Coffee with Rabbenu Bachya

☕ R. Bachya ben Asher made the burgeoning Kabbalistic movement more accessible in his beloved Torah commentary, where he also anthologized much midrash, some of it otherwise lost.

Happy medieval Tuesday, friends, and thanks again for your continuing support of my work! At this point we’ve made our way from the end of the period of the Geonim, around the year 1000, all the way to the 1300s. This journey of three hundred years has brought us to Iraq, Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, Spain, France, Bohemia, Germany, Italy, England, and, of course, Eretz Yisrael. (If you missed anything, you can always catch up in the archives.)

When I teach medieval Jewish history, I describe the thirteenth century as a time when “everything comes together and then falls apart.” We’ve seen elements of this massive transition in the last few newsletters: the changing Jewish demographics of the Mediterranean world which shift away from the Judeo-Arabic sphere towards Christian Europe (including in Spain, which is largely Christianized by 1300); the way that Christian attitudes towards Jews transform, resulting in increased efforts to convert Jews; and the movement of people and ideas that bring the traditions of Sefarad and Ashkenaz into closer conversation. This is the “come together” part. Towards the end of the thirteenth century, we begin to see European proto-states consolidate royal power and then use it to orchestrate large-scale expulsions of Jews from their realms. Conversionary efforts crescendo a century later, resulting in the riots of 1391-92 in Spain and the creation of thousands of Conversos. This is the “falls apart” part.

Rabbenu Bachya comes in right on the cusp of the “falls apart” stuff, managing to avoid much of the coming turmoil. He picks up the great intellectual currents brewing in late thirteenth-century Spain and passes them forward to us.

In this issue:

Rabbenu Bachya Will Tell You His Secrets

Active in Zaragoza (Saragossa), a major city of Aragon (northeast Spain), Rabbenu Bachya ben Asher Ibn Chlava1 (c. 1255-c. 1340) worked as a dayan (religious court judge) and darshan (preacher). Kabbalistic secrets, bubbling up among the Chasidei Ashkenaz of Germany and the mystical circles of Provence, had made their way across the Pyrenees a couple generations before Rabbenu Bachya. His teacher, the Rashba, was an initiate of its secrets, as was the Rashba’s own teacher and source of inspiration to Rabbenu Bachya, the great Ramban. But Rabbenu Bachya did something that even Ramban, who hinted at some of these secrets in his Torah commentary, did not yet do: Rabbenu Bachya wrote them down. Clearly, if discreetly, in a way that others could approach.

It’s notable and curious that Rabbenu Bachya never cites Kabbalistic traditions in the name of his teacher. It has been suggested that Rabbenu Bachya did not receive the traditions he knew from Rashba, or possibly that he had not secured his teacher's permission to transmit in his name. Rabbenu Bachya's Kabbalah is, rather, of the Gironese school, and when he cites a Kabbalist by name, it is generally Ramban.2

However, interestingly, research has shown that extracts or ideas cited by Rabbenu Bachya come from a range of other figures identified through other surviving texts. For example, other students of Rashba’s Kabbalah cite teachings in Rashba's name that appear in Rabbenu Bachya but without attribution. Among the other Kabbalists that Bachya drew upon is Asher ben David, the grandson of Raavad, and R. Yosef Gikatilla, an important Spanish philosophical Kabbalist. In his comment on Bereshit 32:10, Rabbenu Bachya names “Rabbi Yitzchak the son of the Rav, of blessed memory” (רבי יצחק בן הרב ז"ל) as “the father Kabbalah” (אבי הקבלה); it has been suggested that this refers to R. Yitzchak Sagi Nahor (“Isaac the Blind”), son of Raavad. Rabbenu Bachya also cites, in several places, the Zohar, which began circulating in Castile in the 1280s. His is an early attestation of Zoharic Kabbalah’s spread in Spain. He refers to it as “Midrash Rabbi Shimon ben Yochai.” This is all to say, Rabbenu Bachya brings together a rich assortment of Kabbalistic thought transpiring in his day.

A Beloved Torah Commentary

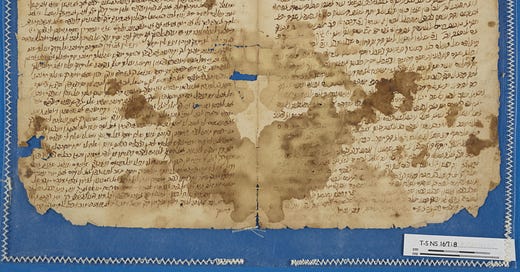

Rabbenu Bachya’s Torah commentary, which enjoyed wide circulation in the Middle Ages, as attested by the many manuscript fragments that remain, is distinguished by its clear writing style, interest in midrash, and ethical and Kabbalistic interests. It is deliberately anthological, compiling and summarizing earlier approaches to the Torah text. In so doing, Rabbenu Bachya preserves some midrashim that are otherwise unknown and did not come down to the present day, making it precious and eye-opening as to the nature of transmission of rabbinic midrash.

Rabbenu Bachya celebrates the multivalent aspect of the Torah, its ability to hold multiple coexistent levels of meaning at the same time. He explains in the Introduction to his Torah commentary (in rhymed prose):

ומפני שידעתי כי מפרשי התורה בספריהם הולכים על ארבעה חלקים ודרכים. יש מהם דרך הפשט רודפים. ויש מהם לדרך המדרש נכספים. ויש בוחר דרך השכל וחכמי המחקר המתפלספים, ויש בני עליה במסלה העולה בית אל עיני לבם צופים. רוו נפשם מדשן ויאכלו נופת צופים. נכנסו ברואה ולפנים מן הצופים. והשיגו השרש והענפים. על כן ראיתי לחלק באור ספרי זה על דרכים אלה כלם. למען יהיה לכל החלקים נשלם. בארבעה מעלות סלם .לעלות מן הנגלה אל הנעלם

Thus I understood that the commentators on the Torah, in their books, go by four divisions and ways. [1] There are those who chase after the way of peshat [the contextual reading]. [2] And there are others who are influenced by the way of midrash [classic rabbinic exposition]. [3] There is also he who chooses the way of the intellect and of the sages of philosophical inquiry, and [4] those who take the ‘highway that runs from Beit E-l,’3 the eyes of their heart envisioning,4 their souls full with richness, eating the drippings of the honeycomb.5 They entered in visions ‘from Mount Scopus and within,’6 attaining both roots and branches. For this reason, I saw fit to divide the explanation in this, my book, by all these ways, such that it will be complete in all aspects: in all four levels of the ladder, rising from the revealed to the concealed.

Rabbenu Bachya, Hakdama, Perush la-Torah

This quadripartite method is a variant of pardes interpretation, the acronym meaning peshat, remez, derash, and sod. Operationalized by Ramban, it reads the Torah simultaneously on the contextual level (peshat, the “plain” meaning of the words), according to rabbinic exegetical techniques (derash), on the symbolic or allegorical level (remez, “hint”), and finally on the esoteric level (sod, “secret”). Two interesting aspects of Rabbenu Bachya’s take on it just out at me here. First, he identifies the symbolic-allegorical read with rationalist philosophy. Second, he uses many terms to describe the Kabbalistic level of interpretation, selecting choice morsels of Mikra (Scripture) to allude to the depth of this method. He gives us an entire vocabulary of mystical experience here.

Two Unique Books

Rabbenu Bachya is also the author of two unusual books, as well as a commentary on Pirkei Avot. The better-known of these is Kad ha-Kemach (“Jug of Flour”),7 which incorporates his sermons. Unlike most works of homiletics composed in the medieval period, Kad ha-Kemach is arranged topically, treating topics of theological and ethical import. The topics are then arranged in alphabetical order, so that the first few topics are emuna (faith), ahava (love), orchim (guests, i.e. hospitality), and evel (mourning)—all beginning with the letter alef. Their form, however, is that of derashot (sermons). Several topics include expositions of parts of Tanach not covered in Rabbenu Bachya’s Torah commentary. For instance, under hashgacha (providence), he includes an extended analysis of Sefer Iyov (Job), which has at times been circulated independently (or along with other extracts from his works) as a commentary on Iyov.

The other book is called Shulchan Shel Arba (“Table of Four”), which is a treatment (in four parts, natch) of the rules and significance of festive meals. The fourth section deals with the future meal of the righteous in the enormous sukkah of the Livyatan (Leviathan), a messianic and mystical topic that brings together Rabbenu Yonah’s special interests and thought.

Rabbenu Bachya Reads

The three works of Rabbenu Bachya (Kad ha-Kemach, Shulchan shel Arba, and the Commentary on Pirkei Avot) have been published by Mossad ha-Rav Kook, edited by R. Chaim Chavel. They are also available, along with the original and English translation of his Torah Commentary, on Sefaria.

Rabbi Yaakov Taubes wrote an article on “Rabbeinu Bahya and the Case of the Mysterious Medieval Lightning Rod” (Lehrhaus).

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

Oxford Bibliographies are a great starting place for your research—their coverage of Jewish Studies is excellent. They offer solid and relatively up-to-date orientation as to what has been done on a given topic in the academic world. Some of the particulars might not be of interest to all (like critical editions), but the overview and sense of the subject area will be of wide interest. Here’s an example: the bibliography on the Jews of Yemen. (Yes, we’ll get to Yemen too, don’t worry!)

Rabbenu Bachya on Twitter

Next Coffee Date

☕ Next week we’re spending time with Ritva (R. Yom Tov Ishvili), another talmid muvhak (leading student) of Rashba’s.

Not to be confused with the other Rabbenu Bachya (Ibn Pakuda), an earlier Sefardi ethical writer and author of Chovot ha-Levavot (“Duties of the Heart”).

Recent research has sought to clarify Ramban’s relationship to other renowned Kabbalists in Girona, with some scholars arguing that Ramban’s tradition stands apart from the Gironese circles. He has thus far been accounted a member of these circles; I am including him broadly in the phenomenon of Gironese Kabbalah.

A referenceto Shoftim 21:19, which describes a “feast of Hashem” that takes place at Shiloh, along this road.

A reference to Yirmiyahu 31:14, a prophecy in which G-d declares, “I will give the priests their fill of fatness.”

A reference to Tehillim 19:11, “sweeter than honey, than drippings of the comb.”

See Brachot 61b; i.e., a place from which Beit ha-Mikdash is visible.

After Melachim Alef 17:14, in the story of Eliyahu and the widow; it is a miraculously sustaining jug of flour.

Thank you for this series; I’ve learned a lot. It helps that all these rabbis are now people, not just names.

About the “Pardes”: does anyone else actually define “remez”? I see it defined in modern works the way you do, but as far as I can tell Moshe de Leon just mentions the name without saying what it means, and Ramban never uses the term as a whole way of understanding Torah (the way he does pshat, drash and sod). The classical commentators seem to just use those three.

It’s nice to see Bachya defining the third way, but it doesn’t seem to go with the word “remez”.