefardi Talmud commentary that has come down to us, managed to bridge the worlds of the Geonim in Bavel and Eretz Yisrael through his dual heritage.

Hi! Welcome to medieval north Africa. After several weeks in the snowy climes of France, Germany, and Bohemia, we’re off to the sunny Maghrib (literally, “the West” in Arabic). We’re going to see how Talmud learning goes down far afield from the old center of the Jewish culture in the Islamicate world, Baghdad. As usual, we’ve got intrigue, swashbuckling, the guts from which we construct history, and groundbreaking Torah. All the good stuff.

The Reish Bei Rabban Will See You Now

Rabbenu Chananel ben Chushiel (d. 1055/6) was the towering figure of Kairouan (al-Qayrawan), in present-day Tunisia, having inherited the helm of the city’s yeshiva from his illustrious father, R. Chushiel ben Elchanan. The yeshiva of Kairouan was, by Rabbenu Chananel’s time, neither fledgling nor minor, sort of a Stanford to the Harvard and Yale of Sura and Pumbedita. Neither in prestige nor in religious power did the Kairouan yeshiva rival the great academies of Bavel. It did, however, partly by virtue of geography and demography, partly by virtue of scholars like Rabbenu Chananel, attain a degree of halachic éclat and independence heretofore unknown.

From Bari Comes Forth Torah

Rabbenu Chananel’s father, R. Chushiel, is known within Jewish tradition from the story of the four captives in R. Avraham Ibn Daud’s twelfth-century Sefer ha-Kabbalah, an important (because rare) chronicle of rabbinic history. This story establishes the origins and importance of Jewish communities West of the old centers of Bavel (roughly today’s Iraq and Iran) and Eretz Yisrael. According to the story, four prominent rabbis travel via sea to a convention, departing from Bari, a city in Byzantine southern Italy. Bari and neighboring cities, up north to Rome, are indeed well-attested as early centers of Torah learning in medieval Europe. We see our old friend Rabbenu Tam relating, in Sefer ha-Yashar, “They would say of the citizens of Bari, ‘from Bari comes forth Torah and the word of G-d from Otranto’”(בני בארי שהיו קורין עליהם כי מבארי תצא תורה ודבר ה' מאוטרנטו).1

According to Ibn Daud, sometimes known as “Raavad I,” these four rabbis, R. Chushiel being one of them, were captured by pirates. So okay, no parrots (they’re native to South America, Australia, and New Zealand) or rum (you had to be Marco Polo to encounter some), but pirates were a very real, very dangerous presence in the medieval Mediterranean. Fanciful as it sounds, this is a highly plausible scenario. Recognized as prominent figures, the four rabbis were ransomed at high prices, another sadly realistic detail. They were redeemed by communities in Egypt, Ifriqiya (meaning the Islamic region west of Egypt), and Spain:

ומכר את ר' חושיאל באפריקיא בחוף הים ומשם עלה למדינת אלקירואן שהיתה בימים ג ההם חזקה מכל מדינות ישמעאל שבארץ המערב. ושם היה ר' חושיאל לראש ושם הוליד את רבינו חננאל בנו.

The commander…sold R. Chushiel on the coast of Ifriqiya. From there the latter proceeded to the city of Qayrawan, which at the time was the mightiest of all Muslim cities in the land of the Maghrib, where he became the head [of the academy] and where he begot his son Rabbenu Chananel.2

Ibn Daud, Sefer ha-Kabbalah

Among the earliest surfaced and published findings from the Cairo Geniza, however, are letters to and from R. Chushiel. One of these states plainly that R. Chushiel is awaiting his son’s arrival from “the land of our birth, to come settle in the land of the Yishmaelites,” i.e., Islamic lands.3 A twist is that the son’s name is given as the similar but not identical Elchanan, not Chananel.4 Also, the recipient of the letter is R. Shemariah ben Elchanan—another of the four captives. To add to the confusion, the letter mentions a R. Nissim, probably the grandfather of the Rabbenu Nissim Gaon who would become Rabbenu Chananel’s protégé and successor. This evidence has been marshalled to dispel the historicity of Ibn Daud’s account. It seems to clearly say that R. Chushiel’s son was born elsewhere, not in Kairouan, and to have arrived there of his own volition, not through captivity (although in Ibn Daud, it was the father who was ransomed, not the son).

I think this is a genre error. It is actually amazing how much the geniza evidence supports Ibn Daud’s account. Here we have a R. Shemariah and a R. Chuhiel ben Elchanan that are contemporary colleagues; we have a solid source (though, like most premodern evidence, inconclusive) for the immigration of R. Chushiel’s family from Christian territory to Islamic territory; and general corroboration of the familiar relationship and stature of R. Chushiel and Rabbenu Chananel. Yeah, there are no for-sure pirates in the letters, but the evidence therein is consonant with so much that we know. The fact that Ibn Daud’s story reflects reality in many of its details seems much more important to me than the absence of outside evidence of the captivity element.

Greetings from Kairouan

By the time R. Chushiel and son rolled up to Kairouan, it had become something of an African entrepôt and a significant Jewish community. Jews are well attested there from the ninth century on, although they were likely present earlier (the city was founded in 670, after the Muslim conquests). For instance, trumped candidates for the Baghdad exilarchate, the political representative of the Jewish community to the Muslim government, were known to have wound up in Kairouan, including Mar Ukva. Kairouan was also the home city of the Neoplatonist and physician R. Yitzchak Israeli, who usually earns the moniker of “first Jewish philosopher.” We could, and probably will, quibble about what exactly we even mean by “Jewish philosopher” and on what grounds there could be a “first,” but what’s for sure is that Israeli was the progenitor of a philosophical, rationalist tradition foundational to future Sefardi culture.

And, we couldn’t let Kairouan go without mentioning the visit of the mysterious and fascinating Eldad ha-Dani, traveler and tale-barer who claimed (with some good evidence, by the way) to be a representative of the Ten Lost Tribes. (He maintained, as indicated by the name by which he is known, that he was from the Tribe of Dan.) Eldad had halachic traditions that diverged from that the the Bavli yeshivot, which occasioned a correspondence between the rabbis of Kairouan inquiring as to the authenticity and authority of Eldad’s halachot. (Will we be having some possibly-not-anachronistic Ethiopian coffee with Eldad ha-Dani someday? Of course.)

Ibn Daud goes on to give us a number of details about Rabbenu Chananel’s role in the cultural life of Kairouan:

אחר פטירת רב חושיאל נסמכו במדינת אלקירואן בנו ותלמידו רב חננאל ורב נסים בר' יעקב בן שאהון שקבלו מר' חושיאל. וקבל רבינו נסים הרבה מרבינו האיי שהיה אוהבו מאד ושולח לו ספרים בתשובות כל ספיקותיו על יד…ורב חננאל עשיר גדול היה שהיו בקירואן סוחרים הרבה מטילים מלאי לכיסו. והיו לו ט' בנות. ועשרת אלפים זהובים הניח אחר מותו.

After the demise of R. Chushiel, the rabbinate in the city of Kairouan passed into the hands of his son and disciple R. Chananel and R. Nissim b. Yaakov Ibn Sahin, both of whom received [the tradition] from him. R. Nissim also received much from Rabbenu Hai, who held great affection and sent him letters in response to all of his problems without exception… R. Chananel became a very wealthy man owing to the fact that many merchants in Kairouan showered him with capital. He had nine daughters [to whom] he left ten thousand gold pieces after his death.5

R. Avraham Ibn Daud, Sefer ha-Kabbalah

According to Ibn Daud’s account, Rabbenu Chananel and his student R. Nissim represent the apex of rabbinic achievement in Kairouan. After them, Torah learning shifted westward, to Fez, Seville, Córdoba, Lucena, and elsewhere in Spain, which indeed we see in the historical record.

Rabbenu Chananel’s Talmud Commentary

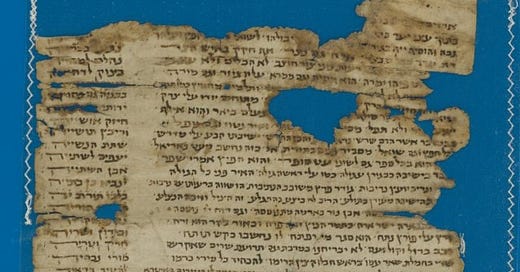

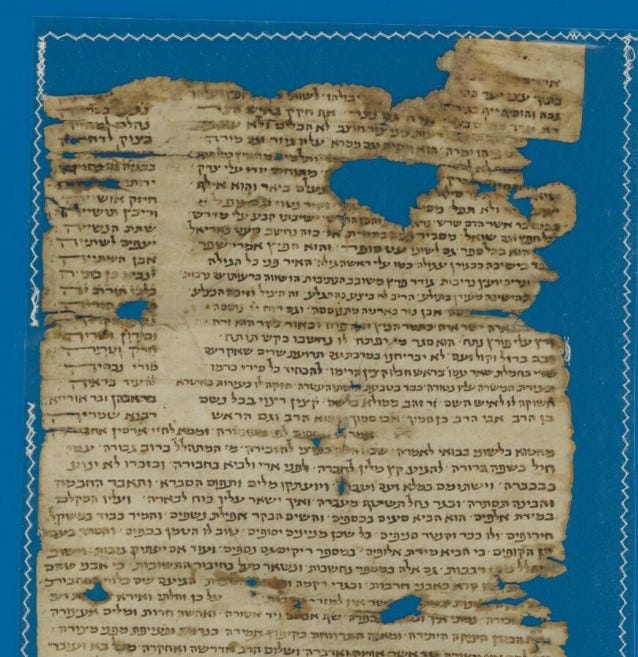

Like all groundbreaking works that seemingly come out of nowhere, Rabbenu Chananel’s Talmud commentary is built upon a foundation he inherited. The fragmentary Talmud commentary that has come down to us from Rav Hai Gaon is enough to show that Rabbenu Chananel often cited Hai Gaon verbatim. He is clearly indebted to the great legacy of Geonic learning.

And yet, what Rabbenu Chananel did for Talmud study revolutionized Jewish life. First, his commentary provided scaffolding for the student without the means to travel to Bavel, much in the way that Rashi’s commentary opened the Talmud before students without access to the Rhineland yeshivot. This, as the technocrati say, “disrupted” the authority of the ivied academies of the east, as we can see from the their increasingly frustrated letters requesting donations coming out of Baghdad in the tenth century.

Rabbenu Chananel’s full commentary has not come down to us; we know that he produced more than we have, though it’s unclear whether he commented on the entire Gemara. What is clear is that his commentary was comprehensive vis-a-vis the aspiring rabbi or dayan in the Maghrib in the eleventh century. Rabbenu Chananel provides a clear, helpful topical summary running alongside the Gemara. Rather than line-by-line glosses, he covers subject areas, giving you what you need to know to understand the local sugya. Rabbenu Chananel's explanations of difficult words, often making use of his knowledge of Arabic and Greek,6 wend their way into the Aruch of Natan ben Yechiel of Rome, the first Talmudic lexicon.

His commentary also created a paradigm that would prove enduring in Sefardi Talmud learning, both in its form and content. For one, it would provide the stylistic template followed by the Rif and the generations of scholars who accessed Talmud chiefly through Rif’s Talmud Katan, “Little Talmud.” In addition, Rabbenu Chananel’s commentary set a precedent of reconciling the sugya to its practical halachic implications, which would remain a focus of Sefardi parshanut ha-Gemara (Talmudic analysis) henceforth.

Interestingly, Rabbenu Chananel brought his father’s Italian traditions down in his commentary, even as his evident respect for the Geonim pervades it. He does not hesitate to assert his father’s masora (received tradition) where it differs from that of the Geonim. Similarly, Rabbenu Chananel reintroduced, via his Talmud commentary, the use of the Yerushalmi (the Talmud of Eretz Yisrael), which, following him, enters the mainstream of Sefardi learning. He also emphasized the importance of consulting the Tosefta and the halachic Midrash collections. In this way, way out west, he bridged the worlds of Bavel and Eretz Yisrael and nourished the very foundation of Sefardi Torah learning.

Rabbenu Chananel Reads

There are not a plethora of reads on Rabbenu Chananel, especially in English, unfortunately, but here are a few:

Rabbi Yehuda Turetsky has a shiur on Rabbenu Chananel’s Talmud commentary (YU Torah).

R. Shmuel ha-Nagid, the great statesman-poet of Granada, wrote a poetic eulogy—in Aramaic—for R. Chushiel, which he addressed to Rabbenu Chananel (“לְאֻמְּתֵהּ רַבַּנָא חֲנַנְאֵל רָחֲמִין מִן שְׁמוּאֵל זוּטָא דְכֻלֵּי חַכִּימִין שְׁלָם טָב וְנִחוּמִין”). You can read it here.

In Hebrew, see Prof. Israel Ta-Shma’s history: הספרות הפרשנית לתלמוד באירופה ובצפון אפריקה חלק ראשון: 1200-1000 (Magnes, 1999).

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

I’m happy to say that I’ve finally finished my Twitter thread index! You can easily browse alllll the threads I’ve done, alphabetically or by theme. Right now I have Ashkenaz, Sefarad & Mizrach, Talmud Commentary, Torah Commentary, Halacha, Jewish Thought, and Piyut & Poetry. I’ll add more themes as they come up.

Rabbenu Chananel on Twitter

Next Coffee Date

Next week, we’re finally catching up with the Rif, following him from Algeria to Fez to Lucena.

Yep, this is a rather pregnant paraphrase of Yeshayahu 2:3. In Sefer ha-Yashar, Teshuvot section, siman 46.

Sefer ha-Kabbalah, trans. Gerson D. Cohen (with slight modification in the spelling for consistency); Eng. p. 64, Heb. p. 47.

T-S 28.1, lines 58-61: כי יציאתנו מארץ מולדתנו לעבור להתגודד בארץ ישמעא’ . Early Rishonim sometimes refer to Rabbenu Chananel as being “of Rome.”

It may be that Rabbenu Chananel had a brother named Elchanan, or, more likely, that medieval people were a lot less standardized about names than we are and this is a variant by which Rabbenu Chananel was also or at one time know.

Cohen, ed., Eng. pp. 77-78, Heb. pp. 57-58.

Byzantine south Italy was a Greek-speaking region.