When Yehuda ha-Levi Brought his Heart to the East

🗺️ In today's newsletter, we explore a few texts that give us a closer look at R. Yehuda ha-Levi's journey, both physical and spiritual, to the Land of Israel.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. We’re at the tail end of a series on premodern travel to Eretz Yisrael, with two illustrious olim (“ascenders,” those who come to live in Israel) to round out the series: R. Yehuda ha-Levi, whose journey we’ll explore today, and then the great Ramban.

I’ve just returned from a somewhat epic road trip from here in Los Angeles to New Orleans, the reason for my brief hiatus, and wanted to share with you a few historical finds I made along the way:

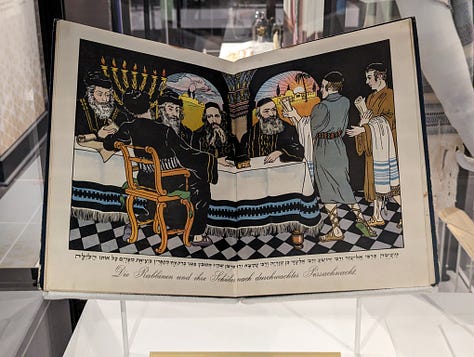

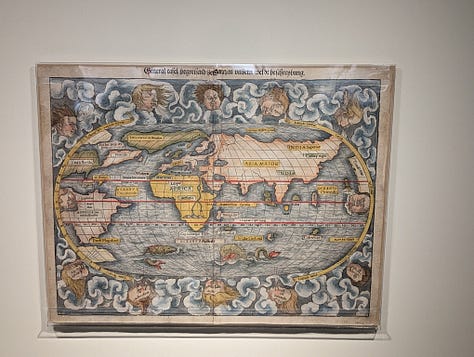

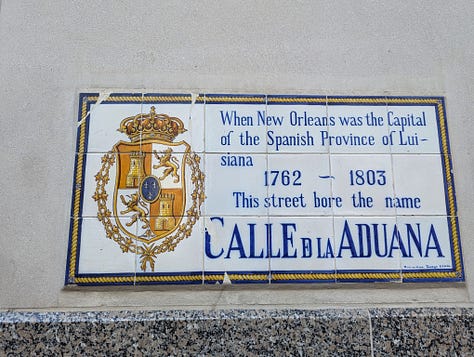

On the left is one of my very favorite Haggadah illustrations, depicting the Rambam, Rashi, Tur, Bet Yosef, and the Rif as the five rabbis in Bnei Brak. It’s from the Josef Schlesinger Haggadah, published in Budapest c. 1927/8, a copy of which we found at The Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience in New Orleans. So, modern, but also a little medieval! Next, in the center, is a map made by the German cartographer (and Christian Hebraist) Sebastian Munster. The map in the picture dates from 1545 and is at the The Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin; it’s based, however, on a map made in 1540, less than fifty years after the European discovery of the Americas. It is largely made according to early travelers’ accounts. I didn’t get any good pictures of the few eighteenth-century French colonial buildings in the French Quarter because we saw them during a nighttime walking tour, but all over the Quarter there are signs from the Spanish period with the street’s erstwhile Spanish name, like the one on the right. Which brings us right up to the boundary between early modernity and “our” modernity.

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here (and an archive of all audio editions here.)

In this issue:

“My heart is in the east,” wrote R. Yehuda ha-Levi, “and I am at the far edge of the west” (לִבִּי בְמִזְרָח וְאָנֹכִי בְּסוֹף מַעֲרָב). This plaintive line has echoed across centuries, a cri de coeur of many a Jew who feels the ache of prolonged exile. (You can even buy a throw pillow embellished with the line of poetry on Etsy.) We have seen that many Jews in the medieval and early modern periods heeded this call of the heart and visited, or settled in, the Land of Israel, to the extent possible given political and economic conditions. Some even recorded their experiences in verse as did Yehuda ha-Levi, namely, Yehuda ha-Harizi. None, however, can lay claim to the intense spiritual trajectory and extensive literary documentation that Yehuda ha-Levi’s journey involved.

A Journey to the Journey: The Genesis of Yehuda ha-Levi’s Aliyah

In my first newsletter devoted to R. Yehuda ha-Levi, I covered the background to his journey to Eretz Yisrael, concentrating on the life he left behind. Here, I’ll briefly recount his life in Spain. Ha-Levi was born in Tudela (or perhaps Toledo) right around 1085, the year that the latter changed hands between the Muslims and the Christians. It was a decisive event in the Christian mission to grasp control of Spain, most of which had not been in Christian hands since the Visigothic period in the early Middle Ages. The city into which Yehuda ha-Levi was born, even if Christian, was culturally Islamicate, and the education he received was typical of Judeo-Arabic Sefardi culture: traditional Jewish texts alongside medicine, philosophy, and literature. He was a master of Biblical idiom, which he was to employ not only with dazzling skill but also with evident relish in his poetry.

By the time he set sail from Spain to Egypt, bound for the Land of Israel, R. Yehuda ha-Levi was a celebrated man of letters who had arisen as a young prodigy and continued to climb the social and cultural ranks of Sefardi Jewry to the very top. His renown is central to his story, for his act of renouncing worldly success meant turning his back on the very culture he’d come to exemplify. Though clearly learned in Torah, R. Yehuda ha-Levi was not functionally a rabbi but a man of letters who rose to communal prominence, becoming involved in various communal activities but supporting himself as a merchant and physician. Sometime in mid-life, Yehuda ha-Levi made the decision to leave behind the wine-parties of Spain he’d captured so evocatively in poetry—and even the Torah learning in Sefarad’s famed yeshivot (academies)—and make his way to the Land of Israel. He set sail in the summer of 1140.

Ha-Levi’s Stay in Alexandria and Cairo

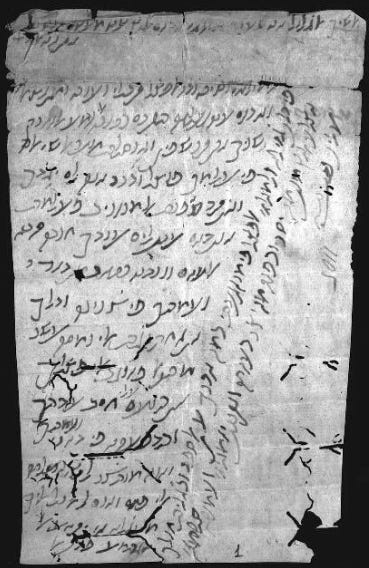

Yehuda ha-Levi’s journey to Israel is particularly well-attested, both conceptually and actually, in his works, including his philosophical masterwork, written in the form of a dialogue, known as Sefer ha-Kuzari (The Book of the Khazarian [King]); a rich trove of letters found in the Cairo geniza, some, like the one at the top of this newsletter, written in ha-Levi’s own hand; and also in his poems, not only in snatches of autobiography but also in their spiritual temper, emotional mood, and poetic expression.

Yehuda ha-Levi wrote a number of poems “on the water,” reflecting—or perhaps anticipating—the experience of sailing the Mediterranean from Spain to Egypt and then to Israel, fraught with dangers, both natural and human, in the twelfth century. Here is a particularly emotive and evocative example:

וְיָם מִתְרוֹצֵץ וְקָדִים יְפוֹצֵץ

אֲרָזִים, וְיָפֵץ רוּחַ קְצָפָיו

שָׁחָה קַרְנָם וְנִבְהַל סַרְנָם

וְנִלְאָה תָרְנָם לִפְרֹשׂ כְּנָפָיו

יִרְתַּח בְּלִי אֵשׁ וְלֵב מִתְיָאֵשׁ

בְּעֵת הִתְבָּאֵשׁ בְּמָשׁוֹט מְנִיפָיו

דַּלִּים מֹשְלָיו וְנִרְפִּים סֹבְלָיו

וּבֹעֲרִים חֹבְלָיו וְעִוְרִים צוֹפָיו

וְהָאֳנִי כְּשִׁכּוֹר יְתַעְתַּע וְיַחְכֹּר

בְּלִי הוֹן יִמְכּוֹר שֹׁכְנִי כְּתֵפָיו

וְזֶה לִוְיָתָן בְּעַד יָם אֵיתָן

יַקְדִּישׁ כְּחָתָן לְמִשְׁתֶּה אֲסוּפָיו

וְיַד אֻקְיָנוֹס תֶּאֱהַב לִכְנוֹס

וְאָבַד מָנוֹס וְאֶפֶס מִבְרָח

דַּלּוּ עֵינַי נֶגְדְּךָ אֲדֹנָי

וְאֶת תַּחֲנוּנַי שַׁי אָשִׁיבָה

אֶחֱרַד לְעִתַּי וְאֶרְגַּז תַּחְתַּי

וְקוֹל בֶּן אֲמִתַּי לְךָ אַקְרִיבָהOcean rushes, crushed, east

wind splits cedars, gale

spits foam. Prow downwards,

boards groan, mast fails

stretched sails. Sea boils

though no fire. Heart despairs

at worthless oarsmen, helpless mates,

lazy porters, brutish rope-men,

blind lookouts. Drunken ocean

toys, mocks, trades folk for no price.

Kraken deep in endless ocean

summons fellow-beasts to feast.

The ocean gladly gathers all.

No place for a man to flee, no refuge!R. Yehuda ha-Levi, from יוֹעֵץ וּמֵקִים בִמְרוֹם שְׁחָקִים, translated by Raymond P. Scheindlin in Song of the Distant Dove (Oxford, 2007), pp. 243-245

R. Yehuda ha-Levi arrived in Alexandria, the major port city of Egypt, in September of 1140. There he was compelled to accept the hospitality of his associate, R. Chalfon ha-Levi (of no relation), much to the chagrin of other elite community members who wished to play host to him. In general, ha-Levi was viewed as a celebrity, which, as he recorded in poetry, gave rise to internal conflict: on the one hand, he wished to pursue a more ascetic, interior form of spiritual life, while on the other, he was accustomed to society life and did not want to insult his hosts. He encountered a similar conundrum in Cairo, which he visited as part of retracing the steps of Bnei Yisrael in the Torah, from slavery in Egypt to the promised Land. Yehuda ha-Levi apparently wished to make way overland to Israel through the desert, as had Bnei Yisrael, but encountered difficulty in securing travel and returned to Alexandria in order to travel by sea to Eretz Yisrael.

Did Yehuda ha-Levi Reach Eretz Yisrael?

Writing some four centuries after Yehuda ha-Levi’s lifetime, R. Gedalya Ibn Yahya recorded in his Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah (The Development of the Tradition), an account of ha-Levi’s death that has endured in collective memory:

כתב ספר יוחסין שרבי יהודה הלוי היה בן נ’ שנה כשהלך לארץ ישראל כנראה בפיוטיו וקבלתי מזקן א’ שבהגיעו אל שערי ירושלים קרע את בגדיו והלך בקרסוליו1 על הארץ לקיים מה שנאמר כי רצו עבדיך את אבניה ואת עפרה יחוננו והיה אומר הקינה שהוא חבר האומרת ציון הלא תשאלי וכו’ וישמעאל א’ לבש קנאה עליו מרוב דבקותו והלך עליו בסוסו וירמסהו וימיתהו.

It is written in the Book of Genealogies [Sefer Yuchasin] that Master Judah Halevi was fifty years old when he went to the Land of Israel, as can be seen from his poems. I have a tradition from a certain elder that when Halevi reached the gates of Jerusalem, he tore his clothes and walked with his knees on the ground to fulfill the scripture: “For Your servants take pleasure in her stones and cherish her soil” [Tehillim 102:15]. He was reciting the lament he had composed, “Jerusalem! Have you no greeting [Tziyon, ha-lo tishali],” when an Arab, observing his fervor, was overcome with religious zeal against him. He bore down on him with his horse, trampled him, and killed him.

R. Gedalya Ibn Yahya, Shalshelet ha-Kabbala, trans. Raymond P. Scheindlin in Song of the Distant Dove, p. 249.

While there is much in this account that cannot be verified and some elements that are highly improbable, there is also, as Dr. Raymond Scheindlin (the translator cited above, and my mentor and teacher) notes, much about it that is doubtlessly true from what Yehuda ha-Levi’s own words tell us. The age of fifty that R. Gedalya cites is taken from ha-Levi’s poem, הֲתִרְדֹּף נַעֲרוּת אַחַר חֲמִשִּׁים. The piety and submission inherent in the dying posture attributed to ha-Levi reflect the ethos of so many of his poems; the emphasis that he placed upon the stones and dust of the Land of Israel is also reflected in R. Gedalya’s account.

In addition, Scheindlin maintains that the evidence we have points almost certainly to Yehuda ha-Levi’s successful aliyah:

Did Halevi fulfill his dream of reaching the Land of Israel, dying there, and mingling his body with its soil? There is no concrete evidence one way or another. But the journey from Alexandria to Acre or Ashkelon, Palestine’s main ports, ordinarily took only about ten days, and since Halevi died in midsummer, as we shall see, there is no reason to doubt that he made the voyage successfully. If he did arrive, he must have sent word to his loyal friend Halfon, and since so many letters to Halfon have been preserved, perhaps someday we will be lucky enough to find one from Halevi confirming his arrival in Palestine.

Raymond P. Scheinlin, Song of the Distant Dove, p. 163.

He goes on to suggest that it is likely that Yehuda ha-Levi went on to visit the holy sites of Chevron (Hebron) and Jerusalem, which could be visited, despite prohibitions on Jewish settlement in the latter at the time that ha-Levi was presumably in the Land of Israel. We can imagine him, finally finding a measure of peace and spiritual fulfillment, seeing the stones of Jerusalem with his own eyes and grasping the sacred earth with his very feet.

Reads and Resources

I know I’ve recommended it before (and cite it a number of times above), but I have to one more time, because it’s such a textually rich and thorough account specifically of Yehuda ha-Levi’s journey to the Land of Israel: The Song of the Distant Dove.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective. If you’d prefer to make a one-time donation in any amount, you can do that easily through my page at Ko-fi. Thank you so much.

Literally, “ankles”—Scheindlin suggests that this is clearly intending to say “knees.”