Coffee with Rabbenu Tam

☕ Don't be fooled by the chill name: behind the Tam is a fierce intellect unafraid to stake his place and add his voice to the great conversations of the Talmud (and his day).

Hello! Welcome back to the Middle Ages. We may not have Penicillin, but hey, Tosafot we’ve got. (Also forks, except for maybe northern Europe. Should you ever need to bask in killjoy historical pedantry, I once live-tweeted my family outing to Medieval Times. I made a bingo card and everything.)

Today we’re back in Ramerupt (a.k.a. The Middle of Nowhere, France, Except that Major Torah Scholars Lived There) to meet with another spirited Rashi grandson, Rabbenu Tam.

Rabbenu Tam—He’ll Call You

Rabbenu Tam was the younger brother of Rashbam (who we hung out with last week) by some fifteen or twenty years: he was born c. 1100, while Rashbam was born c. 1080 to 1085. His moniker is a reference to his given name, Yaakov; his Biblical namesake was known as איש תם יושב אהלים—“a mild (tam) man, dweller in tents.” This is actually hilarious because Rabbenu Tam was anything but tam. He was fierce, opinionated, and like his big brother, self-possessed, even larger than life.

Too young to have learned with his famous grandfather, Rashi, who passed away in 1105, Rabbenu Tam was educated by his father, R. Meir ben Shmuel (the scholar-in-his-own-right who had married Rashi’s daughter Yocheved), his brother Rashbam, and a student of Rashi’s, R. Yaakov ben Shimshon. But if he missed the Harvard education (Rashi being Harvard in this scenario), well, he pretty much went to Yale, Oxford, and the Sorbonne. The world was his oyster. [Insert kosher metaphor here.]

Think Local, Act Global

And indeed Rabbenu Tam was worldly and wealthy, rubbing shoulders with Christian nobility and scholastics (some of whom addressed to him queries about Biblical interpretation), on top of being a renowned halachic authority, a jaw-dropping expert in Talmud, and a high-caliber poet. We’re not talking a few casual piyyutim here and there, which was pretty much de rigueur in the wacky Middle Ages. We’re talking first Ashkenazi poet to introduce rhymed meter into piyyut, maintained poetic correspondence with Ibn Ezra level poet here. One of his poems is a paean to taamei ha-mikra (the cantillation marks in the Bible). Didn’t see that coming, did you?

Rabbenu Tam was hailed as the major decisor of the age, not only in Ashkenaz but from Spain to Italy. He finds a place as the very last named authority in R. Avraham Ibn Daud’s Sefarad-centric history of the transmission of the Oral Law: “We have heard that in France there are great scholars and geonim… There is one in the city of Ramerupt by the name of R. Yaakov.”1 Rabbenu Tam received queries from southern Italy, attracted students from as far away as incipient Russia, and garnered ire for trying to impose his decisions on Provence. Then there was that time Rabbenu Tam referred to his rabbinical court as the foremost beit din of the generation.2

In a stormy (and today, fragmentary) exchange with R. Meshulam ben Natan of Melun (another northern French city, nearer to Paris), Rabbenu Tam insisted on the primacy of his method and his customs. He threatened any who followed R. Meshulam’s customs with excommunication, excoriated him for his disrespect for Rashi and his house, and slammed his habit of emending Talmud texts, which Rabbenu Tam did not abide. This was just one of several such exchanges. Some of Rabbenu Tam’s own idiosyncratic, if brilliant, takes on halachic particulars remain known by his name to this day, in particular the order of the scrolls in tefillin and his determination of sunset.

One the Ground at the Birth of Tosafot

Rabbenu Tam is found, under the Prince-like notation ר”ת, throughout our Tosafot. That’s because it was in his beit midrash that Tosafot were born. There is healthy scholarly disagreement about what “Tosafot,” literally “additions,” refers to: are they additions to the Gemara itself? To Rashi? The prevalent view falls on the side of understanding them as additions to Rashi’s kuntres (“notebook,” the name by which Rashi’s commentary is known in the Tosafot), but in an important way Rabbenu Tam’s Tosafistic work is like tosafot to the Talmudic discussions. Though fiercely protective of the integrity of the text, Rabbenu Tam also felt at liberty to contribute, extending the argumentation, bringing in relevant sugyot from elsewhere in the Talmud, and coming to halachic rulings.

His method of study was continued by generations of students, spreading throughout France to Germany as well as Provence and ultimately involving dozens, if not hundreds, of Torah scholars. They refined, added, and edited the core of Rabbenu Tam’s readings of the Gemara.

That’s Not All, Folks

The Tosafot were not the only repositories of Rabbenu Tam’s halachic decisions. The responsa that we have today are collected in his Sefer ha-Yashar. Some of his halachot are preserved in Machzor Vitry. (Machzor Vitry is more than a prayerbook for the annual cycle of holidays; in the Ashkenazi tradition, it includes a wealth of halachic material relevant to the holidays and many other aspects of Jewish daily life. It is really a compendium or proto-code of medieval Ashkenazi halacha.)

Rabbenu Tam also wrote a Hebrew grammar, Sefer ha-Hachraot (ספר ההכרעות - “The Book of Decisions”), first published in the nineteenth century. In it, he steps into the very Sefardi debate between the classic grammarians Menachem ben Saruk and Dunash ben Labrat, defending Menachem against the criticisms levelled against him by Dunash. R. Yosef Kimchi, the father of the Tanach commentator Radak, would write his Sefer ha-Galuy in response to Rabbenu Tam, snapping back with a defense of Dunash. And so the hot takes continued some two centuries after the debate got started.

From the time of Rabbenu Tam, Ashkenaz and Sefarad edged ever closer as they discovered each other’s riches. Despite this, Rabbenu Tam’s method of working through a text remains a consummately Ashkenazi intellectual achievement.

Rabbenu Tam Reads

The classic scholarly treatments of Rabbenu Tam are in Hebrew in E.E. Urbach’s magesterial Baalei ha-Tosafot and in Avraham Grossman’s Chachmei Tzarfat ha-Rishonim. However, my pick for getting a sense of Rabbenu Tam’s world and achievements is the more general, absolutely excellent book by Dr. Ephraim Kanarfogel, The Intellectual History and Rabbinic Culture of Medieval Ashkenaz (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2012).

More recently, Dr. Rami Reiner, another outstanding scholar, wrote a book devoted specifically to Rabbenu Tam, רבנו תם: פרשנות, הלכה, פולמוס (Also on Kotar). You can read a review of it in English in Tradition Online. I haven’t read it yet, but it might just be the first thing I read with my brand new Kotar subscription. (Who am I kidding, I’m going to be reading twelve Kotar books at the same time.)

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

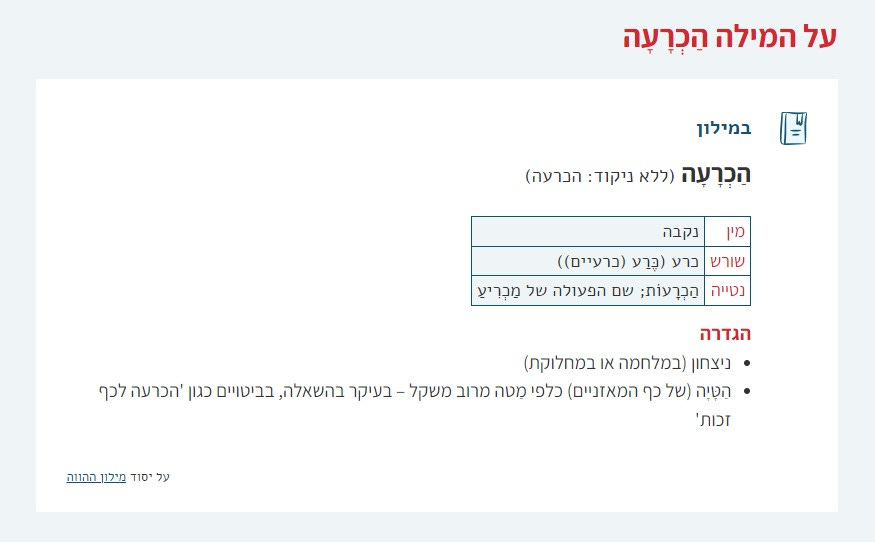

The Academy of the Hebrew Language has a great website. One of its features is full verb conjugation charts as well as general word definitions, historical usages, modern usages, and more. You can access all of these from the Google-like search bar at the top of every page. Above, you can see the entry for הכרעה, the term used in the title of Rabbenu Tam’s grammatical treatise.

It also has guides to standard Hebrew spelling and nikkud, such as this resource onניקוד אותיות השימוש.

Rabbenu Tam on Twitter

ICYMI!

Next Time

We’re still not done with the house of Rashi. Next week, we’re going to be in Dampierre getting to know Ri (Rabbi Yitzchak), the nephew of Rabbenu Tam and great-grandson of Rashi—and the architect of the Tosafot in the form we know them.

Trans. Gerson Cohen, Sefer ha-Qabbalah: The Book of Tradition by Abraham Ibn Daud, a Critical Edition (JPS, 1967), 88-89 (and see the note on line 480), Hebrew p. 66: “ושמענו שיש בארץ צרפת חכמים גדולים וגאונים…ואחר במדינת רומרו שמו ר’ יעקב."

Tosafot to Gittin 36b, ד”ה דאלימי לאפקועי ממונאץ.