Coffee with Rashba

☕ The cantankerous Torah giant of Barcelona was involved in all of his day's affairs, walking a middle path that was informed by, but also wary of, Rambam's complex philosophical legacy.

Hello, dear readers, and welcome to new subscribers. A quick note of gratitude to all who have pledged to support my work! Thank you so much. It’s an exciting prospect in that it will allow me to devote more time to writing for you. I am considering different ways of adding content and optional upgrades, and remain committed to keeping this main newsletter free and accessible to all.

Okay, so I got a little tangled up in our timeline last newsletter: I remembered Ran being closer in time to Ramban’s beit midrash than he actually is. We’ll definitely get to Ran, but first we have a full roster of Ramban’s colleagues and students to spend time with. So today, we’re hanging out with the great Rashba.

Inside this issue:

The Decider

R. Shlomo Ibn Adret (Rashba) would have made every one of Sefarad’s “36 under 36” style lists. By the age of forty, he was the undisputed decisor not only of his native Catalunya (the northeast of Spain) but of a far wider swath of the Jewish world, exerting his influence as far as Egypt and Bohemia. Born to a well-heeled Barcelona family c. 1235, Rashba’s principal teacher, by his account, was Rabbenu Yonah Gerondi. He was also educated in Ramban’s yeshiva and accounted one of the master’s foremost students. While a young man, Rashba’s financial services made him something of a power broker: the king of Aragon himself took out a loans from Rashba. (It’s not available for sharing, but you can see an autograph of Rashba’s from the Archive of the Cathedral of Barcelona, here.) Having made his fortune early in life, Rashba was able to turn towards communal activities and Torah for the majority of his time.

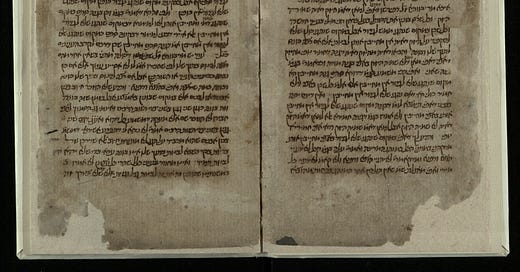

Rashba wrote a copious amount of teshuvot (responsa), or, in any case, an unusually large number of his responsa have been preserved. These have been messily published and require some textual care to handle, especially given their historic and halachic significance. (For example, the volumes known as “one” and “two” do not necessarily contain earlier letters, and some volumes contain a mixture of responsa by different rabbis.) One of the interesting features of Rashba’s responsa are the great number that deal with communal controversies in public affairs and those that address theological matters.

Another factor that arises from his letters is that Rashba was ineluctably pressed into service by King Pedro III of Aragon as an adjudicator of difficult lawsuits. Despite his reluctance to get involved in certain high-profile cases—he once sought the imprimatur of Maharam of Rothenburg in a particularly thorny appeal—Rashba’s desire to keep Jewish affairs in the batei din (Jewish courts) rather than the royal or municipal courts inspired his deep involvement.

The Halachic Master

Rashba is known for his Chiddushim on the Talmud (the technical translation of this term is novellae, which is not so helpful: it means, roughly, “insights”). Constructed, it seems, out of his lecture notes for the students in his yeshiva, Rashba’s Chiddushim cover the core “teaching texts” of Sefardi yeshivot. They build upon the integratory style of the Ramban, who introduced in his own Chiddushim a synthesis of Tosafist dialectics (back-and-forth analytical debate) and the Sefardi interest in resolving a sugya (unit of Talmud) down to its practical application. An apotheosis of this synthetic method, Rashba’s comments remain a mainstay of yeshiva learning down to our times.

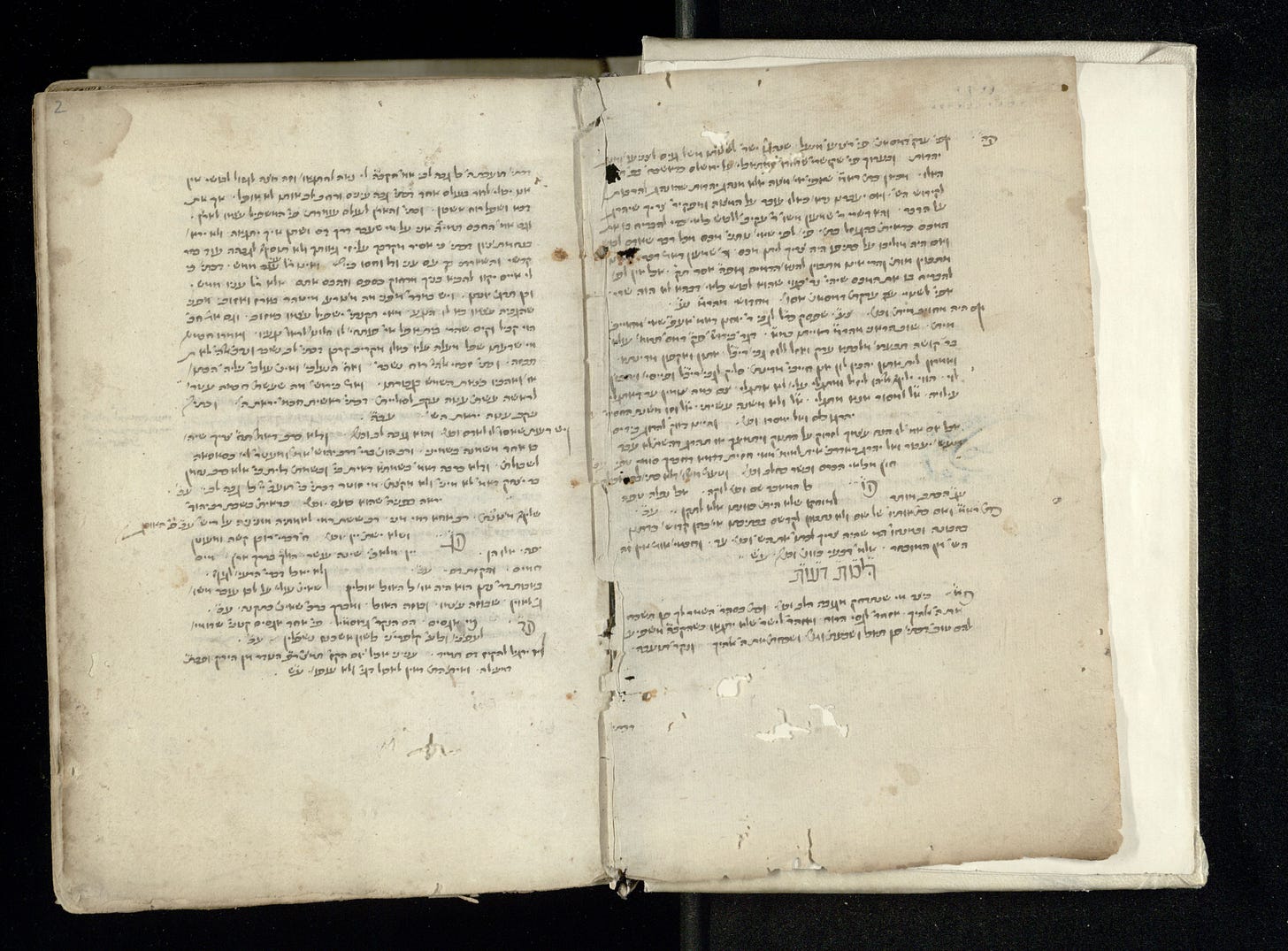

Like his mentors before him, Rashba too wrote books devoted to specific areas of halacha. The most extensive and celebrated of these is Torat ha-Bayit (“Laws of the Home”), which treats everyday areas of ritual law, including kashrut and niddah. Though written with Rashba’s trademark clarity, Torat ha-Bayit was comprehensive and detailed, spurring him to write his own abridgement of it, titled Torat ha-Bayit ha-Katzar, “the abridged.” (Consequently, the full-length version is now known as Torat ha-Bayit ha-Aroch, “the full.”) Rashba’s Barcelonan colleague and personal friend R. Avraham ha-Levi (Ra’ah) wrote a series of critical glosses (hassagot) on it titled Bedek ha-Bayit. Rashba’s strength of conviction and take-no-prisoners personality is evident to the reader of his responsa, but it takes a particularly cantankerous turn now: in response, Rashba disseminated an anonymous defense of Bedek ha-Bayit titled Mishmeret ha-Bayit, a play on Ra’ah’s title, “Checking the Home,” in the form of “Protecting the Home.” In a later responsum, Rashba revealed himself as the anonymous author of Mishmeret ha-Bayit.

A Middle Path Between (External) Philosophy and (Internal) Kabbalah

Rashba also carefully gave his attention to the aggadic (narrative and non-legal) portions of the Talmud. His Chiddushei Aggadot ha-Shas did not garner wide circulation, but they have been published from manuscript (Jerusalem, 1966). Despite Rashba’s distaste for allegorical interpretation of scripture, which had become popular and powerful in his day, here Rashba was willing to use Rambam’s non-literal interpretive method from the Moreh ha-Nevuchim (Guide of the Perplexed). (Allegorical interpretation suggests that certain parts of the Torah were symbolic or otherwise non-literal, i.e., they did not happen literally as written but represent ideas.)

From scattered hints among his writings, it emerges that Rashba was initiated in the Kabbalah of his teacher, Ramban. However, he remained even more reticent than Ramban in revealing his knowledge. At the same time, Rashba was well-versed and comfortable in the philosophic culture prevalent in Spain and Provence in the thirteenth century and into the fourteenth. This would seem to make him a curious ally for the controversialist Abba-Mari ha-Yarchi of Montpellier to seek out in his attempt to enact a ban against the study of philosophy.

In actuality, neither Rashba nor Abba-Mari was an extremist; Rashba in particular emerges as a moderate voice. On the one hand, Rashba presided over the passage of a ban (cherem) in Barcelona against the study of non-Jewish philosophy by persons less than twenty-five years of age. On the other hand, Rashba exempted all Jewish philosophy from the ban (in particular, Rambam’s Moreh) and permitted study of medicine and astronomy without restriction. In Provence, a more stringent measure was sought, but ultimately trounced by the greater troubles of the French general expulsion of Jews in 1306.

Rashba involved himself in theological debates in other formats as well. He was active in resisting the efforts of the mendicant friars to convert Jews through the methods of scholastic debate. Rashba wrote explicitly against Ramon Martí (Raymond Martini), whose Pugio fidei (“Dagger of Faith”) was the most well-developed conversionary manual to come out of the thirteenth century, arguably the Middle Ages. We know that Rashba was himself involved in public debate with Christians. Also, interestingly, Rashba wrote a treatise, known as Ma’amar Yishmael, refuting the claims of the prominent eleventh-century Muslim philosopher Ibn Ḥazm against Judaism. This demonstrates Rashba’s keen interest in defending the basic tenets of Jewish tradition as well as the continued valence of Judeo-Arabic culture in Sefarad.

When Rashba passed away c. 1310, he had overseen, and been a major contributor to, one of the most vibrant, yet portentous, periods of Sefardi history.

Rashba Reads

Sefaria has a good selection of Rashba’s works, though untranslated, including not only his Chiddushim but also both versions of Torat ha-Mayit, Mishmeret ha-Bayit, and three other important halachic works (on mikvaot, challah, and Shabbat and chaggim). The responsa are not complete there.

A version of of Ma’amar Yishmael also appears on Sefaria; it looks to be based on the 1863 publication of Joseph Perles from a no-longer-extant manuscript, though I’m not certain. Betzalel Naor has a new critical edition based in part on Perles’ work. You can read a review of it here on the Seforim Blog.

An absolute classic for entering the world of Rashba and his thirteenth-century colleagues is Dr. Bernard Septimus’ Piety and Power in Thirteenth Century Catalonia.

Jewish Learning Resource of the Week

I’ve already shared online resources for Aramaic-English translation (based on Jastrow’s classic more-than-a-dictionary), but today I want to highlight a resource for Aramaic-Hebrew translation: The Daf Yomi Portal’s dictionary feature. I find the shorter distance between Aramaic and Hebrew a boon to remembering Aramaic vocab, so this tool has been a gamechanger for me. There’s also a companion app (Android | Apple) which is now one-tap to access the dictionary. (If you prefer translation into English, give the resources in the first link above a try.)

Rashba on Twitter

Next Coffee Date

Next week we take a mystical-pietistic turn to spend time with Rabbenu Bachya ben Asher.

Great blog!

What you neglect to mention is the Rashba's overarching influence on future generations. The Bais Yosef considered his responsa to be very authoritative and quotes them extensively - probably more so than any other source. Also, his novellae on the Talmud are written extremely clearly - much more so than most other Rishonim - and are therefore the number one go-to for any Talmudic student (after, of course, the French commentaries of Rashi and Tosfos).

He is likely in the list of the most influential Rishonim of all time.