Before History: Avraham Ibn Daud and his Sefer ha-Kabbalah

🌅 Centuries before the practices of modern history emerged, R. Avraham Ibn Daud, a devout Aristotelian rabbinic Jew, wrote us one of the most important records we possess of medieval Jewish history.

You’re reading Stories from Jewish History, a weekly newsletter exploring Jewish thinkers, events, and artifacts, from the famous to the obscure. I hope these stories from the past are providing you with moments of light in these dark times; writing them for you is certainly doing that for me, as do your thoughtful responses. I keep thinking about all the great Jewish thinkers who persevered through the many difficulties of their own times, producing for all masterpieces of Torah knowledge and expanding the canon of Jewish thought. Today, we round out our foray into Muslim Spain with the great, early Aristotelian thinker R. Avraham Ibn Daud, sometimes known as “Raavad I.”

Audio (Paid Feature)

You can find an audio version of today’s newsletter here.

In this issue:

R. Avraham Ibn Daud (c. 1110–1180) began his life as a typical member of the educated classes of al-Andalus. Born in Córdoba, R. Avraham was the grandson of R. Yitzchak ben Baruch Albalia, nasi of Sevilla (Seville), a halachist, court astronomer, and poet who had been the teacher of the Ri Migash. He was taught by his maternal uncle, R. Baruch ben Yitzchak Albalia, a student of the Rif who kept the company of the poets R. Moshe Ibn Ezra and R. Yehuda ha-Levi. His uncle and teacher plied R. Avraham with halacha and Tanach as well as philosophy; so well-read was R. Avraham that he clearly had knowledge of both the Quran and the New Testament.

In the mid-twelfth century, a new Muslim Berber tribe wrested control over a large swath of the Iberian peninsula. Known as al-Muwahhidun (“unifiers,” Romanized as “Almohad”), they, like the al-Murabitun (Almoravids), practiced a strict form of Islam that was intolerant of other interpretations and of minority religious groups. It persecuted minorities and sought their conversion. Along with many other Jews, Ibn Daud fled—to Toledo in Castile, the city with which he is identified.

Writing History Before the Invention of History

Historiographers—scholars who study the history of history-writing—emphasize that premodern chronicles and other historiographical works are to be fundamentally distinguished in method from modern critical history, the roots of which lie in early modernity, perhaps as early as the seventeenth and eighteenth century, but do not blossom and bear fruit until the nineteenth, arguably the twentieth, century. What they mean by this is that the idea of examining a historical topic based on accepted and dispassionate standards of evidence did not really exist in premodernity. This is entirely correct, and yet it doesn’t tell us the full story of humans writing their collective story over the long arch of literate culture.

The fuller story is that people, to varying degrees in different times and places, valued the story of the things that happened to them, even if they approached their presentation and sources in ways unacceptable to modern historians. Instead, they often focused on didactic elements—the values they saw embedded in the stories—or on polemical ones, meant to promote a particular worldview. Such tasks were not seen as inimical to the recording of the past but complimentary, laudatory, and perhaps even morally required. Of course, postmodern theorists point out that, in the end, we modern critical historians are not so different from our forebears, even as we attempt, futility in their assessment, to write objectively and without particularist interest. I think such theorists overstate the similarity, but remind us of the humility we must assume in pursuit of the truth, or as close as we can get to it.

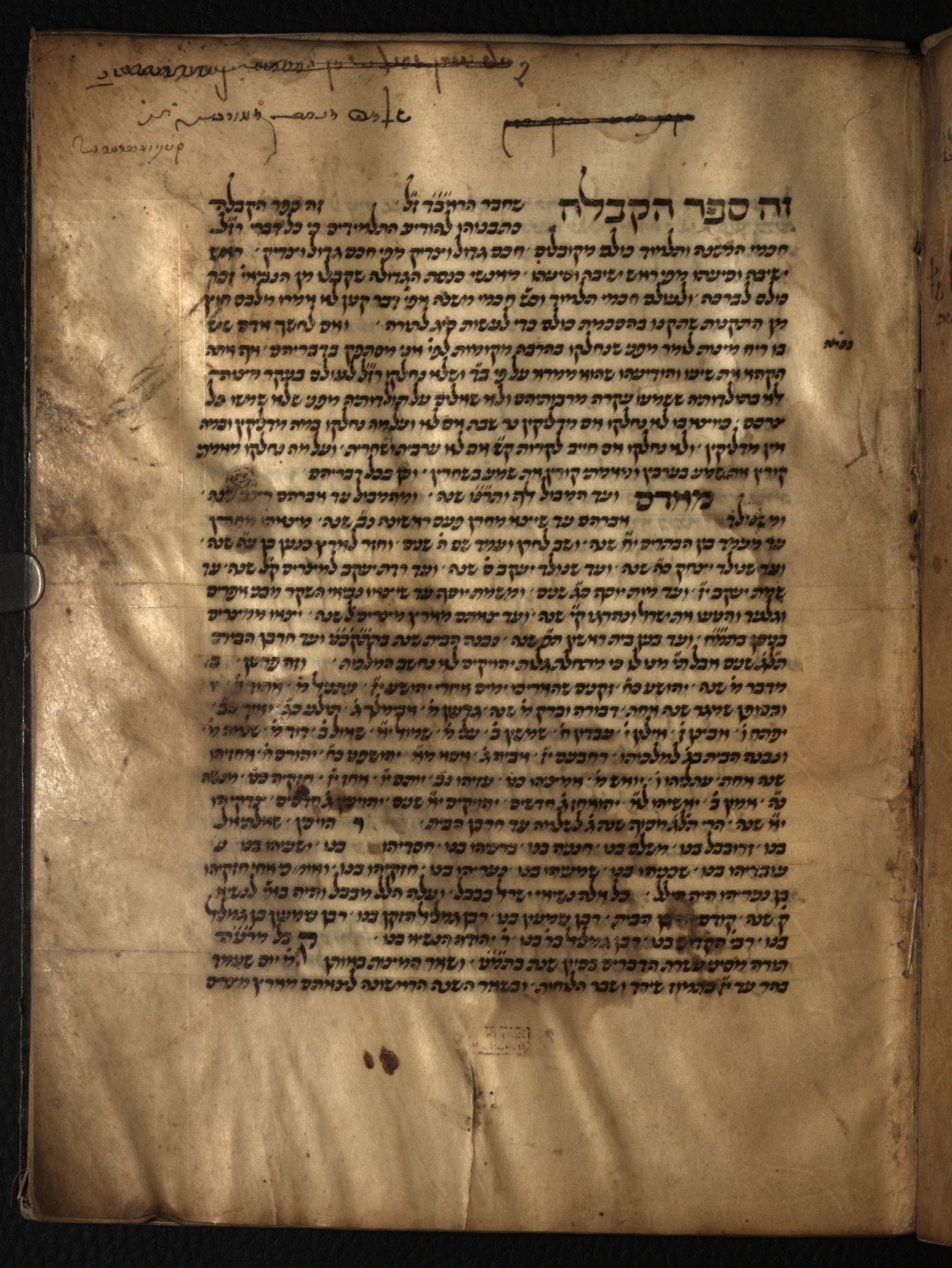

It is with this framing that I want to approach R. Avraham Ibn Daud’s Sefer ha-Kabbalah, or rather the larger, tripartite work of which the first part is best known. Sefer ha-Kabbalah is, to our modern eyes, largely unsourced and at times clearly fabricated, for example, lifting tropes from well-known aggadot of the Talmud Bavli. It is also a masterpiece of premodern historiography that serves as one of our best and only sources for many events, especially those occurring in medieval Spain. In its partial truths, as we would identify them today, it also records kernels we know to reflect historical realities, as well as informing us about the communal-historical beliefs of Jewish elites in twelfth-century Spain.

To see an example of this, let’s look in detail at one of the most important and best-known sections of Sefer ha-Kabbalah, the story of the four captives. (We’ve had occasion to mention this story before, in the newsletter about Rabbenu Chananel.) Ibn Daud begins with the decline of the Geonic academies of Babylonia (Iraq), telling us what is confirmed by many Geonic letters: that the money sent to them from abroad began to dwindle, because the newer centers of Jewish life were flourishing:

ו…היתה סבה מאת יי שנכרת חוקם של ישיבות שהיה הולך אליהם מספרד וארץ המערב ואפריקיא ומצרים וארץ הצבי, וכן היתה הסבה שיצא ממדינת קרטבה שליש ממונה על ציים שמו אבן רמחאץ שלחו מלך ישמעאל בספרד ושמו עבד אלרחמאן אלנאצר. והלך ממונה על ציים אדירים לכבוש ספינות אדום ועיירות הסמוכות לספר. והלכו עד חוף הים של ארץ ישראל ונסבו אל ים יון והאיים שבו

It was brought about by the Lord that the income of the academies [of Babylonia] which used to come from Spain, the land of the Maghreb, Ifriqiya, Egypt, and the Holy Land was discontinued. The following were the circumstances that brought this about. The commander of a fleet, whose name was Ibn Rumahiş, left Cordova, having been sent by the Muslim king of Spain, Abd al-Rahman al-Nasir. This commander of a mighty fleet set out to capture the ships of the Christians and the towns that were close to the coast. They sailed as far as the coast of Palestine and swung about to the Greek sea and the islands therein.

Sefer ha-Kabbala, trans. and ed. Gerson D. Cohen, with slight modifications, Eng p. 63, Heb. p. 46

Notice the details that Ibn Daud is at pains to preserve: the locations of the primary Jewish communities outside of Babylonia, the name of the commander and of the Muslim ruler in Spain, as well as the route of the ship. Both the commander and the king are well-known tenth-century figures. Ibn Daud continues:

ומצאו אניה ובה ארבעה חכמים גדולים היו הולכים ממדינת בארי למדינה נקראת ספסתין. וחכמים אלו להכנסת כלה היו הולכים. וכבש אבן רמחאץ האניה ואסר את החכמים. האחד ר' חושיאל אביו של רבינו חננאל. והאחד ר' משה אביו של ר' חנוך אסרו עם אשתו ועם ר' חנוך בנו ור' חנוך בנו עודנו נער. והשלישי ר' שמריה בר' אלחנן. והרביעי איני יודע שמו…

[Here] they encountered a ship carrying four great scholars, who were travelling from the city of Bari to a city called Sefastin,1 and who were on their way to a Kallah convention. Ibn Rumahis captured the ship and took the sages prisoner. One of them was R. Hushiel, the father of Rabbenu Hananel; another was R. Moses, the father of R. Hanok, who was taken prisoner with his wife and his son, R. Ḥanok (who at the time was but a young lad); the third was R. Shemariah b. R. Elhanan. As for the fourth, I do not know his name…

Sefer ha-Kabbala, trans. and ed. Gerson D. Cohen, Eng pp. 63-64, Heb. p. 46

Here Ibn Daud portrays the Torah center of the tenth-century Mediterranean as southern Italy, the city of Bari, which is confirmed by outside sources as an important and learned Jewish community. As we’ve noted before, Rabbenu Tam says in Sefer ha-Yashar, “They would say of the citizens of Bari, ‘from Bari comes forth Torah and the word of G-d from Otranto’”(בני בארי שהיו קורין עליהם כי מבארי תצא תורה ודבר ה' מאוטרנטו).2 The three named rabbis are also well-attested, and Ibn Daud’s ready admission that he does not know the name of the fourth shows his ability to admit lapses of sources. Ibn Daud continues:

הקדש ושאלה ממנו אם הנטבעים בים חיים בתחיית המתים אם לא. | והוא השיבה אמר יי מבשן אשיב אשיב ממצולות ים. וכששמעה את דבריו השליכה עצמה בים וטבעה ומתה. וחכמים אלו לא הגידו לאדם בעולם מה טיבם ומה חכמתם. והשליש מכר את ר' שמריה באלסכנדריא של מצרים ומשם עלה למצרים והיה לראש. ומכר את ר' חושיאל באפריקיא בחוף הים ומשם עלה למדינת אלקירואן שהיתה בימים ההם חזקה מכל מדינות ישמעאל שבארץ המערב. ושם היה ר' חושיאל לראש ושם הוליד את רבינו חננאל בנו. ובא השליש לקרטבה ומכר שם ר' משה ור' חנוך

These sages did not tell a soul about themselves or their wisdom.3 The commander sold R. Shemariah in Alexandria of Egypt; [R. Shemariah] proceeded to Fustat where he became head [of the academy]. Then he sold R. Hushiel on the coast of Ifriqiya. From there the latter proceeded to the city of Qayrawan, which at that time was the mightiest of all Muslim cities in the land of the Maghreb, where he became the head [of the academy] and where he begot his son Rabbenu Hananel. Then the commander arrived at Cordoba where he sold R. Moses along with R. Hanok.

Sefer ha-Kabbala, trans. and ed. Gerson D. Cohen, with slight modifications, Eng. pp. 64-65, Heb. p. 47

The story continues at some length, focusing on R. Moshe and emphasizing the superior learning of the four captives, with which they seed the new centers of the West. This foundation myth sketches for us a picture with which we are roughly familiar from other sources, but places the facts in a narrative that expresses the sense of the passing of the torch to Spain in particular.

Sefer ha-Kabbala and Yosipon

Sefer ha-Kabbala is the first part of a larger work called Dorot Olam (The Generations of the World). The second part, Zichron Divrei Romi (Annals of the Days of Rome), is a chronicle of the Roman Empire from its founding until the Muslim conquests. It has generally been underutilized in scholarship, particularly its account of the later Roman Empire for which Ibn Daud had fewer sources. It has a strongly anti-Christian polemical bent, seeking to show that the New Testament was a fabrication of Constantine, the Roman emperor who converted to Christianity. The third section, Divrei Malchei Yisrael be-Vayit Sheni (The Time of the Kings of Israel during the Second Temple), deals with an overlapping time period to the second part but from the perspective of Jewish leadership. Like Zichron Divrei Romi, its goal is polemical: it aims to demonstrate that the Tzadokite (Sadducean) heresy was a kind of precursor to Karaism in his own day. Divrei Malchei Yisrael is based heavily on Sefer Yosipon (which I wrote a bit about here), which is the version of Josephus, the first-century Roman Jewish historian, available to premodern Jews; Yospion is a Hebrew paraphrase produced in Greek-speaking Byzantine south Italy in the 10th century.

Because of Ibn Daud’s reliance on Yosipon, his work on antiquity is regarded as less interesting to historians. However, I see in it something remarkable: a sense that the events of the remote past are worth telling and relevant to Ibn Daud’s medieval present. It is not, surely, history in the sense that we use that word today. But our own histories are its descendants, and it can show us the way that the information that we have—even when we must be skeptical of it—was passed down to us.

Ha-Emuna ha-Rama

A early devotee of Aristotelian thought, as mediated through his Arabic commentators, Ibn Daud also wrote a lengthy treatise treating Jewish philosophy. If Sefer ha-Kabbala had the polemical purpose of advocating for rabbinic Judaism, which it sought to achieve through the use of historiography, Ibn Daud’s philosophical magnum opus, generally known in its Hebrew translation as Ha-Emuna ha-Rama (The Exalted Faith), tried to achieve this same aim through rationalism. It has also been called a response to R. Yehuda ha-Levi’s anti-rationalist tendencies and a precursor to Rambam (Maimonides)’s Moreh ha-Nevuchim, by which it was soon eclipsed. Like the Moreh, Ibn Daud’s work sought to reconcile apparent contradictions between Jewish tradition and Aristotelian “science.” It also served as an introduction for the inquiring student to philosophy and how to navigate its sometimes-choppy waters.

Interestingly, while the Judeo-Arabic original remains lost, Ibn Daud’s philosophical treatise was translated twice—both times at the end of the fourteenth century, an exceedingly turbulent time for Sefardi Jews. The years 1391 into 1392 saw ecstatic, mass anti-Jewish riots rip through the peninsula, after which approximately half of the population was no longer Jewish, whether by force, duress, or conviction. (We’ll get deep into this in a later series on the Jews of Christian Spain.) The “New Christians” or “Conversos” included among them many former leaders of the Jewish community. Into this moral, religious, intellectual, and leadership vacuum stepped new voices. One of these was R. Chasdai Crescas, who would become an anti-Christian polemicist and and an anti-Aristotelian philosopher. It was under Crescas’ behest that the first translation of Ibn Daud was made, exactly during the difficult years. It seems that he saw it as a resource for the questions raised by the painful events—even though he would eventually author Or Hashem (in 1410), which departed from Ibn Daud’s philosophical methodology. Slightly later, Rivash (R. Yitzchak bar Sheshet) also promoted its translation, the version of which is titled Ha-Emuna ha-Nisaa (The Exalted Faith). According to modern scholarship, the second translation, which survives in a unique manuscript, is of lesser quality than the first. Regardless, the renewed interest in Ibn Daud’s work by the Jews of Christian Spain during times of duress demonstrates the preciousness of early Jewish philosophical works in providing intellectual responses to despairing seekers.

Reads and Resources

Gerson Cohen’s excellent edition of Sefer ha-Kabbala (the first, main part) is readily available with Hebrew text, English translation, notes, a thorough introduction, and extensive supplementary materials. The remaining sections as well as the Midrash on Zecharia are published with analysis by (my friend) Katja Vehlow, but it’s a Brill book, meaning it’s quite pricey. An older edition (Hebrew only) is available online here.

The Jerusalem, 1967 edition of Ha-Emuna ha-Rama is available on HebrewBooks.org.

Gerson Cohen’s article on the story of the four captives (published in PAAJR in 1960) is available here.

This newsletter is, and will remain, free to all. If you enjoy it and would like to support my work, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive full access to the newsletter archive, audio versions of each newsletter, exclusive eBook versions of each series, and a special monthly issue of the newsletter focused on the cycle of Jewish holidays in historical perspective. If you’d prefer to make a one-time donation in any amount, you can do that easily through my page at Ko-fi. Thank you so much.

This city has not been definitively identified.

Teshuvot section, siman 46.

I.e., knowing that this would make them more valuable and therefore more expensive to redeem. (My heart breaks all over again writing this.)

You made my day!

It's not so hard to do that; anyone who declares that they've read and care about Ibn's Daud's book The Exalted Faith will do the same. (But unfortunately there aren't many of us out there.) And I don't even need to completely identify with your approach to Ibn Daud: I come from a slightly more traditionalist approach that looks at his historical book, Sefer Hakabala, less critically.

And great background about Zichron Divrei Romi, and why The Exalted Faith was translated when it was. Never knew that.

I want to add to this conversation the critical contribution of The Exalted Faith to Jewish thought.

The Rambam (Maimonides) wrote prolifically about the fundamentals and philosophy of Jewish thought in two styles: 1. In his Commentary and Code he used plain language meant for the wider public, with deeper nuances that advanced scholars can read "between the lines". 2. In his Guide he assumes that his audience knows all of Torah thought and law, is proficient in Aristotelian philosophy, and got confused between the two, and his solution lies in contemplating some of mankind's deepest and most subtle concepts. Throughout the Guide he warns repeatedly that he is not writing for a general audience.

So there's a gap in his writings: there's awesome middle and high school material, there's awesome post-grad material, but there's no equivalent of the college level. And most of us aren't going to be studying the lengthy tomes of Ibn Sina, Alfarabi, and Aristotles that the Rambam recommends to begin with. We won't learn from the Rambam in a simple, basic way, how philosophical principles integrate with the Jewish faith.

The Exalted Faith is one of the few books that fill in this gap, and is by far the most thorough and in line with the Rambam's school of thought. (Ruach Chen and Kuzari are the only two others I'm aware of that to any degree join this genre.) This book methodically goes through Aristotles' main principles and explains the Torah's perspective on them, and then, based on that synthesis, suggests 6 principles of the Jewish faith, which apparently were the basis for the Rambam's 13.

My teacher has told me that the Rambam's worldview was certainly partially formed by The Exalted Faith.

Long live The Exalted Faith!