Coffee with Ri of Dampierre

☕ Today we sit down with the chief architect of the Tosafot, Rabbi Yitzchak ha-Zaken, reverse-engineering the beloved (if often challenging) companion of every sugya of the Talmud.

Last week, we spent time with Rabbenu Tam, who kicked off the whole Tosafist enterprise of dialectical commentary on the Talmud. Dialectic is a jargony but nonetheless cool word that describes discourse that analyzes points of tension and then resolves conflicting viewpoints, which is exactly what Tosafot do. That’s where we get those classic, key Tosafot phrases like “You could say…but rather, one should say…,” or “If you want to argue that…,” and “There is no ground to claim…” Tosafot seek to harmonize information from other places in the wide Sea of Talmud that speak to the issue at hand, to come to a halachic decision, and to select the best answer to the operative question. What Ri does is articulate the questions and formulate this complex discourse. His Tosafot come down to us with many further additions and edits, but are in an important way the basis for “our Tosafot,” the ones that appear in the standard Vilna Shas.

In this issue:

Gentle Giant

Rabbi Yitzchak ben Shmuel, better known by his acronym as Ri ha-Zaken, “the elder Ri,” was a scion of the Rashi family twice over. A nephew and younger contemporary of Rabbenu Tam (both lived for the better part of the twelfth century),1 Ri was also the grandson of Simcha ben Shmuel of Vitry (we’ll get to why this is significant in a second) and the husband of Rashi’s great-great-granddaughter. That is, at a remove of four generations from Rashi’s beit midrash, Rashi’s Torah was a living, coursing force in France and beyond. And Ri was at the epicenter of this rich family legacy.

Okay, get ready to do some Yevamot-style family math here. (Yevamot is the tractate of the Talmud dealing with levirate marriage and infamously involves unwieldy family relationships.) Ri’s father Shmuel was the son of the aforementioned Rabbi Simcha, compiler of Machzor Vitry. Machzor Vitry, named after the town where R. Simcha lived,2 is important because it’s one of the earliest compendia of Ashkenazi halacha. Unlike their contemporaries in Sefarad, Ashkenazi Rishonim did not tend to write codes, instead preserving halachic rulings in responsa and commentaries like the Tosafot. This makes Machzor Vitry is a significant, early testament to Ashkenazi traditions, the ones that would, after winding their way through the hands of many, end up informing the rulings of the Rema in his glosses to Shulchan Aruch, the ultimate, sixteenth-century code of law that informs the minutiae of Jewish life down to our times.

R. Simcha, Ri’s grandfather, was also a leading student of Rashi’s. As we’ve seen, Rashi’s students tended to get shidduchim (marriage arrangements) with the women of Rashi’s family. In this case, it was Simcha’s son Shmuel who married into the Rashi family, wedding a granddaughter of Rashi’s who happened to be the daughter of another star Rashi student, Rabbi Meir ben Shmuel, as well as the sister of Rabbenu Tam and Rashbam. Ri was thus related to Rashi, and his famous grandsons, and one of Rashi’s leading pupils (and best-selling author). This made Ri medieval French-Jewish royalty, so to speak (like, of the Crown of Torah).

All of this might have gone to a young Ri’s head, but it didn't. Whereas his illustrious forbears tended to display a pious humility alongside fierce, argumentative self-assurance, Ri was all honey, no sting. After serving for many years as an assistant to his teacher (and uncle) Rabbenu Tam in Ramerupt, Ri moved on to Dampierre,3 but continued to regard himself as subordinate to Rabbenu Tam, resolutely following his rulings.

However, in the questions he asks on the Talmud and the resolutions he suggests, Ri reveals himself to be a highly creative thinker and a major contributor to the dialectics of Tosafot. His questions and answers were integrated by the generations that followed him in the later twelfth and early thirteenth centuries into their more heavily edited, composite Tosafot. Yet Ri appears on virtually every daf (folio page) of our Talmud.

Inside Ri’s Yeshiva

We have two fascinating (though non-contemporaenous) testimonies about Ri’s role in the formation of the Tosafot as we know them. The first comes from Tzedah la-Derech (“Provisions for the Journey”), a law code crafted with genteel, preoccupied baalei batim (householders, i.e. not professional scholars) in mind. It was written in the mid-1300s in Toledo, Spain by R. Menachem Ibn Zerach, the son of French refugees who himself suffered an outsized amount of violence and persecution even by the standards of the medieval world. R. Menachem’s Tzedah la-Derech includes a robust introduction that contains important historical information about his experiences, as well as other elements of recent history, including the following account of study in Ri’s beit midrash:

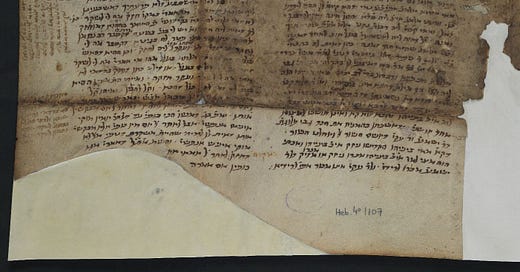

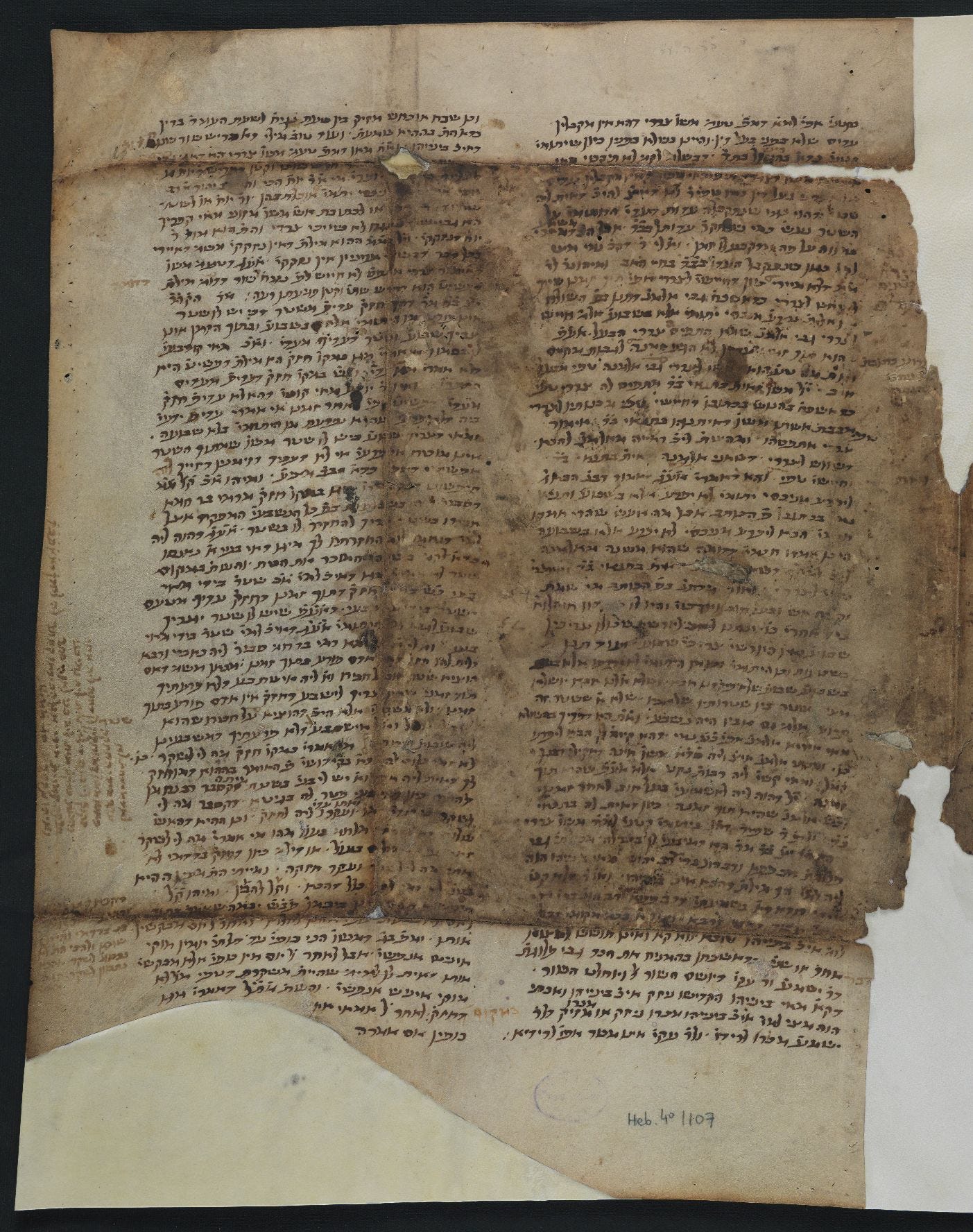

ורבינו יצחק בן אחותו של רבינו תם הנודע בעל התוספות אשר למד ולחמד בישיבה. כי העידו לי רבותי הצרפתים בשם רבותם כי נודע ונתפרסם שלא היו לומדים ופניו ס’ רבנים שכל א’ מהם היה שומע ההלכה שהיה מגיד גם היה לומד כל אחד לבדו מסכתא שלא היה לומד חברו והיו חוזרים על פה ולא היה מגיד רבינו יצחק הלכה שלא היה בפיהם בין כלם כל הגמ’ בין עיניהם כאותה הגדה עד שנתבררו להם כל ספיקות שבגמ’. וכל הלכה ומאמר תנא או אמורא שנראה הפך או סתירה במקום אחר ישב ותקן על אופנו כאשר מבואר לכל מי שראה תוספותם ושאלותם ומשובותם ופירושם וההשגות שהשיגו על זקנם רבינו שלמה.

“Rabbi Yitzchak the son of the renowned Rabbenu Tam’s sister was the composer of the Tosafot which he learned and taught in his yeshiva. My French rabbinic colleagues informed me in the name of their teachers that it was well-known that they would learn from sixty gathered scholars, each of whom would hear the halacha (law) that the others would say. In addition, each would learn thoroughly a single tractate that his peers had not studied, and they would review them orally. Our Rabbi Yitzchak [Ri] would not repeat any law that was not transmitted by them. Among them, the entire Gemara was before them as one text, until each and every question that arose from the Gemara had been settled for them. And each halacha and saying of a Tanna or Amora which seems opposing or contradictory in another place, they would settle and explain according to its context such that it would be clear to anyone who saw their Tosafot, with their questions, responses, explanations, and hassagot (critical notes) which they made on [the teachings of] their elder, Rabbenu Shlomo.”

Menachem Ibn Zerach, Tzedah la-Derech, Introduction

According to R. Menachem, Ri played a dual role as faithful transmitter of Rashi’s legacy and analyst of remaining difficulties. Ri accomplished the collation of parallel passages and the difficulties they raised by assigning a different tractate to each student-scholar. Each would master their designated tractate and then present it before the others, who gathered for the purpose. The entirety of the text at their joint disposal, the Ri would then identify questions and resolve apparent contradictions in the Talmud text. Ri’s resolutions formed the substance of “his” Tosafot, i.e. the Tosafot of his yeshiva. Whether or not the exact figure of sixty scholars is to be taken literally, R. Menachem’s account shows that the academies of the Tosafists were large, organized operations with their own methods of study.

In contrast, the second account of the Tosafistic method, by Maharshal, is content to let the Tosafot live and breathe as tangled texts without all contradictions resolved, an inevitability of the many hands that worked on them. Written in the sixteenth century, Maharshal’s account is not as focused on Ri, but still places him at the center of the enterprise:

בעלי התו' בעצמן חולקים בכמה מקומות, ודבריהם סותרין זה לזה, בסיבה שבמקום אחד הוא דברי ר"ת, ובמקום השני הוא דברי ר"י ור"יבא ויתר החולקים, ומשום הכי במקום א' תמצא תימה וכולה בקושיא, ובמקום השני תמצא מתורץ, והוסיפו ושנו במקומות שונים בגמרא, שבעלי התוספות תלמידי ר"ת היו לרוב, כי שמונים בעלי תו' היו בפרק אחד לפני ר"ת, וכל אחד הגיע להוראה, כגון ה"ר חיים כ"ץ, ור"א ממינץ, וה"ר שמשון משנ"ץ וחביריו, ותלמידים לרוב בלי מספר.

ים של שלמה מסכת חולין הקדמה

“The Tosafists themselves disagree in several places, and their words contradict one another. This is because in one place these are the words of Rabbenu Tam, and in another place they are the words of Ri and others who disagree. For this reason in one place you will find “You might say…” and all that follows is a difficulty, whereas in another place you will find it resolved, because they continued to teach about different parts of the Gemara. The majority of the Tosafists, however, were the students of Rabbenu Tam, since there were eighty Tosafists in a single chapter that was before Rabbenu Tam, each of whom gave rulings, for example Rabbi Chaim Katz, and Rabbi E[liezer] of Mainz, and Rabbi Shimshon of Sens and his colleagues, and a multiude of students too numerous to recount.”

Maharshal, Yam Shel Shlomo, Introduction to Chullin

The (completely fascinating) purpose of Yam Shel Shlomo is to resist the codificatory impulse: that is, to allow halacha and the halachic process to stay messy and undetermined. Halacha, argues Maharshal, is too big to be contained in any one set of rulings, constitutionally incapable of being liberated from the gnarly conversations in which legal culture is embedded. Writing in an era of codification—even among Ashkenazim—Maharshal pointedly emphasizes the multitudinous nature of the Tosafist enterprise. His presentation, interestingly, pits Ri against his teacher, Rabbenu Tam, as well Ri’s student R. Shimshon, the editor of the Tosafot of Sens. The larger point of Maharshal’s account is that each school of Tosafists contributed a different tradition of understanding the text, with Ri headlining one of these schools.

Between Ri and Us

Early printings of the Talmud established the standard form of the page that we still have today, with Rashi and Tosafot flanking the text. In selecting which manuscripts of Tosafot to print, “our Tosafot” were effectively crafted by their first printers. Largely based on Tosafot Tuch (“of Touques,” a city in northern France), which in turn rely upon Tosafot Shantz (“of Sens”), “our Tosafot” lean heavily towards the lineage of both Ri and Rabbenu Tam. And so, our gentle giant appears on nearly every folio page of the printed Talmud, mediated through generations of students’ notes, interpolations, smoothed edges, and other edits.

Just when we think we’ve mastered the sugya, we turn to Ri and see that the matter is much more complicated than we thought. And we are momentarily transported to Dampierre, where we sit at the feet of our master, drinking in his Torah, turning over his questions in our minds, finally stunned and comforted by the smartness of the resolution.

Tosafot Reads

If you’re just getting started with Tosafot, an indispensable handbook is R. Haim Perlmutter’s Tools for Tosafot. It’s sort of like Frank but for Tosafot. My one caveat about this book (like Frank’s) is that I don’t think Gemara or Tosafot, as technical as they are, are quite as mechanistic as it can sometimes seem from the handbooks. In other words, you don’t have to memorize rules in order to understand Tosafot, you just have to get your bearings and jump in and be a careful reader. (The link above is to Seforim Center; Tools for Tosafot is available on Amazon too but at an inflated price.)

A great read on how our Talmud came together is Dr. Edward Fram’s article in the book Printing the Talmud, which you can download freely here.

If you’re still hankering for more on the complex process of creating and transmitting “our Tosafot,” I highly recommend the series of excellent articles by R. Aryeh Leibowitz in Hakirah vols. 15, 18, 20, and 29. Start here.

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

Jastrow is ostensibly (and officially) a Dictionary of the Targumim, Talmud Bavli, Talmud Yerushalmi and Midrashic Literature. However, it’s much more than that; it’s really a key resource for rabbinic and medieval Hebrew as well. Though I prefer using an Aramaic-Hebrew dictionary generally, I still use Jastrow occasionally for the wealth of information in each entry. There are now excellent online and app options for using Jastrow. It’s on Sefaria, as well as searchable on this website, which will display a copy of the physical page. TES, the Jewish software company that distributes the likes of Bar Ilan and Otzar Hachochma, has a paid app called Talmud Dictionary that is actually Jastrow, app-ified (Android | Apple).

Ri Twitter Threads

The Ri Twitter thread is here:

A while back, I did a thread about the transmission of Tosafot and the creation of “our” Tosafot. You can read it here:

On Deck

Next week, we’re following the trail of Tosafistic learning out of France into Germany and Bohemia (today in the Czech Republic and Austria), hot on the trail of R. Yitzchak Or Zarua. We’ll eventually head over to the Sefarad to catch up with what’s happening in Talmud commentary over in north Africa while all this is going down in Ashkenaz.

Thoughts? Feedback? Special Requests?

We do not know with precision Ri’s date of birth, though he must have been at a generational remove from Rabbenu Tam, who was born c. 1100. Ri lived until c. 1185, some fifteen years after the death of Rabbenu Tam.

Vitry-en-Perthois, near Rashi’s hometown of Troyes; there are a bunch of other Vitrys in France, as per usual for French place names.

Same thing goes for Dampierre; there are several, but this on is in Aube in the Champagne region where Ramerupt, Vitry, and Troyes were also located.