Manuscripts of the Siddur and Machzor

📜 The Jewish prayerbook is ubiquitous—but it wasn't always that way. Today we examine early examples of the siddur and machzor, as well as some remarkable illuminated manuscripts.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. The siddur (daily prayerbook) and machzor (holiday prayerbook) are an elemental part of Jewish book culture, with an array of rites (nuschaot) available to us today—and many more “lost” rites waiting to be rediscovered in manuscript. In spite of this diversity and, today, ubiquity, possessing a written prayerbook was a luxury before the advent of printing. Being that it is one of the most common forms of Hebrew manuscript, we won’t be able to review the full panoply of extant texts; instead, we’ll take a look at the early appearances of the siddur in manuscript and then turn to some special illuminated examples.

In this issue:

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here (and an archive of all audio editions here.)

The First Siddurim: Seder Amram Gaon and the Siddur of Rasag (Saadia Gaon)

The privilege of sliding into one’s seat at shul (synagogue) and grabbing the nearest complete copy of the order of the prayers is lost on us moderns: it is a book to be, at critical moments, kissed by our lips, but nevertheless a common object in our worlds. In the 9th century, the very act of writing down the order (seder, later siddur) of the prayers was entirely novel, prompted by the requests of far-flung Jewish communities sent to the great academies of Bavel, today’s Iraq. Rav Amram, gaon of Sura, was asked by the community of Barcelona to enumerate the daily, weekly, and yearly cycle of prayers. Rav Amram began his reply by noting that his illustrious predecessor, Rav Natronai Gaon, had received a similar request from Lucena, Spain, regarding the appropriate means of saying the rabbinically required one hundred blessings a day. However, Rav Natronai had not written out a complete seder of tefillot, which Rav Amram presently set out to do. His finished seder included, as with most such early enumerations, the full cycle of prayers, including an early version of the Passover haggada.

A bit less than a century later, the famed, fiery R. Saadia Gaon also composed a Siddur in a similar style, which included his own piyutim (liturgical poems) and a commentary in Judeo-Arabic. These two gaonic siddurim are of profound importance for the development of our prayerbook. As Rabbenu Tam wrote:

וכל שאינו בקי בסדר רב עמרם גאון ובהלכות גדולות ובמס’ סופרים ובפרקי דר’ אליעזר ובתלמוד ובשאר ספרי אגדה אין לו להרוס דברי הקדמונים ומנהגם, כי יש עליהם לסמוך בדברים שאינם מכחישין תלמוד שלנו אלא שמוסיפין. והרבה מנהגים בידנו על פיהם.

Anyone who is not proficient in Seder Amram Gaon and in Halachot Gedolot, in Masechet Sofrim and Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, the Talmud and the other books of aggada, does not have grounds to do away the words of our predecessors and their practices, because we have on whom to rely in all things that do not contradict our Talmud but rather add to it. Indeed we have many practices in our hands that derive from their mouths.

Rabbenu Tam, Sefer ha-Yashar, Responsa section, 45, par. 3 [p. 81 in the Berlin 1898 edition].

However, we have only relatively poor textual witnesses of Seder Amram Gaon, not because it wasn’t widely circulated, but because it is an early text that was frequently reworked. Happily, the eminent liturgical historian Daniel Goldschmidt created a critical edition of Rav Amram which has been published by Mosad ha-Rav Kook (Jerusalem, 1971). You can also find the Jerusalem 1912 edition of Rav Amram by Aryeh Leib Frumkin on HebrewBooks.org (Part 1 and Part 2). For Rasag’s Siddur, we have Bodleian Library, Oxford Ms. Hunt. 448, which has not been digitized. There is a good edition of Rasag by the scholars Israel Davidson, Simcha Asaf, and Issachar Yoel (Jerusalem, 1963).

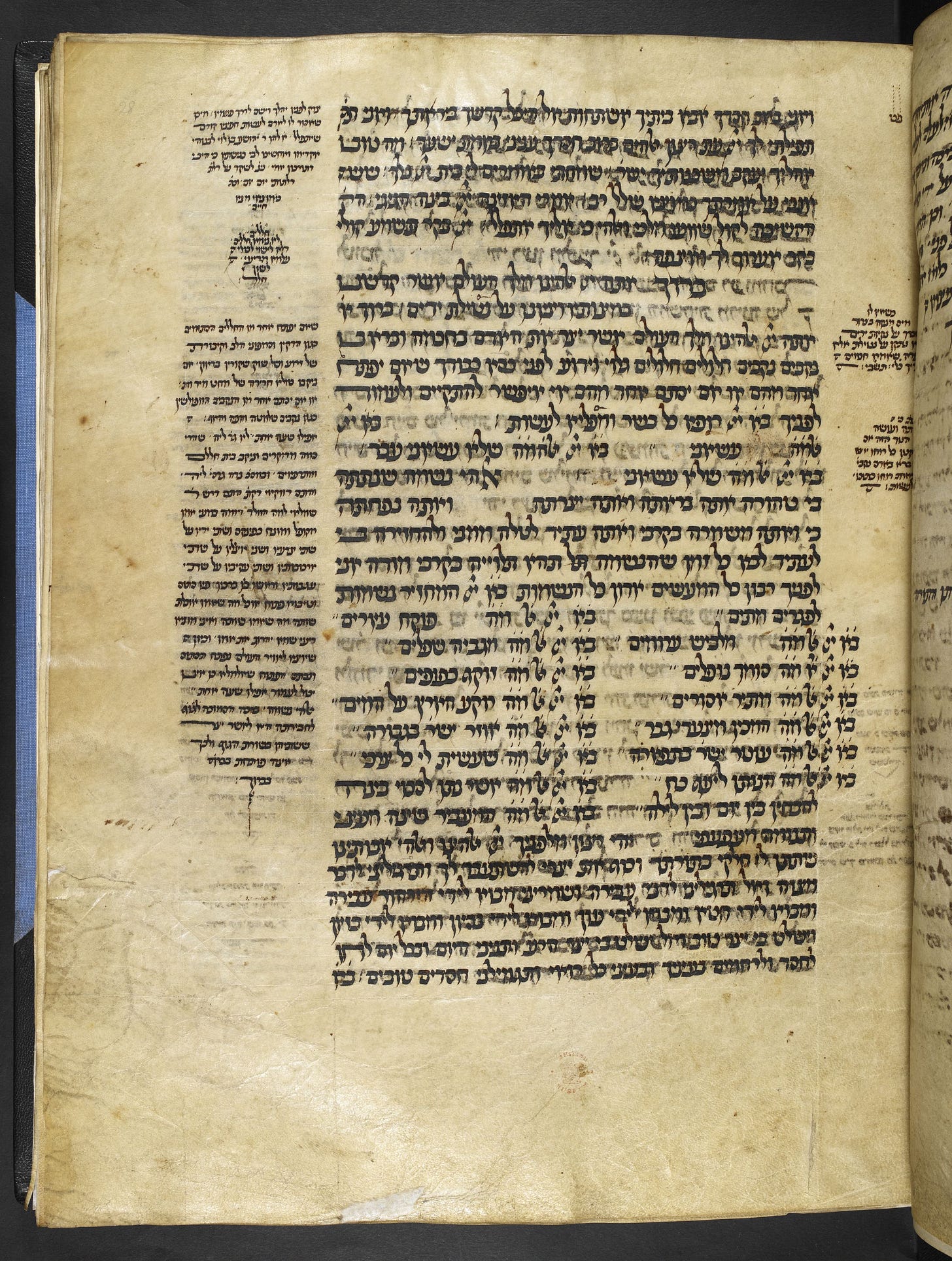

The Function of a Medieval Machzor: A Look at Machzor Vitry

An expanded form of the project begun by Rav Amram and Rasag is evidenced in Machzor Vitry, which includes not only the cycle of prayers for weekdays, Shabbatot, and holidays, but also numerous halachot (laws) related to matters at hand for each liturgical occasion and time of year. Machzor Vitry also contains “everyday” laws such as laws of the wedding ceremony and of kosher slaughter. Written by R. Simcha ben Shmuel (c. 1070–1105) of Vitry, a town in northern France for which the composition came to be named, it is one of the important halachic works produced by the school of Rashi. (R. Simcha was a student and then colleague of Rashi’s; his son married Rashi’s daughter, and his grandson was the Ri (R. Yitzchak of Dampierre), chief architect of the Tosafot.) Which is to say, a machzor in the Middle Ages was not merely a means of reciting the prayers correctly, but a guidebook to the Jewish year.

Machzor Vitry, like many Ashkenazi books, is extant in numerous variants, since it was reconfigured and updated, as was the custom in Ashkenaz. There are eleven substantially complete manuscript versions of it from the medieval period, each somewhat different. Pictured above is the basis for the print edition, which includes an anonymous commentary.

Illuminated Machzorim

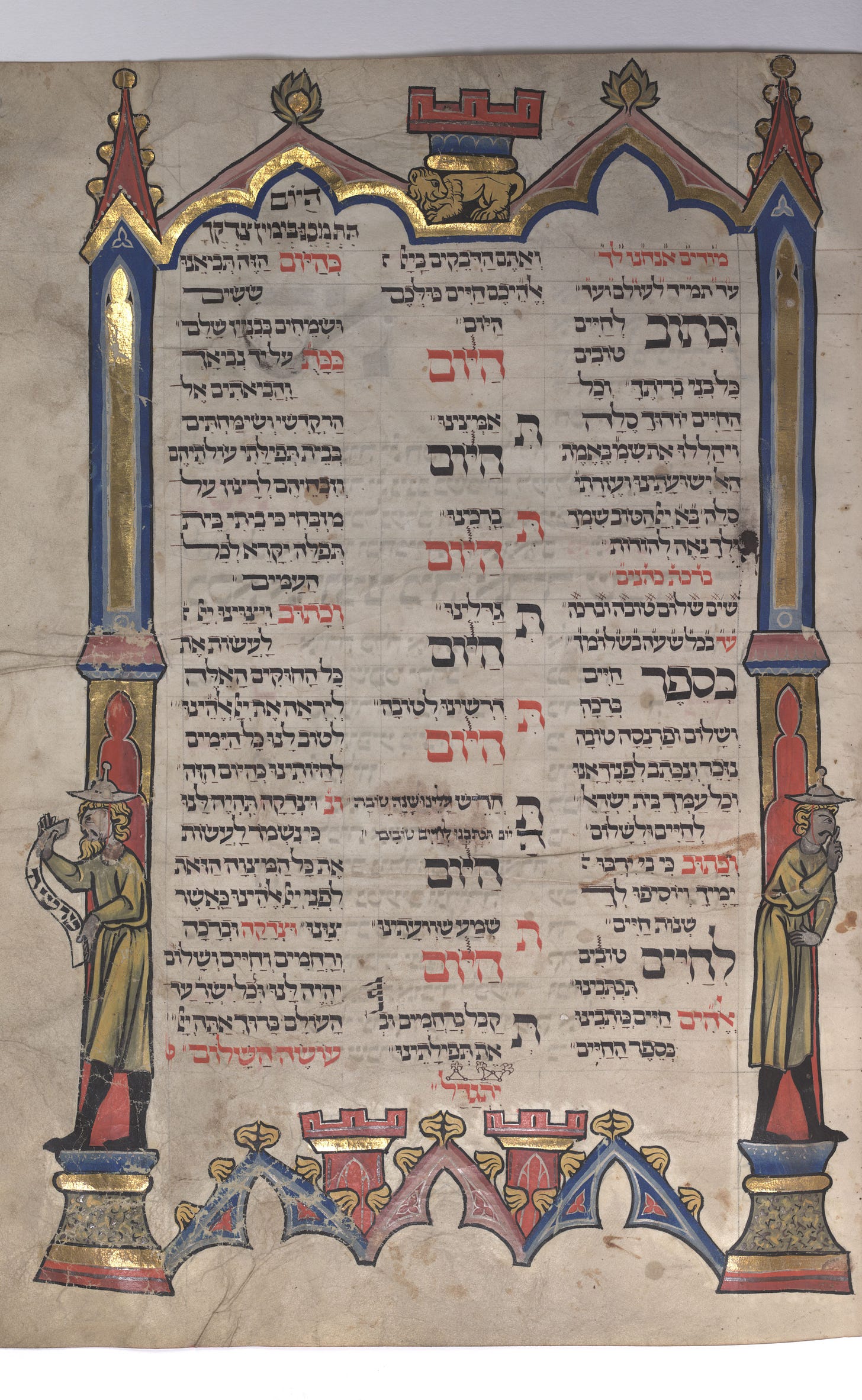

Beginning around the 13th century, we begin to see beautifully scribed and illuminated machzorim produced in Ashkenaz and Italy. These luxury items are some of the most iconic material objects to come out of the Jewish Middle Ages; their fame has garnered them the names for which they are known. (Less famous Hebrew manuscripts are known more technically by their shelfmarks.) It appears that their patron would have allowed them to be used in shul during holidays, in service of the community. Though not an exhaustive list, I’ve aimed below to give you a glimpse into some of the best-loved.

The Michael Machzor

Dating from 1258, making it one of the earliest illuminated Hebrew prayerbooks, the “Michael Machzor” bears the curious distinction of boasting an upside-down image. It is likely that this image was produced by a non-Jewish illustrator, who, unfamiliar with Hebrew, flipped the book as though it were a Latin volume opening from left to right. Nevertheless, as noted by scholars, the images show evidence of having been produced in dialogue with the Jewish scribe, one Yehuda ben Shmuel, or perhaps the patron of the book. The illustrations also seem to have influenced the production of later volumes in this cultural arena.

The Amsterdam Machzor

Another early manuscript, also dating to the 1250s, is the “Amsterdam Machzor,” currently on joint viewership in either Amsterdam or Cologne, near where it originated. Notably, the scribe appears to have written the text and the initial letters, while two hands illustrated and yet another added the gold leaf, somewhat less precisely.

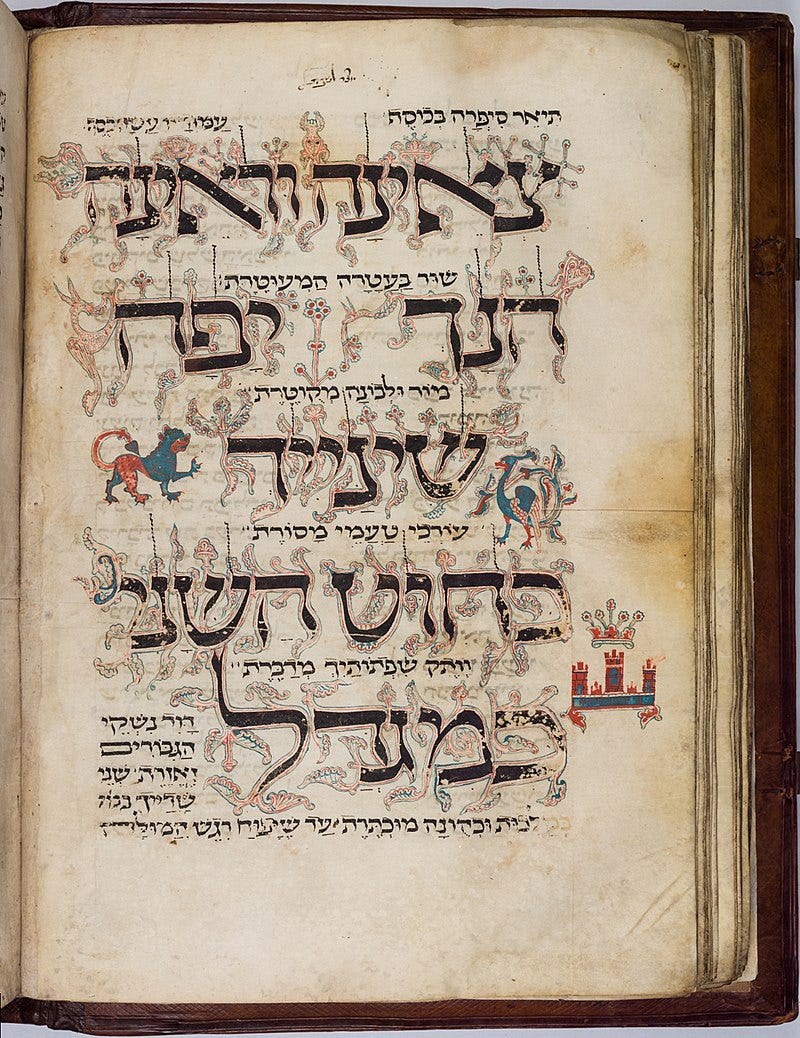

The Worms Machzor

This extraordinary machzor was in use in Worms, Germany from the 13th century until Kristallnacht in November 1938. (Yes, you read that right, six and half centuries of use. After some legal proceedings, it finally landed in Jerusalem in 1957.) However, it is comprised of two volumes that were not originally created together, but were later united, the first dated 1272 and the second thought to date c. 1280. Volume 1, which includes prayers and many piyutim for the four special Shabbatot, Purim, Pesach, Shavuot, and Tisha be-Av, is vowelized according to an obscure Eretz-Yisrael tradition. The Worms Machzor also, importantly, contains the oldest dated evidence of the Yiddish language. Also: click over and see this series of Israeli stamps featuring the Worms Machzor, they’re adorable.

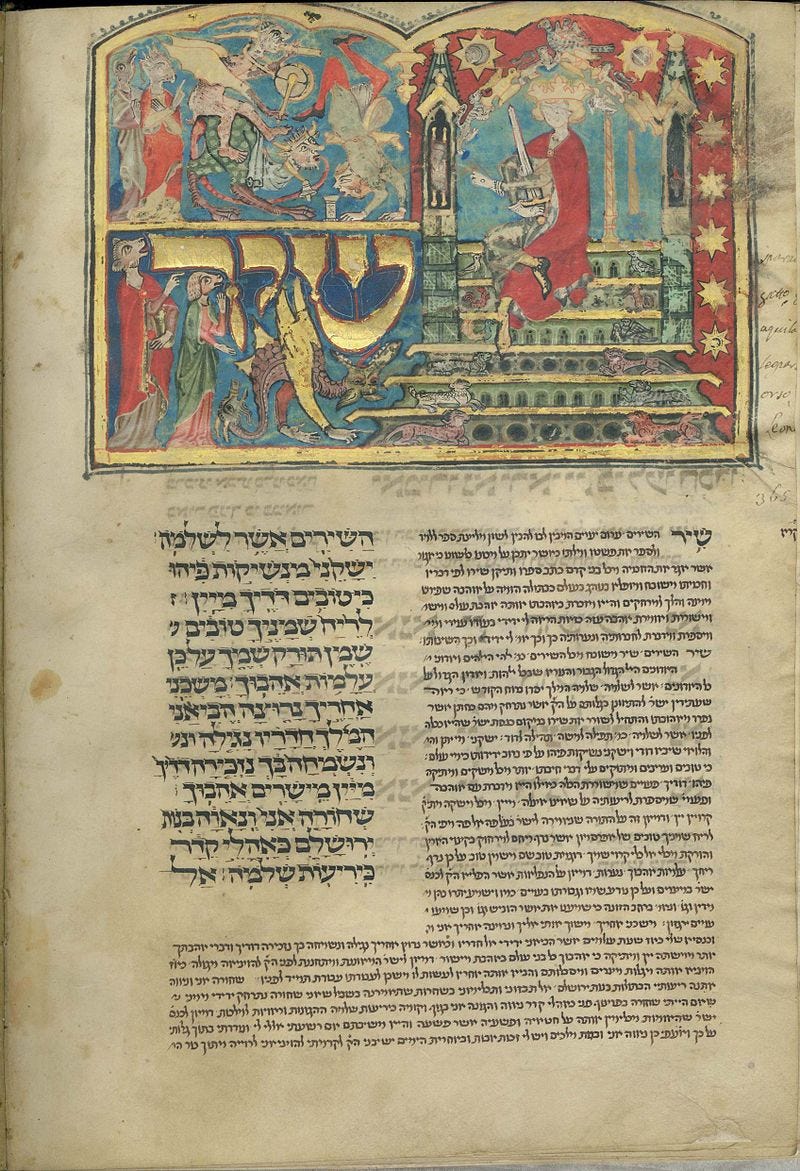

The Tripartite Machzor

This manuscript’s moniker derives from its three parts, which, a common story for such precious objects, was divided among owners. Significantly, this manuscript, written in southern Germany c. 1320, exhibits illustrations of some humans with animal heads, namely, the women. We’ll take a closer look at this phenomenon next week when we examine the Birds’ Head Haggada. Originally covering the whole year’s liturgical cycle, today’s volume 1 is Kaufmann Ms. A 384, now at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest; volume 2 is British Library, London Ms. Add. 22413; and volume 3 is Bodl., Oxford Ms. Mich. 619 (not to be confused with the Michael Machzor, above).

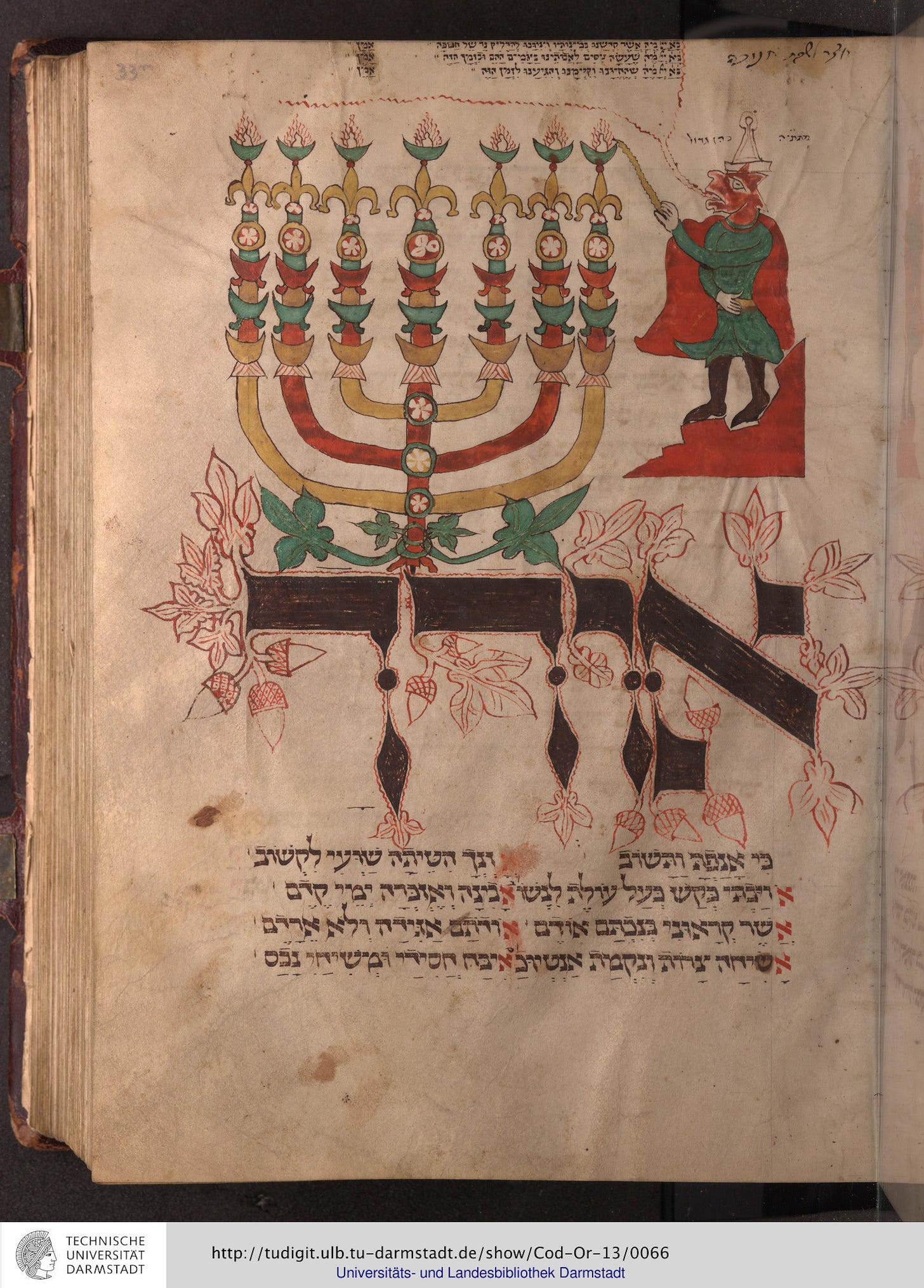

The Esslingen Machzor

I love this one so: its black, white, and red decoration is both minimalist and ornate all at the same time. Produced in 1290 by Kalonymos ben Yehuda, it is a “winter machzor” for Rosh Hashana, Yom Kippur, and Sukkot, and has been identified as the (or one of the?) missing parts of a larger manuscript, the other part of which is Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana Ms. Ros. 609. Whether it was part of a larger composition covering the whole year remains conjectural. It also seems closely related to the early 13th-century “Double Machzor”—its constituent parts also known separately as the “Dresden Machzor” (Sächsische Landesbibliothek Ms. A 46a)1 and the “Breslau (or Wrocław) Machzor” (Wrocław University Library, Poland Ms. Or. I.1)2 after the cities where they are stored).

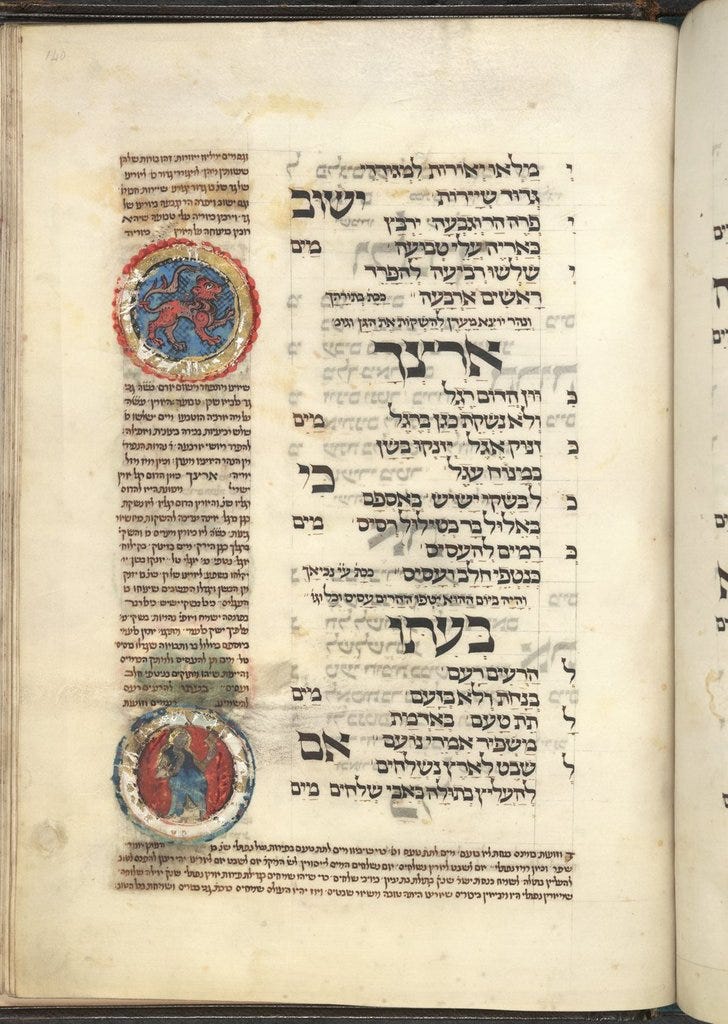

The Leipzig Machzor

Another lavishly decorated (and gold-leaved) Machzor is known as the “Leipzig (or Lipsiae) Mahzor” and was penned by one Menachem, the same scribe noted for writing the Birds’ Head Haggada, which we’ll encounter next week. Here, the human figures are depicted with full faces, wearing characteristic hats that are the subject of scholarly dispute. (Are they historically accurate? Distinctively Jewish? What is the identity of their illustrator?) These same hats appear on the animal-headed humans in the haggada.

The Darmstadt (Hammelburg) Machzor

Completed by Yaakov ben Shneuer in 1348, this machzor, which also contains parts of Rashi’s Talmud commentary, is distinctively and colorfully illustrated. It also records genealogical information.

The Luzzato Machzor

Sold by Southeby’s in 2021 (from the collection of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, formerly Ms. 24), the Luzzato Machzor is named for, yes, Shadal, its erstwhile owner. It’s a pristine machzor for Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur produced in Bavaria, southern Germany, in the late 13th or early 14th century. Unfortunately, its digitization is poor, but you can glimpse just how stunning its illuminations are here. The Luzzato Machzor includes piyutim used in the local custom of southern Germany.

The Rothschild Machzor

Created in Italy in 1490, this machzor (JTS Ms. 8892) extends through Pesach and was illustrated by three different hands, one of which may belong to the scribe, Yoel ben Shimon. I couldn’t find usable images, but you must click over and see some here, or, more fully, here, for serious late medieval Italy vibes.

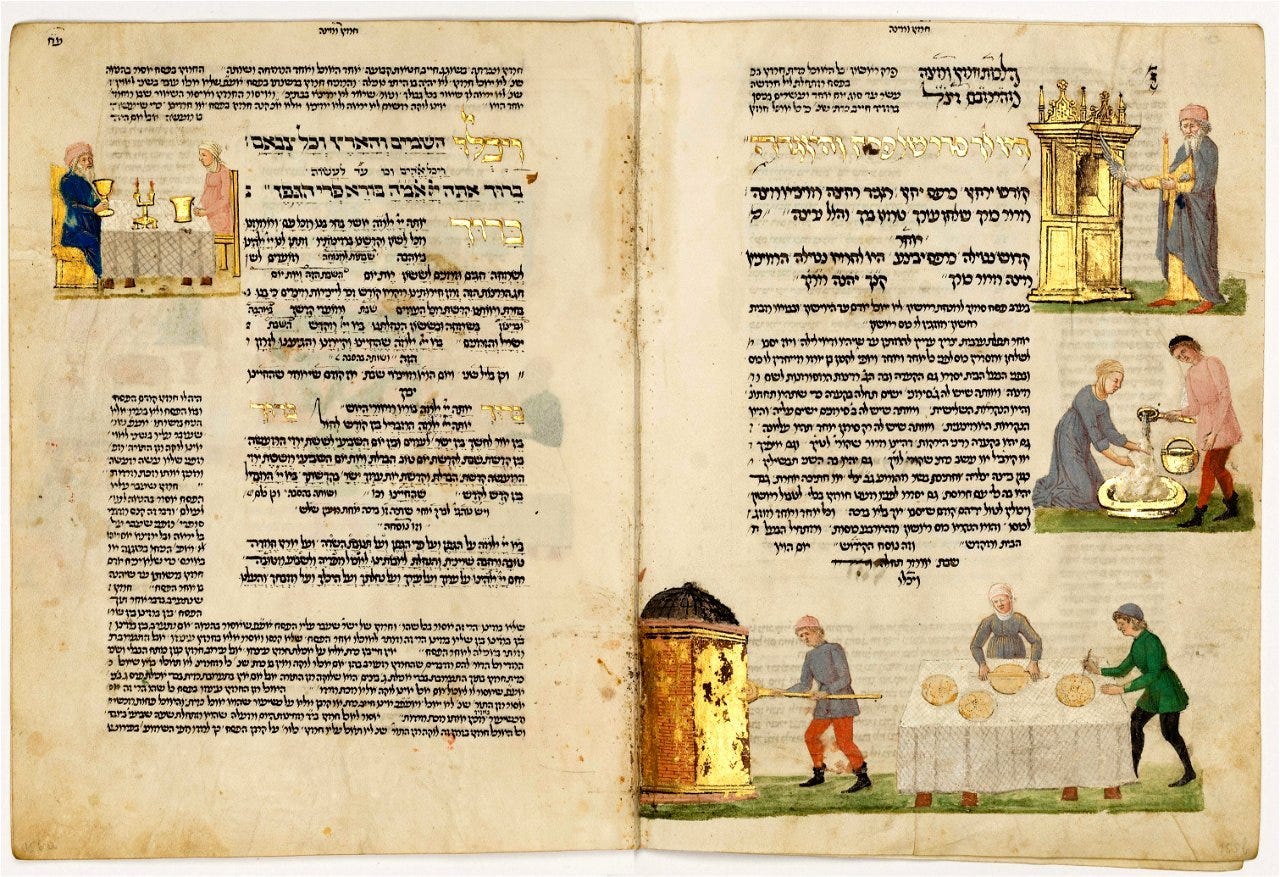

The Rothschild Miscellany

Not to be confused with the Rothschild Machzor, the exquisite Miscellany, which, true to form, includes a scholar’s delight of texts: liturgy, halacha, philosophy, science, history, and literature. It is also ethereally beautiful in its writing, layout, illustrations, and gold-leaf overlays. It was produced in the late medieval period, c. 1460-80, by an unknown scribe.

Reading and Resources on the Early Siddur and Machzor

For more on the British Library’s important copy of Machzor Vitry, see the articles on the library’s website, here and here.

The Amsterdam Machzor has its own website here.

So does the Worms Machzor, here!

There’s a webpage devoted to the Worms Machzor at the National Library of Israel. It also has a wonderful and comprehensive book dedicated to decoding its cultural significance by the noted expert Katrin Kogman-Appel. (It’s pricey but worth a splurge if you’re ever in the market or track it down used.)

The Esslingen Machzor also has a dedicated page at JTS with additional resources, including a link to a fascinating article.

The Saxon State Library has a page devoted to the Leipzig Machzor, and here’s a blog post by an artist about an exhibition of the Leipzig Machzor.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective.